Of all the many questions about careers on the line arising from the Rip Curl Pro Bells Beach – which is ongoing at the time of writing – the perennial but now deadly serious doozey of them all is, what do we do with Kelly now?

The greatest of all time began the Australian leg of the world tour at Bells last week desperately needing a result following a shaky start to the season in Hawaii and Portugal or face the ignominy of being dumped from the world tour he dominated for decades at the mid-year cut. Hovering right at the cut line, Slater really needed a quarter final finish or better at both Bells and Margaret River, the last even before the cut.

With a shaky forecast right through Easter, the WSL called the event on in pretty ordinary conditions at Winki Pop on day three of the waiting period, but the surf improved through the day and, coming on at the end of the round against world number one Jack Robinson and hungry local wildcard Xavier Huxtable, Kelly actually had the benefit of some nice long walls to work with. He looked the goods, even taking to the air, and came last, which is what happens when, at 51, you’re more than twice the age of either of your heat rivals.

Relegated to the elimination round in big onshore Bells bowl on Easter Sunday, the veteran again produced some solid rides to win the heat and progress to the round of 32 later in the day, where a rampaging Kanoa Igarashi, equally desperate to get above the cut line, ended Kelly’s Bells campaign.

If you choose to tread where no surfer has gone before, to surf on the world stage well into middle age, at least a decade longer than any other pro, you’ve got to learn to take defeat on the chin, even when you have 11 world titles and 54 event victories over 31 years on tour behind you.

And Kelly did, but there was an unmistakeable air of sadness, perhaps even confusion, in his post-heat interview. Asked about the seeming certainty of being cut after Margarets, he said: “It sucks.”

Swellnet’s Steve Shearer probably summed up feelings about Kelly’s impending retirement best.

“We’ve taken it for granted for so long and now that we are right on the cusp of the candle going out we treasure it [a competitive appearance] like a rare and fragile bird. Miracles have been known to happen, of course – the empty tomb being the most famous and timely example – but there was no resurrection miracle for Kelly Slater today.”

Assuming that the GOAT doesn’t pull off a miracle by winning at Margaret River (which I think puts him over the cut line, dependent on final Bells’ results, but is realistically not achievable) the question is, what does he do now?

The sensible, appropriate and dignified thing to do would be to take a leaf out of Owen Wright’s playbook and pull up stumps now, call Margies your swansong and then have an encore wildcard in your own wave machine at the Surf Ranch Pro next month.

But Kelly didn’t get this far into a truly remarkable career by following anyone else’s playbook, and he still clings to the idea that he can represent his country at the 2024 Olympics before slinking off into the sunset.

Ain’t gonna happen. Fortunately, because I still love to watch him surf, we haven’t seen the last of Kelly Slater, but we have seen the end of his pro surfing career.

A full rundown of the Bells comp and its implications for several of our surfers in this space next week.

Vale Yunupingu

Changing the subject, in the 1980s I spent a lot of time in the Northern Territory as The Bulletin magazine’s roving bush correspondent.

The idea behind my appointment was to update the magazine’s profile from its original cover slogan of Australia for the white man (1890s, admittedly), so a high priority was recognising Aboriginal stories as of national interest.

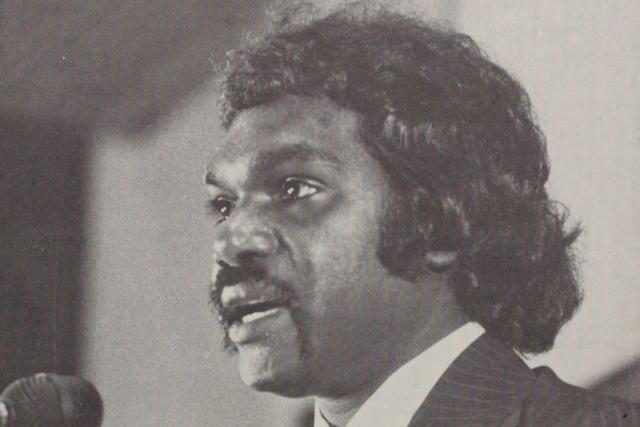

In this capacity I visited remote communities and met many interesting First Nations elders and land rights pioneers, but only moved from acquaintance to friend with one, the revered Yunupingu, who died after a long illness on 3 April.

I first met Yunupingu (and I struggle with the appropriate usage, because to me he will always be remembered by another name) at a conference in Darwin soon after he had been elected as chairman of the Northern Land Council.

The 1978 Australian of the Year was already a land rights’ hero and a celebrity, but on country he was just an ordinary good bloke, so he invited me to visit his family on the Gove Peninsula.

A few months later we visited the new family compound at Ski Beach on Gumatj tribal land on Melville Bay, and later I stayed there twice, learning about the Yolngu people, how to spear fish in the shallows, and drink beer in the late afternoons looking out over the peaceful waters.

We were both young men then, and despite our obvious cultural differences, we found common ground.

Now I’m old and he is gone, a hero not just to First Nations but hopefully to all Australians, never to be forgotten.