It was a golden years romance, and it blossomed in, of all places, the Brisbane office of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Allan and Shirley Williamson had each left a failed first marriage, and found companionship, and later love, in a shared passion for nature and bushwalking, joining the Queensland Naturalists Club and spending weekends exploring the bushlands around the city.

For Allan, that was second nature.

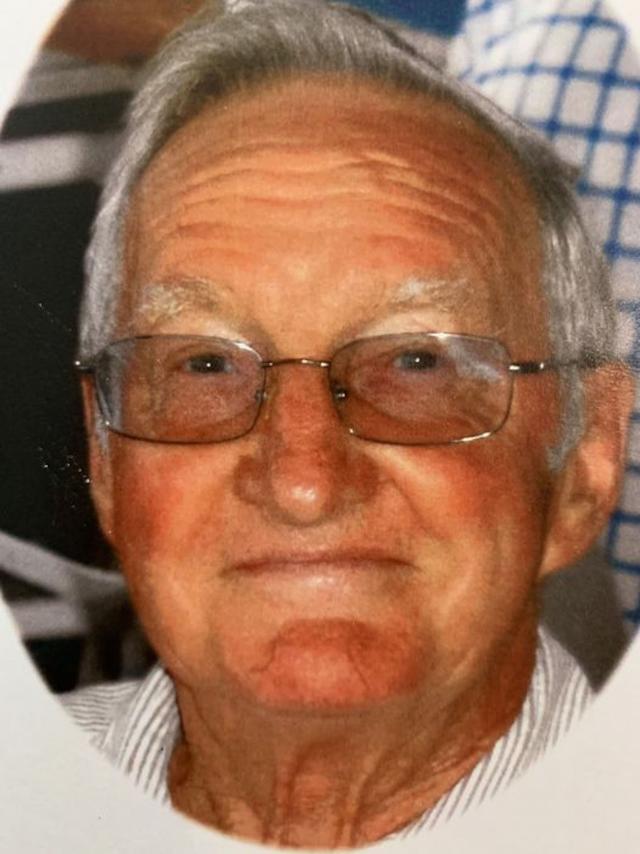

Born in Christchurch, New Zealand in 1930, he started his working life as a trainee in the New Zealand Forest Service before taking a management course and progressing to administrative roles in the medical and other industries.

After being transferred to Australia by the company he was working for, he took a job in the public service and moved to Brisbane with his then-wife.

Born in England, Shirley did a bilingual secretarial course at the French Institute in London before marrying early to a geologist and migrating to Canada for his work.

“Unfortunately not to the French part,” she quips.

Following a midlife career change and a PhD in Japanese history, her husband was offered an academic position at the new Griffith University in Brisbane, so they migrated again.

After working for a doctor while her marriage crumbled, Shirley joined the public service, where she met Allan.

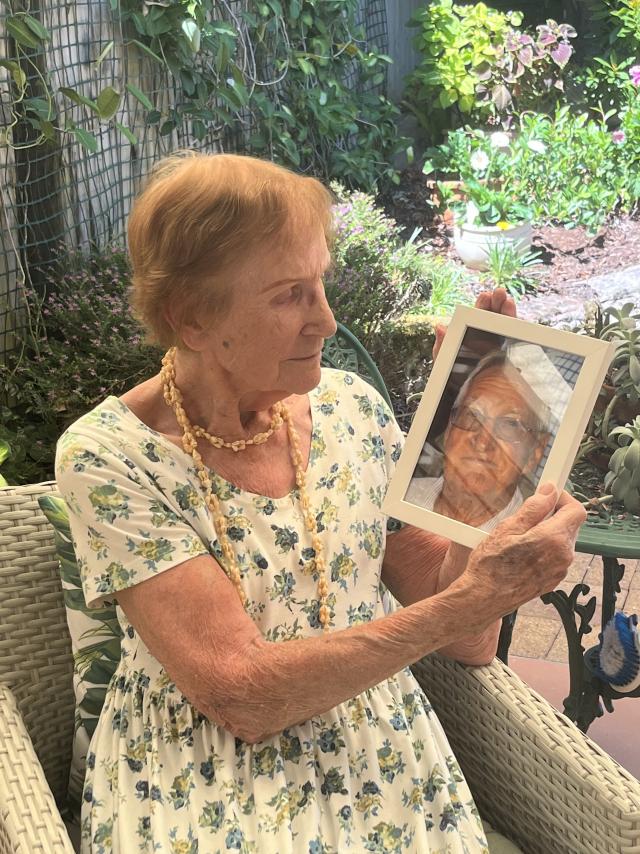

“We never married, you know,” the delicate but sharp-witted 89-year-old tells me as we sit in the garden terrace of her Tewantin retirement home residence.

“I just started calling myself Mrs Williamson for convenience here in the village.”

The Williamsons made the move to Noosa 28 years ago, after some time together in Brisbane. “We were 61 and 65 at the time, both newly-retired, and Allan was a very forward-thinking person, so it was his idea to buy in a retirement village so we wouldn’t have to make another move. We looked around Brisbane and the Gold Coast, then at Hibiscus at Buderim but they didn’t have anything available and pointed us to Hibiscus Noosa Outlook. And it suited us perfectly.”

Allan and Shirley embraced the Noosa outdoors lifestyle with gusto.

She recalls: “We both loved bushwalking and found our niche here. Allan organised a couple of bushwalking groups and took part in various other activities, including publishing a little guide book, and, as I had been secretary of the Toohey Forest Protection Society in Brisbane, when we joined Noosa Parks Association soon after arriving I was invited to join the management committee.

“We loved discovering new walking trails around Noosa and sharing them with the walking groups. Allan was very good at remembering where he’d been and finding that place again.

“Allan was always adamant that we should do the things we wanted to do while we were able, so there were a lot of holidays, we saw a lot of Australia and New Zealand and, of course, our bushwalking around Noosa was wonderful.

“We used to love going out to Devil’s Kitchen in the Headland park, or walking up Shepperson’s Hill at Kin Kin, or around the bottom of Lake Weyba from Murdering Creek Road. I feel we really made the most of our time.”

The Williamsons ate wisely and well and exercised every day. They were the poster children for seniors living, but just a few years into this idyllic lifestyle, Allan’s health started to fall apart.

As Shirley begins to document Allan’s litany of ailments for me, I pause her and ask if she really feels up to discussing the nitty gritty.

She smiles sweetly and says: “We were always upfront with these things between the two of us, so I can be the same with you. In fact, it’s helpful to talk about it.

“Allan was plagued with quite a few illnesses. It started in 1998 when he got colon cancer, then later stomach cancer, prostate cancer, bladder cancer, and also heart problems. He had three bypasses, a stent and a valve implant.

“And he was a diabetic and he got an infected foot and had to have his big and second toe amputated. It took a long time to heal and he had to have a foot pump to drain the fluid. It was amazing he was still alive.”

With Allan’s problems starting to consume their daily life – because of his toe amputations he had no balance, and when he fell Shirley didn’t have the strength to get him back up – the Williamsons reluctantly made the decision a year ago to admit him to Noosacare Kabara, a residential aged care facility in Cooroy.

Later in the year Allan underwent another of the regular cystoscopies he had been having since 2012 to control his bladder cancer. Afterwards the urologist told the couple that he could do no more, that Allan’s life was coming to an end.

With the practised air of someone who has spent much of a working life making bosses appear smarter than they are, Shirley excuses herself and returns a minute later with a handwritten timeline of the last chapter of her partner’s life.

Following the urologist’s advice, Allan had been in palliative care at Kabara since the beginning of the year.

Says Shirley: “He’d been through an awful lot by this time, including having a tube put through his back to drain his kidney, so he had catheters and tubes all over him. He couldn’t move without two people assisting.

“On 12 January someone from the palliative treatment team came to see how he was doing. Allan told him he wanted to die, and the gentleman was able to tell him about the new Queensland legislation for voluntary assisted dying, which had become law on 1 January.

“We’d seen programs on TV about people going to Switzerland or elsewhere to die, and we both thought that would be a possibility if you couldn’t do it in Australia.

“When he told me his decision in January I was very supportive because I didn’t want to see him suffer any more. I knew I’d be sad to lose him but I was also happy that he had the option to go this way.

“The Voluntary Assisted Dying team was contacted and the process began with their first interview on 24 January. You have to validate that you have less than 12 months of life expectancy, you have to be over 18 and you have to say you want this and understand it completely at three different times in front of witnesses. Allan never wavered.”

There was a slight issue over whether Allan’s various serious conditions qualified him as terminal, but the testimony of the urologist resolved that.

Allan and Shirley chose injection over a lethal drink, and the date was set for 2 March, just five weeks after first contact with the VAD team.

On the Monday before the VAD, 27 February, Allan’s daughter Karen decided he should have a last meal, like someone being executed.

She arranged for a mobile catering company with two chefs to come to Kabara to create a slap-up lunch.

Says Shirley: “They produced a white linen table cloth and napkins, silver service and menus. Allan had requested Hervey Bay scallops, hot apple pies from McDonalds and a cheese and berry platter. Allan didn’t like wine so we toasted with beer and the chefs served us in their white jackets.

“We sat out on the terrace looking at the trees along Cooroy Mountain Road. We could have been at a resort anywhere. It was wonderful.”

On the early morning of 2 March, Dr Susan Redman, one of the presiding doctors who was well aware of Allan’s love of bushwalking, collected leaves and banksia flowers while walking her dog. These were later scattered around the room while Shirley’s flowers were placed to either side of the bed.

Her daughter had put some of Allan’s favourite music on her laptop. While Vivaldi’s Four Seasons filled the room, Shirley sat at his side and held his hand while the VAD injections were administered.

Allan Williamson’s pain was over.

“What do I feel now? Shirley asks rhetorically.

“Relief, mostly.

Relief that we’ve made things better for Allan, but also, in a strange way, better for me because having to see someone you love go downhill like that is not pleasant. Knowing he is at rest now makes me happy.

And considering that we are all new at this process, it was handled at all levels with grace and dignity.”

Allan Williamson’s assisted death was a first for Kabara and its associated aged care facility, Carramar, but it won’t be the last, with VAD teams in Queensland struggling to keep up with requests from terminal patients, now that finally it is a merciful option.

Voluntary assisted dying gives people who meet eligibility criteria, are suffering and dying, the option to ask for medical assistance to end their life. For further information phone 1800 431 371 or visit qld.gov.au/health/support/voluntary-assisted-dying