There was a sea of smiling faces in the lobby of the Sunshine Coast Conference Centre at Twin Waters last Monday as almost 1100 delegates arrived from all over the country for Australia’s biggest Indigenous conference.

Although some Covid safeguards were still in play, as the mob gathered there was a palpable sense of relief, that after two years of being hampered by lockdowns and remote attendances, the annual summit of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies could proceed face to face.

And no one was more excited than the Kabi Kabi representatives, hosting Indigenous Australia’s biggest gathering for the first time on country.

Founded in 1964 as the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, AIATSIS has come a long way over nearly 60 years, now tasked with telling the stories of First Nations, creating opportunities for people to encounter, engage and be transformed by that story and creating a cultural resurgence from its Canberra base. While the week-long AIATSIS Summit is open to all, it is dominated by First Nations delegates (more than 700) who make up more than half of the presenters and speakers during five days of presentations and workshops.

The theme for the 2022 Summit is “navigating the spaces in between”, which according to the notes “foregrounds the brilliance and value of Indigenous ways of knowing, seeing and being in the world, [providing] the opportunity to bring things from the periphery into focus, recognising that in these spaces in between there are opportunities for innovation, but also risks and complexity… It suggests a focus on a journey and destination but also requires us to reflect on where we have come from”.

AIATSIS chief executive officer Craig Ritchie found a more interesting way to express this concept in his opening address to the Summit.

An Aboriginal man of the Dhunghutti and Biripi nations, his career path has encompassed a Churchill Fellowship researching Indigenous leadership models around the world, and policy and reform roles at the highest levels of the public service, but he chose to illustrate his point by recalling a conversation with an elder.

“I like to tell the story about a conversation I had with Kaurna elder Lewis O’Brien about the way people look at things, and we talked about the way our old people look at the sky and the stars and see things that most of us don’t see. Uncle Lewis told me, ‘We can see those things because we look at the spaces in between.’ I found that revolutionary, because it means we shouldn’t just be interested in the objects we see but how they interact with each other, how they relate to each other.”

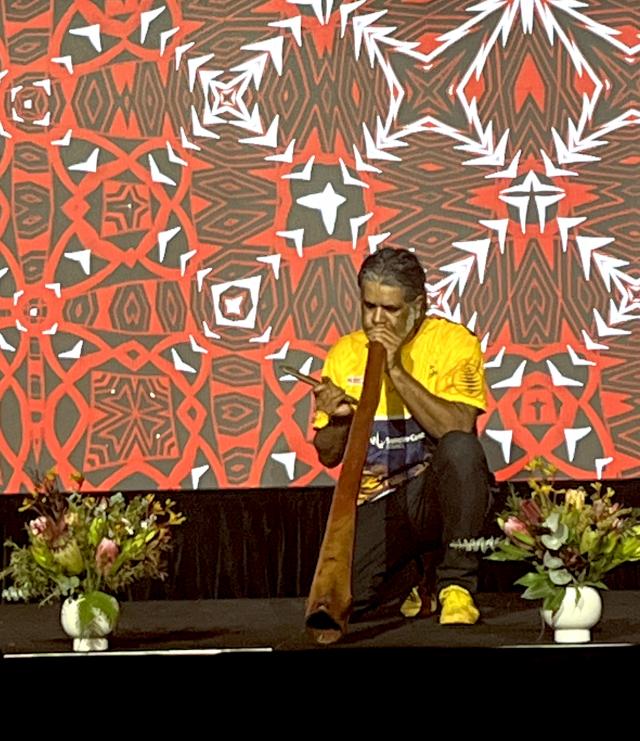

The CEO couldn’t have found a better representative of navigating “the spaces in between” than Kabi Kabi artist and musician Lyndon Davis, whose humorous but deeply-layered presentation of his Beeyali Project, collaborating with University of the Sunshine Coast, had the large audience enthralled.

Beeyali is a Kabi Kabi word meaning ‘to call’, and the work visualises the calls of wildlife on Kabi Kabi country using cymatics, the science of visualising acoustic energy or sound. It’s a big idea involving experimentation using new technologies and different environmental materials to reveal cymatic images.

For Floating Land 2021, held last October on Lake Cootharaba, a projection and sound work was developed where sonic vibrations become ripples and energy, creating dynamic geometric patterns, using digital photography.

Each sound has an individual pattern, and the wildlife featured, including cockatoos, lorikeets and even passing whales, have a unique geometric visualisation of their call, a sonic fingerprint. This project provides new ways to connect to the environment and discover connections between scientific methods, Indigenous knowledge and new technology. Basically, turning sound into art.

If the above sounds complex, it was not.

It was spellbinding, and a Beeyali Project exhibition, Djagan Yaman, is currently on at USC until 6 August.

It was left to Kabi Kabi Native Title claimant Aunty Helena Gulash to close out the opening session.

She reminded delegates that for the Kabi Kabi it had been a very long road to Native Title, starting with the exile of generations of families, her own included, to Cherbourg, but the end was now in sight.

The sky was dark and gloomy as I walked to my car, but I left the first session of the AIATSIS Summit with a lightness of spirit and hope in my heart.

Yes, it’s just another talkfest, but it seemed like a lot of people here were seeking solutions, and knew where to find them.