“Humans have a morbid fear of being eaten alive. People are afraid but how dangerous are sharks really?” This was how Professor David Schoeman summed up the dilemma faced by marine experts and conservation group members who attended the Noosa Biosphere Reserve Foundation’s Marine Species Protection Symposium at Sunshine Beach Surf Club on Tuesday.

The symposium followed the release of the 2019 report, Queensland Shark Control Program: A Review of Alternative Approaches and plans by the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries to trial alternate shark control measures across the state.

Noosa Surf Life Saving Club president Ross Fisher told the symposium it was the job of Noosa’s well trained, well-equipped volunteer lifesavers to protect and educate the public and save lives.

The last fatal shark attack occurred at Noosa Main Beach in December 1961 when a 22-year-old surfer was taken by a bull shark. Shark nets were installed in 1962 and there hasn’t been a fatal attack since. “Would I like the nets removed – no,” he said. “If they come up with a safe alternative – absolutely.”

NBRF director Greg Schumann said a local solution was sought that protected beachgoers but minimised impacts on non-target species, including dolphins, turtles, whales, stingrays, dugongs and threatened shark species that fall prey to the nets.

Tourism Noosa Head of Sustainability Juanita Bloomfield told participants Noosa was visited annually by 2.46 million people delivering $1.18 billion to our economy and 84 per cent of arrivals came to Noosa for the beach. “We’re one of the most popular tourist towns in Australia,” she said.

In an international survey of 500 travellers 40 per cent of respondents said they had heard of shark attacks in Australia and 14 per cent said they would not travel to Australia because of shark attacks.

Noosa Main Beach has two 180m long, 8m deep shark nets located about 80-90m from shore and three drumlines.

Action for Dolphins CEO Hannah Tait aims to raise awareness of the high killing rate of untargeted species by shark nets and promote the use of non-lethal shark deterrents.

“Noosa wants to be seen to be protecting this wildlife,” she said.

Since 2001 there have been more than 670 marine animals captured in Main Beach shark nets and drum lines, including three whales, two dugongs, more than 30 dolphins, 120 rays as well as turtles, she said.

Lawrence Chlebeck from the Humane Society International said sharks were the species most impacted by the nets that killed 83 per cent of animals caught and drumlines that killed about 70 per cent caught, but not all shark species caught were dangerous to humans and some were threatened or critically endangered.

He said a number of NSW Councils had stopped using shark nets in favour of smart drumlines.

The devices alert the drumline contractor when a baited hook is taken giving them about 30 minutes to release them.

Lawrence said during a trial of the smart drumlines there were 716 animals caught, 70 per cent of which were target sharks, with less than 1per cent killed, due to a rapid response and the use of large circle hooks.

Flinders University Associate Professor Charlie Huveneers who has studied shark bite mitigation measures for the past decade said there was a plethora of alternate shark control measures available with none 100 per cent foolproof.

Charlie put forward three methods of reducing the incidence and severity of shark bite. These involved reducing the interaction between sharks and humans with measures such as enclosures and early warning systems, using personal deterrents to reduce the likelihood of shark bite and using specially made swimwear to reduce the severity of shark bite.

Having scientifically tested personal deterrents he said only electrical-based deterrents proved to have some ability to deter sharks.

Tests on a specially made shark bite resistant neoprene material has shown it to have some effect on reducing the depth and size of shark bites but has not been tested on all species of shark, he said.

USC geographer Dr Javier Leon said more and more research had used drones to study sharks. Easily accessible and relatively inexpensive drones can keep a watch on sharks and alert swimmers to their presence through an alarm system.

He said it was reasonably easy to establish a logarithm to detect a species such as a shark and drones were already being trialled to monitor sharks.

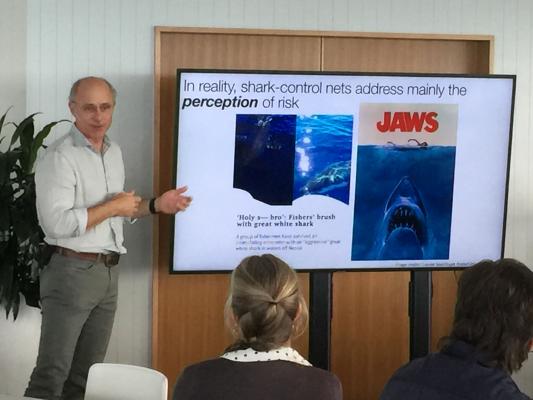

Dr David Schoeman questioned the real risk to humans of shark attack comparing the risk of death by shark bite to other causes of death.

In any year 56 per cent of people die from heart disease, cancer, respiratory disease or diabetes and 200 die a year from drowning. More people die falling out of bed or from excessive heat. In the past year five people died from dog bite and three from shark bite.

“As many people get eaten by dogs as by sharks but we don’t fear getting eaten by dogs,” he said.

“The problem is perceived risk. We need to convince people sharks are not out there to kill them.”

David described the death of animals in shark nets which drown “slowly and horribly” as “an inhumane catch”.

“We have to have a strong rationale for doing it,” he said.

Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Shark Control Program research and policy coordinator Dr Tracey Scott-Holland told the symposium the government was progressing with an education program, Shark smart, aimed at curbing risky human behaviour and planned to trail smart drumlines in Central Queensland in the middle of the year.

Tracey said much research had been conducted in the Whitsundays monitoring shark behaviour and movements.

She said a drone trial had been launched in September 2020 in partnership with SLSC. During the trial 54 sharks were sighted and followed until they left swimming areas with beaches closed on four occasions.

She said the department planned to work in partnership with SLSC to trail the Shark smart education program.

Greg Schumann said local shark control options put forward during the symposium would be included in a report to be forwarded to the department for consideration.