When you write a history of the relatively small town you live in, as I have just done, it is inevitable, no matter how much research you do, that something or someone will slip through the cracks.

In the couple of months since the completion of Place Of Shadows, several such small failings have been pointed out, but the epic fail I can’t forgive myself for is that I didn’t fully appreciate the importance of the creative legacy of the Monks family. Eight generations of this pioneer family have come into the world since John Monks migrated from England in the 1850s, and six of them have built their lives around Gympie and Noosa.

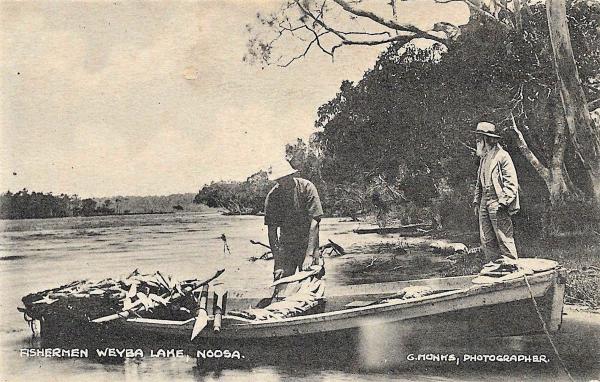

There are a surprising number of pioneer families who are still active in Noosa, but even by their standards, the Monks lineage is impressive, and few families have left their stamp so comprehensively across generations. The key figure in this is the photographer John George (JG) Monks who documented Noosa from the late years of the 19th century through to the middle years of the 20th, from lantern slides to impressive black and white film prints, but whose work over time has been disguised through much of it being credited to Griffith Studios and other agencies.

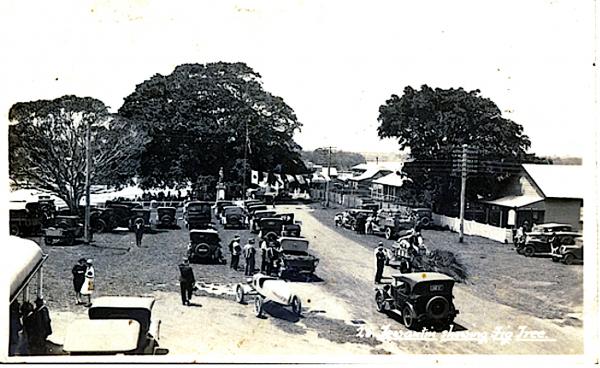

In fact JG, known as George, was present at every triumph, celebration, fire or flood that shaped the Noosa story over more than 50 years, and many of his pictures, such as the breast-plated portrait of King Tommy outside the Royal Mail Hotel, or the automobiles lined up for the opening of the TM Burke road and bridges linking the river towns in 1929, have become iconic Noosa images.

Now, sisters Jeniffer Petty and Sharyn Rieger, granddaughters of JG Monks, daughters of historian Colin Monks, and descendants of triple-great uncle John Monks, are working to preserve JG’s photographic legacy and, through it, tell the family story, and what a story it is.

While Jeniffer has been working on techniques to produce high quality scans from the rapidly deteriorating magic lantern slides, Sharyn has been researching the family tree and all the attendant documents.

She says: “My research tells me that John Monks, my great-great-great grand-uncle, born in England in 1822, was actually in this part of the world before the Gympie goldrush began, making him one of the very earliest settlers. When the goldrush started he was one of the first to get up there, and he did quite well with his North Smithfield claim, although it almost claimed his life when the horse securing him to his whim bucket was spooked by a passing circus elephant, leaving him dangling above the mine shaft for some time before being rescued by his goldminer mates.”

By 1870 John Monks had built a home in Gympie, squatted on a large water frontage on Weyba Creek (not far from where the Monks Bridge crosses it today) and paid for the passage of two nephews, George and Walter, who came out from England to help him on the properties. Although he didn’t officially get title to the Weyba land until 1901 (paying just under 40 quid for 319 acres), from 1880 John and his brood built a substantial 12-room homestead and adjacent cabin which was rented to visiting fishermen. On a cleared part of the acreage, the Monks established an extensive market garden and an orchard with enough grape vines to keep them in white wine.

John Monks seemed to enjoy every minute of his long and busy life, dying in 1914 at the ripe old age of 92.

Sharyn Rieger writes: “His obituary, along with our family stories, paint him as an adventurous spirit and larger than life colourful character, sporting a long white beard, teaching and playing the violin and piano accordion for everyone’s enjoyment, and to add a bit of humour to the long trips back and forth to Noosa, where he pushed his wheelbarrow to Gympie, loaded with salted and smoked Lake Weyba fish, to sell to the goldfield prospectors.”

The ‘wheeling a barrow full of fish to Gympie’ story is also part of the folklore of Joe Keyser and his sons, neighbours and fishing buddies of John Monks, and the Monks girls hold it to be true. This writer is sceptical but, short of filling a barrow with fish and attempting to wheel it along Walter Hay’s overgrown “shortcut” track to prove a point, he will accept its veracity.

Sharyn continues: “[Uncle John] also had a curious mathematical and scientific mind, and a keen interest in the natural world, pouring over a bank of biological slide specimens which his British relatives shipped over to him, along with a then-state of the art microscope that we still have today. When the Weyba Homestead was established and guests started arriving, he and the family would hold ‘movie nights’ projecting these natural specimens and lantern slide photographs, (later taken by George and John George Monks), onto the walls of the homestead, using the family’s ‘Magic Lantern’, which we also still have today.”

Although his son JG would become the star photographer of the family, George Monks was a keen chronicler of the natural environment and also brought with him from England the family tradition of painting, signwriting and decorating.

Says Jeniffer: “John George was a great photographer, and all the men through the generations were good signwriters, so I think our generation of girls inherited an artistic streak. Sharyn is very creative and I’ve studied art. There’s something in our lineage pushing us into creative pursuits.”

Although JG worked hard at the family signwriting business in Noosa and Gympie, he couldn’t disguise the fact that photography was his passion and where his true talent lay.

Writes Sharyn: “John George used to take his cameras and bee light meter on many trips around Noosa, capturing the land and seascapes of the area. No doubt the family affinity with the land and aesthetic appreciation was in his genes, as he developed an early passion for capturing light in his photography, aided by the latest photographic equipment shipped over from the Monks relatives in England. He became Noosa’s earliest photographer and from a young age seemed to have an eye for composition. While he probably didn’t realise it at the time, the many photographs he took during his lifetime have stood the test of time, preserving special moments of Noosa’s social and environmental history.

“JG’s photographs are now housed in the John Oxley Library in Brisbane, the Monks photographic collection, and on the Noosa Heritage Website. His photography arguably became a vehicle for opening up the beauty of Noosa to others in those early times. I find it fascinating, and an honour to JG, to see that so many Noosa locals still have the same passion for capturing the early and evening light of the Noosa landscape and how much everyone still appreciates the beauty of it with their photographs today.”

John George Monks died in 1960, before Sharyn was born, but Jeniffer remembers her grandfather as being very busy with the two threads of his career and a bit aloof with children.

“He was a man’s man who loved a beer and a day at the races, but he was also a good father. Our dad adored him, to the extent that when JG died our father kept the ‘Monks & Son’ signs on the business premises at our then-home at Munna Point and at Gympie for many years.”

Although he was a good student with an enquiring mind, JG’s son Colin Monks left school early to go into the family business. Writes Sharyn: “My father’s final ‘test’ as an apprentice to his father, was to paint the perfectly proportioned letters on the roof of Laguna House, a huge task back then without any templates or scaffolding.”

Then the war intervened. Stationed on Bougainville with the Australian army, Colin was approached by his sergeant to do something about the alarming number of Americans who were drowning in the surf.

“You’re from Noosa,” the sergeant said, “Surely you can teach them about the waves.” So Col Monks started a surf club patrol from scratch, improvising belt, reel and everything else.

After the war Col married Jessie (known as Millie) Tebutt from Gympie and began a family. Says Jeniffer: “Dad always put family first, he worked very hard to provide for us. He’d work from early morning until late at night, making his own paints. He was loving but a strict disciplinarian. I always remember him in relation to his love of the water. He’d shuck oysters and I would eat them, over and over again.”

Sharyn: “He was passionate about Noosa and worked hard to preserve it. He wrote a 500-page submission to save Weyba from development. Because of his war service he was also passionate about the Tewantin-Noosa RSL where he worked as a welfare officer and became a life member.”

Colin Monks published a colourful and entertaining local history called “Noosa: the way it was, the way it is now” in 2000. He died in 2015, just a month short of his 90th birthday.