By Phil Jarratt

I don’t mean the 11 world titles or the multi-million sponsorships. I mean how does greatest of all time surfer Kelly Slater keep popping up around the globe through this pandemic, catching incredible waves, often almost alone?

Being based in Trump’s America, where you can travel almost anywhere, helps, as does the fact that he qualifies for a working visa as a pro surfer, but Kelly has always been a bit of a phantom – a bit like MP without the five-paper spliffs – but this year he seems to have worked his way around border closures and health advisories to pop up all over the place at the right time.

It all began in mid-March when we were both headed for the same place, the WSL Piha Open in New Zealand, when it was cancelled 48 hours before the window began. At the time there was good surf on both coasts of the North Island, but Kelly was up north playing golf. Then a couple of days later, he turned up at an East Coast break and wowed a bunch of groms with a frenetic session of punts, before signing autographs on the beach.

Next, he flew into Sydney – on legitimate compassionate grounds, to see a dying friend – and caught some of the best autumn swells while holed up in Avalon. From there, he was in Hawaii, California and, if I’m not mistaken, even home in Florida briefly, before the next round of KS sightings began, this time in Bali, where his two-up in the barrel session at Padang Padang with Rizal Tanjung and other local buddies became a social media sensation a couple of weeks ago, and he also scored some nice Keramas with the Wozz.

This week a Bali-based mate flicked me a photo on WhatsApp simply tagged, “KS G-Land yesterday”. So now the GOAT is in Java, safe in the eastern jungle while the pandemic rips through the north and west of the most populous island of the archipelago, looking relaxed enough about it as he banks off the bottom and sets up for the run through Speedies. It could have been a one-day helicopter hit mission from the Bukit, of course. That’s how he rolls.

We’ll probably never know.

Points turn it on at home

Not that we have anything to complain about here in Noosa. Until the northerly devil wind kicked in this week in time for the school holidays, we’d had a great run of fun waves on the points, with even sand-screwed First Point weighing in with some great sessions out wide with only light crowds.

Despite my relatively new role as a cub reporter for this august organ of record, I was making time to score a few myself until I popped a rotator cuff which has taken away my fun tickets for a while.

There were some great waves at different times on all of the points, but the sessions I enjoyed the best were at First Point with Josh Constable and family having fun, the former world champ leading the way with some graceful glides on his ten-footer.

Farewell Murph the Surf

Of all the crims who one way or another became “legends” in our strange small world of surfing, none got quite up my nose like Jack Roland Murphy, the Floridian jewel thief and convicted murderer known in Miami and Cocoa Beach as Murph the Surf.

I found this particularly galling because it sometimes caused confusion, not only with Rick Griffin’s cartoon character, but with my late friend Francois Lartigau, the artist and French surfing champion also known as Murph. The fake Murph died of natural causes in the US a week or so ago at age 81, having spent about a third of his life behind bars, a third masquerading as a television evangelist and about five minutes as a real surfer.

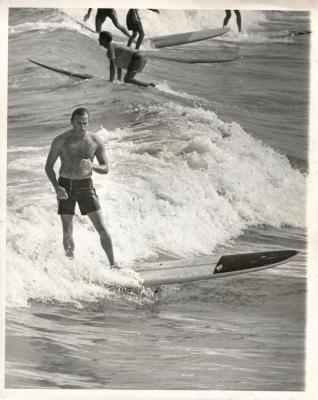

Jack Murphy emerged from the Florida swamp during the early ‘60s surf boom, and won a couple of minor surf comps at Cocoa Beach – a decade before Kelly Slater was born there – before hitting the headlines for the first time in 1964, when, according to his obituary in the New York Times, the “tanned, roguish, party-loving beach boy from Miami transfixed the nation by pulling off the biggest jewel heist in New York City history — the celebrated snatching of the Star of India, a sapphire larger than a golf ball, and a haul of other gems from the American Museum of Natural History.”

Murphy and his accomplices left a trail of amateurish clues to the museum theft and were caught by New York detectives two days after the crime, although the loot — worth more than $3 million in today’s dollars — was still missing, stashed by then in waterproof pouches in Miami’s Biscayne Bay. They did time for the heist, but by 1967, Murph was on the surf beat again, showing up at trade shows and briefly opening a surf shop. But in that year he also took two female accomplices out for a speedboat ride, beat them to death and threw their bodies overboard, attached to concrete blocks.

Murph went inside again, emerging only in 1986 as a happy clapper thrilling daytime TV audiences in the Deep South.

“For much of his adult life, Mr Murphy was a caricature drawn from the publicity that engulfed him,” the New York Times eulogised. “Even the mainstream press portrayed him as a kind of folk hero,” the NYT concluded, doing exactly that.

In 1996, Murphy was inducted into the East Coast Surfing Hall of Fame.