Fifty years ago this week a surf movie premiered at the Manly Silver Screen in Sydney that would change a lot of young lives, this writer’s included.

Morning Of The Earth was the debut feature for director Albert Falzon and producer David Elfick, who had raised funds for the production through the success of Tracks magazine, which they part-owned and for which I was a regular contributor.

I attended the premiere a couple of days before moving to Canberra to take up a position in the Sydney Morning Herald’s political bureau. With Gough Whitlam leading Labor on a charge towards power, and promising to end conscription for National Service (my own Army deferment for journalism studies would expire at the end of the year), I was excited about the move to the political vortex, less so about the fact that I would be two hours inland from the nearest surf break.

Morning Of The Earth drifted dreamily from one surfing nirvana to the next without narration or explanation, powered by an original Oz rock soundtrack, but a 15-minute sequence towards the end, set in a little-known speck on the Indonesian archipelago, proved to be a game-changer for me and most of my generation of surfers. I remember replaying the Bali sequence in my head as I drove to Canberra, although it would take me almost two years to get there.

In August 1969, the Ngurah Rai International Airport had opened on a narrow isthmus of land just south of Kuta on the island of Bali, opening it up to direct international flights for the first time. One of the first surfers to fly in was Russell Hughes, an Australian champion who had placed third in the world championships in Puerto Rico just nine months earlier.

After the world titles he had apparently made his way to Europe and then Kabul, Afghanistan, which had become the major supply source of hashish oil. Whether he was carrying a trafficable quantity of the drug when he landed in Bali on the way home will never be known, but Hughes, who died in Canada in 2011, always lived the high life despite often having no visible means of support.

When he got home to Australia, he was happy to share the knowledge that there was good surf in Bali, but he became evasive and annoyed when pressed for more detail, clearly planning a return to his new secret spots. Soon the surfing bush telegraph was sending out a cryptic message from Russell Hughes that something was going on in Bali.

Only the cool could break the code, and the home of surf cool at the time was the Whale Beach house, at the far end of Sydney’s northern beaches peninsula, where the surfing magazine Tracks began publication in October 1970.

Tracks was the brainchild of architecture student and surfer John Witzig, surf photographer and designer Albert Falzon, and music entrepreneur David Elfick. In rough tabloid newspaper format, Tracks railed against pollution, apartheid and the Establishment, and championed pot, sex and soul surfing. It was an instant hit, providing Falzon and Elfick with a platform to raise enough money to produce a surf movie that similarly broke new ground.

After having shot late summer and early autumn on the north coast of New South Wales and Queensland’s Gold Coast, in May 1971 Falzon watched a rough edit and felt his movie lacked a wow factor. At the end of the year he would have to take the mandatory trip to Hawaii for the big wave finish, but some kind of exotic side trip would be the icing on the cake.

Elfick came up with an idea. Although he was not a surfer, he had spoken to Russell Hughes about his adventures in Bali. Elfick secured a contra airline tickets deal and presented the case to Falzon.

Elfick had scammed enough tickets for them to take their girlfriends, but since there were possibly no surfers in Bali, they needed to take talent. Falzon saw special qualities in a 14-year-old kid from Narrabeen named Stephen Cooney, an exceptionally talented surfer who could portray a loveable little boy one moment and streetwise bad boy surfer the next. Since they were going into the great unknown, Elfick felt the film needed a father figure to guide young Cooney.

It just so happened that former United States surfing champion, craggy-faced Rusty Miller, was living in Byron Bay and driving down to Sydney for a week a month to sell advertising in Tracks. Miller was only 28 at the time, but he’d had a wealth of surfing experience in all kinds of waves, and he was a thinker who sometimes smoked a pipe to underline his gravitas. He was the perfect old man of the sea.

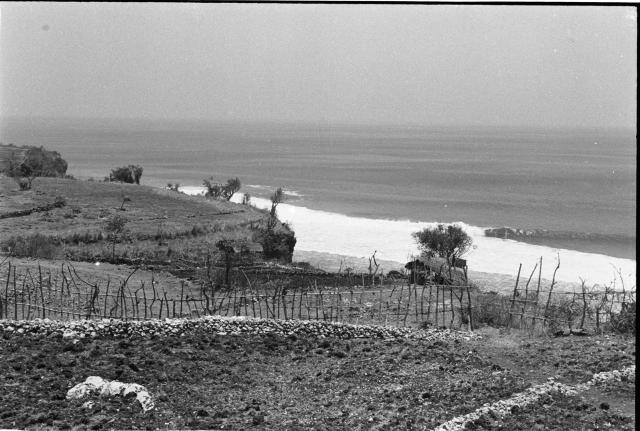

When the surf at Kuta went flat, Falzon and girlfriend Tanya Binning took a bemo (small bus) to the dusty Bukit Peninsula to search for waves. They were dropped at Pura Luhur Uluwatu, one of the island’s most sacred temples, and slowly worked their way along the cliffs, more than 50 metres above the ocean. It was a long, difficult and exhausting hike in the heat of the day, but eventually Falzon saw what he’d been looking for.

Two days later on a rising swell Miller and Cooney watched carefully for some time before easing themselves down into the access cave. The tide was low and the surf was huge. With no leashes to secure them to their boards (a luxury whose time had not yet come), Miller and Cooney, man and boy, stood on the platform of reef and waited for the waves crashing beyond them to subside so that they could paddle out.

Shooting from a low angle, Falzon saw an image of profound beauty that would stay with him forever, as it would with so many who saw the film. The two silhouetted figures were bathed in an eerie yellow light as the surf crashed around them in this remote and dangerous place. It was an image that captured at once the excitement and the trepidation of surf exploration, and in the minds of the pioneer surf explorers, it was an image that would be forever Bali.

Planet Surf was about to undergo a seismic shift with the release of the landmark film the following year. Falzon adapted his title from the 1950 Jawaharlal Nehru description of Bali as the morning of the world. The film-makers took as their philosophical positioning statement a quote by underground film guru Jonas Mekas: “We are the measure of all things, and the beauty of our creation, of our art, is proportional to the beauty of ourselves, of our souls”.

Thousands of surfers wrote it down or memorised it as they left the cinemas and made their way to travel agencies to book their tickets to surfing’s new frontier. I know. I was one of them.

To celebrate the film’s 50th anniversary, Morning of the Earth has been meticulously restored and beautifully remastered from the original 16mm rolls over three years by Santa Barbara surfers and film-makers Wyatt Daily and Justin Misch. Each of the 150,000 frames was digitised in 4K and underwent a museum-grade digital restoration process. To match the original projection, the film was colour-graded, stabilised, de-flickered, all while staying true to the director’s original vision and the 16mm source format. The soundtrack was also remastered for a completely revamped experience. According to Albert Falzon, “It looks and sounds better than it ever has”.

The remastered Morning Of The Earth will screen at The J, Noosa Junction at 6pm on Friday 11 March as part of the Noosa Festival of Surfing. Tickets at noosafestivalofsurfing.com