Lawyer, academic, historian, land rights activist, advocate for social reform, provocateur … Noel Pearson, now 55, has worn many hats over his illustrious and frequently controversial career. Perhaps the one that fits him best now is philosopher, and he can be seen wearing it as he walks or kayaks along the Noosa River, not far from his home outside Tewantin, lost in his many thoughts.

Pearson keeps a low profile in his adopted community, preferring the anonymity of his family’s neighbourhood bubble after more than 30 years as an often-divisive figure at the forefront of Indigenous reforms. “I’m a FIFO fixer these days,” he chuckles. “Fly in, fly out, get home to my bubble.”

He grew up on the Lutheran Aboriginal Mission at Hope Vale on Cape York, became the first of his extended family to graduate with double degrees (history and law) from university and became the “poster child” for the Aboriginal land rights movement in the early 1990s. But it was his branching out into the even more provocative issues of social welfare reform in Aboriginal communities that made him a national figure in the new century, lionised and criticised in about equal measure by his people and by the media.

Pearson has his detractors, but not even his fiercest critics can deny the power of his ideas and his delivery of them. Through his voluminous writings and the magnificent oratory of “The Light On The Hill”, his Ben Chifley Memorial speech in 2000, and his eulogy for Gough Whitlam in 2014, he has become the most passionate and eloquent voice for social justice, black or white, since Charles Perkins.

In this two-part interview with Phil Jarratt, the cancer survivor reflects on a life full of challenge, opportunity and continued hope.

What did you learn from your mum and dad, growing up in Hope Vale?

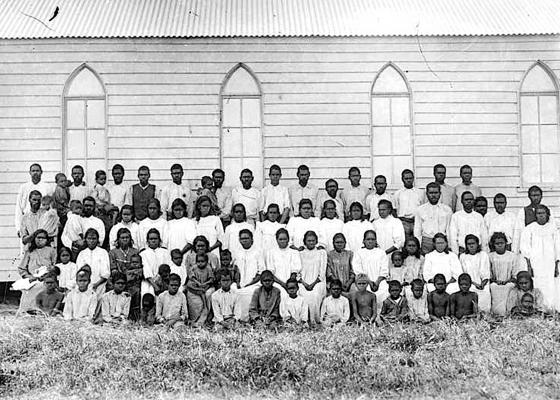

My father grew up there as his father did, after being brought in as a child. My grandmother was brought in by the police as part of the removals policy, born in the bush and then taken to the mission. So I grew up as a Guugu Yimidhirr person, but also as a Lutheran, heavily influenced by the missionaries. The missionary allowed our language to be taught and the culture to be maintained, but he didn’t allow us to practice our traditional religion. It remained our unofficial religion, but it wasn’t part of formal mission life.

How did the young people feel about being denied that part of your culture?

Well, I later went to Sydney University and wrote a thesis about that. People of my generation were critical of mission history, whereas my father and grandfather who had grown up in it could see the truth of it, which is that if the missionaries had not come in at that point in our history, we would have been wiped out, literally. We were on the frontier. Cooktown was a frontier town, the Palmer River gold rush brought 60,000 people, thousands upon thousands of Chinese, opium, massacres … In 1886, 13 years after the white people arrived in Cooktown, the missionaries found us and they found a wreckage. The tribes of the district were pretty much wasted, and the missionaries set up a refuge from the frontier.

My grandfather was 10 years old when he was brought to the mission, stripped away from his parents who were still walking around wild in the bush. My father used to tell me he’d see my great-grandfather – his grandfather – still walking around in the bush, hunting and living the nomadic life, increasingly being squeezed by the pastoral and mining takeover of the land. My father would see him when he came and hung around the edges of the mission. The wild blackfellas, as the missionaries called them, weren’t allowed inside, so he’d give my father whatever he’d caught, wallaby or pig, and then go.

Pre-war there were still a lot of people in the bush on Cape York, and a few in other places. But if there were children in those camps, the police were onto them immediately, so increasingly the camps were just groups of old people, and you can imagine how lonely that was. One of my most vivid memories that I construct when I go to the old camps near Hope Vale, is of the last days of that life, with no children, no future, knowing that when they died out, that life would die with them. They would have been the saddest days. In 1942, when the mission was moved to Woorabinda near Rockhampton during the war, almost a third of them died of influenza in the cooler climate.

Why were they moved?

The Australian Army believed that if there was a Japanese invasion the Torres Strait Islanders and the Aborigines would turn against the Australians because they’d been so ill-treated. The policy was to move Aboriginal missions down south or into the interior. The German missionary from Hope Vale, Mr Muni our people called him, Georg H. Schwarz was his name, was interned in Toowoomba for the war.

When you were a young bloke being brought up by the Lutherans, a Lutheran had just become the premier of Queensland. Did Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s rise to power have any impact on the Lutheran missions?

His history with us preceded his political career. He actually helped relocate the mission back to Hope Vale in 1949. Our people were like the children of Israel – we’d been in exile in a strange land and we needed to go back to our homeland, to the promised land. That was the way the elders saw it, in a religious context. But the problem was to get the land back, and this was where Joh played a pivotal role. He flew over it, surveyed it, then organised the money to purchase the land and helped set up the process of re-establishing the mission on it. He was chairman of the Hope Valley Mission Board for 10 years until the late 1950s, when he got into Country Party politics. Our people had fond memories of Joh as a churchman who had supported us.

Was Bjelke-Petersen a formative influence on you?

On my generation, yes, because the church was such a big part of our lives, but running alongside of it was this growing resentment of the paternalism, and the church never really learnt to stop being paternalistic. They didn’t realise that times were changing, and the way they related to our people needed to change. My father couldn’t leave the mission without getting the permission of the superintendent, he couldn’t own a car. When he worked as a drover, his money was managed by the state, and was stolen by the state. All the money that our people made was put into a big fund, whatever money they earned was not theirs, it was held by the state.

This was happening before my time, but the big eye-opener for me was when I went to high school in Brisbane. The church opened up high school access before the state, and from 1964 some Hope Vale kids were able to go to boarding school at St Peter’s Lutheran College. My father’s generation was only allowed to go to school to grade three, then they had to start working at 14. When I went to St Peter’s it was the first time I’d been in the white man’s world. My whole life to that point had been at a remote mission where the only white people were the ones running the place. I’d never known racism, although I had a sense of it when I went into Cooktown as a child, just watching the interaction between our people and white people. We had a certain place in their little town.

If you walked past the old Sovereign Hotel in Cooktown you wouldn’t hear words like that?

Well, we wouldn’t do that! (Laughs). We had our place. We arrived on the back of the mission truck, we’d go up to the hospital for check-ups, we’d go to the caf¨¦ and then go and sit in the park. We had a strict routine and where we could go was very limited. So my awareness of racism was very dim until high school, and then I was exposed to it not just within the school but outside as well. The other day I was with my son in Brisbane and we drove past Brisbane Boys College, and I told him I played rugby there, and I’ve never forgotten it. It was a Wednesday afternoon and half the school was on the sidelines calling us abos. Our whole backline was made up of PNG and Aboriginal kids. But we gave as good as we got, and if you were good at sport, you survived. I was good at rugby, basketball and athletics, so I survived. In fact I loved it.

Why did you go to Sydney University?

To get out of jail. To escape what was now the National Party. Joh was now ascendant, and he had cottoned onto the fact that kicking the blackfellas wasn’t a bad move politically. That tore me up, knowing the good he’d done for us through the mission, but I realised that he had to be viewed from two angles. There was Joh the right-wing politician and Joh the dutiful churchman. To be honest I was stunned every time I came across media reports of Joh casting aspersions on Aboriginal people or land rights. It pained me that “our church friend”, as we used to call him, got mileage out of doing that.

Did you ever get the opportunity to confront him about it?

No, I didn’t, but many years later I was told that Joh had said how disappointed he was in me for being ungrateful for the opportunity he’d given me. (Laughs) But we forget that in the early ‘80s, Brisbane was still a big country town, very insular, so I decided to go to Sydney to study.

Were you inspired to write your 1986 thesis about the history of Hope Vale Mission by bad memories or good?

I was even-handed in my treatment. I could see both sides, and my father and grandfather would never have let me get away with just focusing on the bad. By and large, they would agree with my criticisms, and the main one is that the Lutherans should have changed with the times. I was around at the time when they resisted change, and when they were forced out, and I thought that we had thrown the baby out with the bath water, that we didn’t work out how to keep the good things the missionaries had given us and discard the bad things. The mission had set us up strongly as a community, and had the doors of opportunity been opened at that point, we would have been in a much better place now. I’m part of the generation that benefited. I had strong parents who set me up well. The generation that came along next had too much welfare, too much family breakdown.

Did your generation have an advantage in the isolation that has now turned into a disadvantage?

That’s part of it, yes. One of the strengths of the mission was its isolation, away from the bad influences that would eventually corrupt the social fabric of the community. Isolation had been a factor for 120 years. It was the way the missionary stopped the exploitation of our people, stopped the opium, the prostitution, the exploitation of labour.

For my thesis I had to do a lot of oral history interviews, and I was able to catch the old guys of my grandfather’s generation just before they died, the last of the bush-born people. And from that, I developed a sense of what had gone before, and that helped me consider the future.

NEXT WEEK: Noel Pearson sees the light on the hill.