The publication of a fascinating book and the opening of an accompanying exhibition of dolls at Noosa Regional Gallery next month puts a new focus on a little-known piece of Noosa history, and on the relationships between European settlers and First Nations peoples 150 years ago.

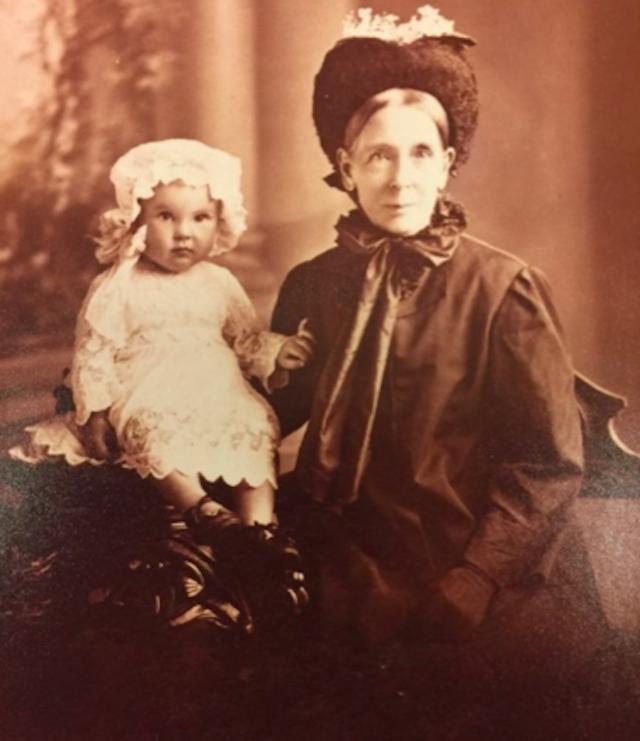

The link is through the remarkable English-born Sarah Ellen Midgley, who in the early 1870s emigrated with her family as an eight-year-old to live at the primitive Mill Point timber settlement on the shores of Noosa’s Lake Cootharaba, befriended Aboriginal playmates and later turned the experience into a book and built a successful cottage industry out of making dolls in their likeness.

I first became aware of Sarah Midgley and her Bungeree dolls two years ago when I interviewed leading Queensland historian Dr Ray Kerkhove, then a historian-in-residence at Noosa Library.

“Before we had swagman dolls we had Aboriginal dolls, and I found in my research that they were created by Sarah Midgley whose family, the Barons, moved to Noosa when her father started working at the sawmill at Mill Point,” Ray said.

“Her two Aboriginal playmates, Widgeon and Kummera, had such a profound effect on the young girl that more than half a century later, as a successful Brisbane businesswoman, she began making dolls in their image, and was soon selling them to doll collectors around the world.

“She modelled her dolls from characters in her book, which was apparently unpublished but I was able to find in manuscript form in the John Oxley Library, and Tewantin elder King Billy was one of them.

“It gives us a real window into the interaction between Indigenous people and the settlers.

“Are they offensive today?

“Not from the research I’ve done with the Kabi Kabi. In fact, the key people are quite excited about the historical matches between the dolls and real people.”

Now, a collaboration between Kerkhove, Noosa Council Heritage coordinator Jane Harding, freelance writer Louise Martin-Chew, and the Noosa Regional Gallery, supported by funding from the Noosa Council Heritage Levy and the Regional Arts Development Fund has resulted in the first publishing of Midgley’s story, Picanninie’s Yabba Yabba, with illustrations by local artist Annelise Howes, and accompanied by an essay by Kerkhove contextualising the story and Midgley’s dolls, and discussing the historical significance of both.

Jane Harding explains in her editor’s note to the new book: “On my first reading of the manuscript, I was captivated by the descriptions of the emigrant voyage and early days in Noosa – 1873 was the dawn of European settlement in the district – and delighted by the [Enid] Blyton-esque tone.

“However, the work includes language and attitudes that are outdated and racist and which may cause offense to readers.”

While this may be true for some readers, from my reading of parts of the manuscript, I found the tone quaint and a little cloying when the author, then a middle-aged woman, attempts to sound like the young girl she was when she met Widgeon and Kummera, but far more important in my view is the insight the text gives us into the settler experience and of the sometimes-difficult interaction between Europeans and First Nations.

And, as Harding points out, the Traditional Owners have been engaged by the project team and have expressed their support.

A couple of months back in these pages, in an article called Truth Telling, I lamented the fact that while parts of the settler story in Noosa were well-documented, we know virtually nothing about the reaction of Kabi Kabi elders like King Billy, who became well known to Sarah Midgley during the few years she spent in Noosa, or about the realities of master-servant relationships.

Well, courtesy of Harding, Kerkhove and their team, and of course, of Sarah Ellen Midgley, we do now.

As Harding writes in her note: “History is full of amazing, unique and interesting stories as well as ‘messy bits’, of which we are often less proud in hindsight.

“This story has both. And both are important if we are to learn from the past and work towards not repeating things that we now see as ‘mistakes’.”

Perhaps the trick is to look beyond the historic racism inherent in the author’s (Nell in the book) first encounters with the Traditional Owners to the more tolerant and lasting relationship that grows from them.

For example, this is Nell’s account of first contact with King Billy and future playmates Kummera and Widgeon at Mill Point.

“The old gin grinned and said, ‘Me Noora’. As though this were a signal of some sort, all the blacks then chimed in and tried to tell their names. There was a terrible noise. All the dogs began to bark, and there were cries of, ‘Me King Billy’; ‘Me Kummera’; ‘Me Widgeon’. But at last, when the noise was becoming almost unbearable, a tall thin black fellow [who said his name was Captain Wish], was pointing to another black fellow, who also wore a brass plate, but a very dirty one, and saying as he pointed: ‘That fella King Billy.’ King Billy was little, and fat and dirty, and the kiddies giggled when they heard his name. He looked a funny sort of king to them. Then Captain Wish pointed to a thin little gin and said, ‘That girl belongit me – name Widgeon; other girl called Kummera.’”

The story of the adult Sarah Ellen Midgley is almost as interesting as her childhood introduction to Noosa’s frontier life. During his stint as a timber-cutter, Sarah’s father Charles Baron, a former civil servant in England, found enough gold on the Gympie digs to send his daughters to boarding school in Brisbane. Mostly, however, he was broke and binge-drinking, and eventually deserted his family to return to England.

But stoic mum Sarah Baron established a successful restaurant on Adelaide Street near Parliament House, where daughter Sarah, now working as a seamstress, also did dinner shifts as a waitress.

Here she met clergyman, poet and Queensland politician Alfred Midgley, who dined at the Baron family restaurant frequently while his dying wife was hospitalised. Despite a big age difference, Alfred and Sarah married a few months after the death of his wife.

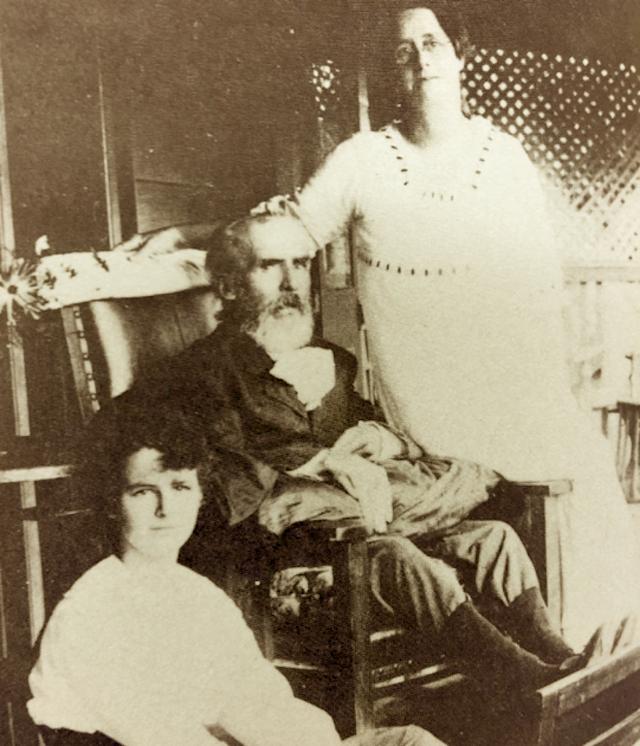

Although they enjoyed a brief time in the Brisbane social spotlight, by the early years of the new century, Alfred’s career and health were declining at about the same rate.

Alfred lingered for another 30 years, but Sarah Midgley, way ahead of her time, became focused on creating her own legacy, which eventually led to her founding Corinda Knitting Mills, manufacturing baby clothing. And at some point as her business expanded, she started to think of those simpler times, when she had just arrived in Noosa and met the most extraordinary natives.

The Budgeree dolls were invented to celebrate those memories.

The exhibition launch will be on Friday 15 July and it will be open to the public at Noosa Regional Gallery from Saturday 16 July to Sunday September 4, 2022. The book will be on sale at the Gallery.