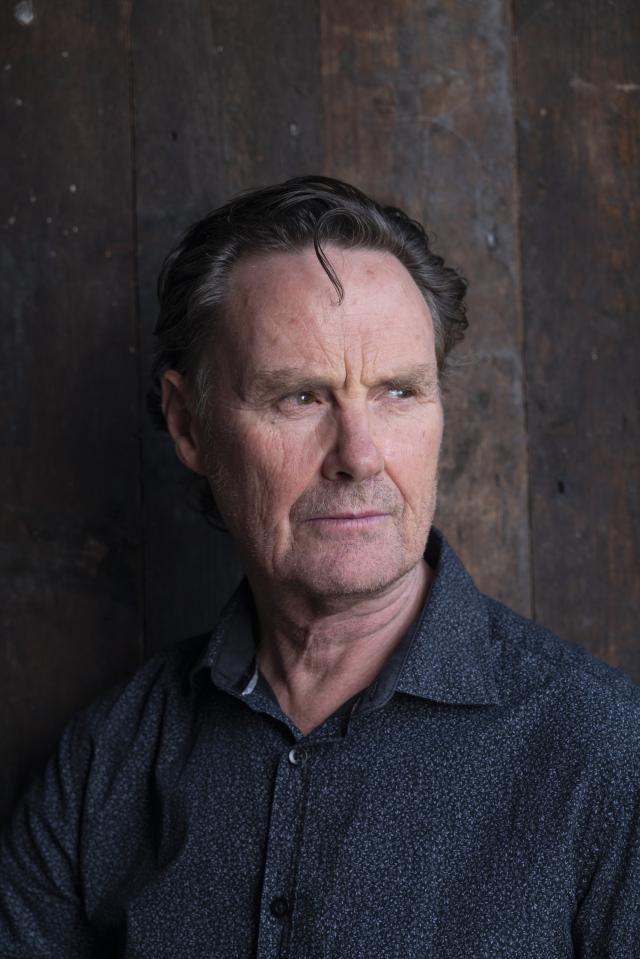

Neil Murray’s rough-edged, laconic voice comes crackling down the line, the first time I’ve heard it one on one for several decades, and I know immediately he’s on country.

“Yeah, mate. Lake Bolac, western Victoria, sitting in me off-grid shack as we talk. I spend a lot of time here now, mainly in the summer months, then in winter I’ll head north, which is what I’m doing next week.”

Indeed he is, playing two Sunshine Coast gigs this month, part of a national tour in support of his 10th solo studio album, The Telling.

“That’s my lifestyle these days – transcontinental drifting with the occasional gig.”

Now in his late 60s, Murray sounds older (don’t we all?) than when we became friendly in Sydney nearly 40 years ago, just as the Warumpi Band was attracting national attention with their first single, Out From Jail (Jailanguru Pakarnu), but he still has the happy knack of speaking in lyrics, like the bush bard he has been all of his career.

Back then, he’d come to the big smoke to drum up interest in the band, and ended up staying for several months, but the bush won him back, as it always has.

Born in western Victoria on Djab Wurrung country, Neil remembers as a small child his father and grandfather showing him what they called “blackfella stones”.

“They were millstones and grinders and things like that, and they’d tell me they’d been left there by the people who once lived on this land, which really puzzled me.

“I just loved being on the land, hunting and fishing and camping out, so when I was told that these blackfellas had lived there so many thousands of years ago, I thought they must know something about country that I could learn.

“I mean there were Indigenous kids in my school and we didn’t even know, although I have vague memories of one guy taking me aside conspiratorially and saying, you know what? No, what? I got blackfella in me! We both just giggled, but I felt a calling and it kind of grew inside me.”

After attending art school in Melbourne, while his fellow students took off for Europe or America, Neil followed his heart and went bush. A mate had been teaching at Papunya, the art-focused community north-west of Alice Springs in the Western Desert, so in the spring of 1979 he went up there for a look. He’d barely got back to Melbourne when the friend called to say there was a job going driving the stores truck around the outstations.

“Put my name on it,” he said.

Neil had only been working in Papunya for a couple of months when two Aboriginal brothers named Sammy and Gordon Butcher came to see him. They’d started a band and had heard he played guitar and sang a bit.

Says Neil: “Sammy was just a brilliant guitarist so we started jamming. He was great to play with because he wanted everyone involved. I remember I was unloading gravel off the back of a truck one afternoon and the guys came around with guitars and stuff hanging out the windows of an HD Holden and Sammy yells out, ‘Are you comin’?’ I said, ‘Comin’ where?’ Sammy said, ‘We’re going to Hermannsburg to play a gig. I looked at my boss and he nodded so I dropped the shovel and jumped in with them. That was the Warumpi Band’s first gig outside Papunya, before we even had a lead singer. Other than playing, my role in the band became to look after the whitefella business, hire the halls or book the gigs or whatever.

“They were great times, so much fun and a real sense of inclusion in their community. That’s where our early song Blackfella, Whitefella came from – ‘Blackfella whitefella, It doesn’t matter what ya colour, as long as ya still a fella’.”

Around the middle of 1980 a young Yolngu man named George Burarrwanga showed up in Papunya, hoping to marry Sammy and Gordon Butcher’s sister. (He did.) Turns out he could sing, and his vibrant personality added a new element, so George became the fifth Warumpi.

Neil was the main songwriter for the band but he struggled to write songs specifically for George to sing from his own perspective until he accompanied him to his home on Elcho Island in Arnhem Land.

Inspired by the simple, idyllic lifestyle, he penned My Island Home, which appeared on the band’s second album.

About a decade after the Warumpi Band had started, after they’d been taken under the wing of Midnight Oil and become international stars, Aboriginal artist Terry Yumbulul drove photographer Paul Wright and me about three hours on rough track from Gove to the Matamata homeland on the coast of the Malay Road, where a boat was supposed to pick us up to deliver us to Inglis Island, part of the English Company Islands. Even by Territory standards, it doesn’t get much more remote than this.

Terry took off on other business and we were left to spend the afternoon sitting in the shade of the mangroves, waiting and hoping.

Towards dark, a tinnie sped across the choppy shallows into the mud and a thin black man, with long hair and nothing on but a pair of bright red shorts, alighted bearing crab pots and a tub of turtle meat.

He asked after our mission, and when told said bluntly: “No boats comin’ here now, too rough. Youse blokes better come with me.”

We followed him along a muddy track to his shack and he introduced himself. “Name’s George.”

I asked him what he did out here.

“Nothin’ much. I’m a rock star.”

I didn’t think much about that until we were sitting by his campfire, munching on delicious turtle, when he said: “I’m the singer with the Warumpi Band. I wrote that song, My Island Home.”

“No you didn’t,” I responded, “my mate Neil Murray wrote that.”

“Yeah, he helped,” George said, and we all laughed.

When I tell Neil this story, there’s a long pause from the off-grid shack at Lake Bolac, before he says: “If George [who died of cancer in 2007] told you he wrote it, it’s because he sang it so often it became part of his identity, and it was his song. But it sticks in my craw a bit because for years I had people telling me I was a rip-off artist.

“It’s like that stuff about cultural appropriation. So far no one has ever accused me of it, but if they did my defence would be that the elders taught us that what really matters is what you have in your heart, not what colour you are.

“And My Island Home isn’t exclusively for Indigenous people, it’s for anyone who has ever missed their home.

“The Indigenous spirit behind it is that you are a part of that place, you are connected. So we started performing it and later on I had a bit of luck – which you need in this game – when a girl called Christine Anu who was singing in my backing band, The Rainmakers, recorded it and had a huge mainstream hit. That’s the main reason I’ve been able to have a career in music all these years!”

Which brings us to The Telling, a beautifully nuanced and honest album of original songs about various aspects of truth telling.

No Justice is a song about the frustration and the anger felt by people in the Territory about the tragedy of teenager Kumanjayi Walker being shot and killed by police in Yuendumu in 2019, but also about the broader context of deaths in custody and the Black Lives Matter movement.

My Yuendumu Song is a tribute to a Dutch-born resident of the much-maligned community for 50 years.

Says Neil: “Every year the band would go to Yuendumu sports day which coincided with this bloke’s birthday, and we’d end up at his house for a jam, and Frank would wander out with a trumpet and play these sad riffs, but he can’t play anymore because he’s lost too many teeth.

“I wanted to honour him because in most communities whitefellas will come in for maybe a year or three then shoot through, but Frank’s been there for 50, he loves Warlpiri culture.

“There’s so much negative stuff about the place and I thought this was a positive story. And that’s why it’s got Jack Howard’s [Hunters and Collectors] trumpet in it.”

Rainbow Serpent and a Mine, a collaboration with traditional owner Jack Green, brings devastating focus to the McArthur River zinc mine pollution near Borrooloola, while Tears of Wybalenna is a potent reminder of the injustices of early settlement in Tasmania.

Murray’s singing voice is lived-in, which only enhances the power of his lyrics in The Telling, which he hopes will aid understanding of the need for truth, treaty and voice. But he says: “People have to understand that there was always going to be dissent within the Aboriginal communities, because First Nations mobs don’t always agree, just as European Australians don’t agree on everything.

“I know a lot of grass roots people in the bush who are for it, but we tend to hear more from people who are not and say they represent them.

“But I think there is great goodwill and good intent behind the Uluru Statement, and as part of the process I think the Voice will have great symbolic value. If it doesn’t get up I think it will put things back terribly.”

Neil Murray’s The Telling Tour is in Queensland right through June. Sunshine Coast performances at Diddillibah Hall on 10 June and Eudlo Hall 18 June. Ticket information at neilmurray.com