By Phil Jarratt

If you’ve been to Noosa Main Beach or Little Cove over the past 18 months – and is there anyone who hasn’t? – you may have wondered where all the sand came from and how long it will stay.

Anecdotally, many old Noosa hands and veteran surfers have been claiming that this is the most sand seen on Main Beach in decades. Scientifically, Noosa Today can reveal that a new study shows that this is the most sand we’ve seen in at least 60 years. But if wide sandy beaches are your thing, you’d better love it while it’s here, because the study also predicts that future wave climates are likely to make this occurrence less frequent, with more erosive wave periods resulting in narrower beaches on average.

The research, titled “Influence of wave direction sequencing and regional climate drivers on sediment headland bypassing”, published last week in the Geomorphology Journal, is the work of University of Sunshine Coast PhD student and researcher Daniel Wishaw and USC’s Professor Javier Leon, assisted by Helen Fairweather and Allen Crampton.

The research team analysed 60 years of aerial imagery to identify periods of erosion and sand accumulation on beaches around Noosa Headland, comparing beach widths with known wave, tidal and ENSO phase (El Nino and La Nina) data to understand why erosion and accretion occurred, and assessed how projected future changes in the wave climate (less swell from the south east and more from the east) would influence these beaches.

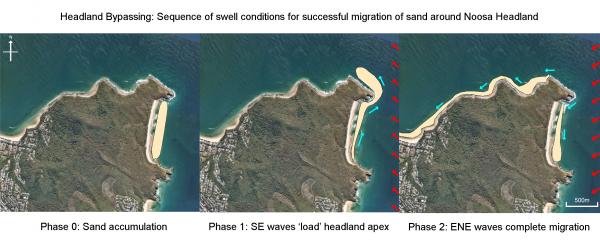

Noosa Main Beach is fed by sand that moves around the headland from Alexandria Bay, and that movement of sand is caused by two kinds of ocean swell events that occur only rarely, but happened twice in quick succession in 2019, leading to a larger than normal amount of sand being transported and migrating on to Noosa Main Beach.

The USC researchers say that for this much sand to move around the headland a specific sequence of waves was required. First, a swell event of more than 2.5 metres from the south east was required to push sand to the headland apex, before a similar event from the east or north east pushed this sand into the bays on the north of the headland (Granite, Tea Tree, Little Cove) and eventually on to Noosa Main Beach. The result is the greatest volume of sand on Main Beach and the widest strip of beach seen at any time over the 60 years covered by the study.

Putting the amount of sand currently on Main Beach in some kind of perspective, researcher Daniel Wishaw says: “The Noosa Council survey team provided survey data of Main Beach that indicated that it naturally loses approximately 10,000 cubic metres of sand per year on average, with the sand recycling system that the council operates working well to balance these losses. But with the sand more or less setting up camp on Main Beach, there has been no need for sand pumping for well over a year. Between winter 2019 and winter 2020 we accumulated 41,000 cubic metres. It seems pretty evident that this rate has continued through to the current time, but I don’t have any survey to back it up. However you could reasonably extrapolate that to being around 60,000 cubic metres now.”

While the white sands of Main Beach have been a real plus for the Covid-led boom in domestic tourism over the past six months or so, the sand build-up has been a mixed blessing for surfers. First Point hasn’t broken properly for more than a year, while Little Cove and the outer bays have produced endless days of barrelling surf during quite minor swell events. With one popular break out of the equation, crowds have been more intense at the other points.

Long-time local surfers still talk about a similar, although much less significant, sand migration during the La Nina phase of 2010, when sand deposited in Laguna Bay off First Point actually moved the surf break from the point into the bay, before things returned to normal after a couple of months. The intensity of the current sand migration makes it much harder to move, although that will happen soon, according to climate change projections.

Says Daniel Wishaw: “For First Point, the sand has really built up there because we have had two relatively quiet summers with respect to wave activity, which would usually push that sand through the system. The combination of having a big 2019 and a quiet 2020 and 2021 so far, means we have had a big build-up, with a lot of backlog still to be cleared from Little Cove. Effectively, that’s sand in the bank for Main Beach, so it’s going to take a considerable and prolonged swell event, or a couple of them in a row, to flush the sand out of First Point and make a difference.”

Daniel’s estimate is that a three to four metre east swell over a period of five to seven days is needed to normalise Main Beach. While the Easter bunny is predicted to bring us a two-metre east swell this weekend, it is unlikely to make a difference.

The USC study predicts that in coming years the extension of the tropical zone will mean more erosion events than accretion, requiring greater sand management to stabilise the beach. So, if you’re a sand-lubber or a sandcastle builder, make hay while the sun shines. If you’re a First Point surfer, be patient. Our time is coming soon.