You’re the voice, try and understand it

Make a noise and make it clear…

We’re not gonna sit in silence

We’re not gonna live with fear

– You’re the voice, 1985, by Andy Quinta, Keith Reid, Maggie Ryder and Chris Thompson

The song that John Farnham turned into an anthem had nothing to do with The Voice that pops up in every news bulletin today, but it was inspired by a similar feeling, that everyone deserves the right to be heard on the issues that are important to them.

In that case, nearly 40 years ago, it was the reaction of Chris Thompson, the lead singer in Manfred Mann’s Earth Band, feeling guilty after sleeping in and missing a rally for nuclear disarmament in London’s Hyde Park. He wasn’t there, but he too wanted to be heard, so he sat down and wrote a song with his publishing mates. Eh, voila!

Now people all over our country are writing their own songs, in many different ways, to express their views about the proposal to enshrine a voice to parliament and executive government for Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders.

Last week in these pages you met Margaret Landbeck, 82 years young, who walked 82 kilometres along the Sunshine Coast Pathway in support of the Yes vote, stopping to explain her position to interested bystanders along the way. Meanwhile, the man who inspired Margaret’s walk, former Liberal parliamentarian and ultra-marathoner Pat Farmer, continues his round-Australia run for The Voice.

Just two people using grass roots action to persuade their fellow citizens, but I have a feeling we’ll be seeing many more such activations over the coming months, from both sides of the debate.

But that’s what it should be – a debate based on views supported by the facts, not the litany of lies and false information seen in far too many social media posts on the subject, nor the hysterical media pile-on that actor Cate Blanchett had to suffer after expressing a mild and constructive opinion in favour of The Voice on the ABC’s 7.30 program on 4 July.

Cate may have drawn a long bow in comparing The Voice proposal to the fight for women’s suffrage 120 years ago, but her argument, supplied at the request of the host, should not have drawn the kind of fire it received from News Limited and other media.

Here, in part, is what she said: “It’s a strange time, but an extraordinary time for an extraordinary country. It does make me sad there is a lot of fear being generated about a really positive moment for us as a nation and we have to remember that the primacy of parliament is not under threat… But there is a certain ‘voice’ that is never really, in a non-partisan way, in an eternal way, represented at that table and that is an Indigenous voice, and it is time we evolved to include all Australians…The more inclusive cultures are, the more vibrant they are.”

The Australian and the Courier-Mail reported: “Hollywood actress Cate Blanchett has been labelled ‘preachy’ and ‘elite’ after urging Aussies to vote Yes in the upcoming voice to parliament referendum.

Blanchett’s political statement comes as the official Yes campaign said its new messaging would focus on the stories of Indigenous people instead of high-profile endorsements.”

This and other articles took aim at the “Hollywood actress” for her wealth (“an eye-watering $95 million”) and the fact that she owns a house in London, which apparently should deny an Australian citizen the right to voice an opinion, which brings us back to what the debate is really all about.

Northern Territory senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, a leading advocate for the No campaign, also weighed in via news.com.au: “Australians don’t need multi-millionaire celebrities living overseas telling them what to do or how to vote”.

I watched 7.30 as it went to air that night and didn’t think that Blanchett’s was a planned celebrity endorsement. No doubt she was aware that her support would make headlines, but the highly personal attack that followed may have surprised.

Certainly, the tall poppy syndrome needs to be avoided by the Yes campaign, which has more or less been recognised by its leader Dean Parkin, and which is why Noel Pearson, one of Australia’s best-known Aboriginal leaders and also a director of the organisation behind the Yes23 campaign, was out in full support for Margaret Landbeck’s recent walk but at pains to keep off centre stage and let the voice of “ordinary Australians” be heard.

However, Pearson did make one point several times on the two occasions he spoke publicly, as the walk started and ended, and that was to emphasise that the decision on The Voice would not come from the three per cent of the population which he represented, but from the other 97 per cent.

“The Uluru Statement From the Heart is an invitation to reconciliation on behalf of three per cent of the country. We can’t affect the outcome of the referendum. The three per cent that I’m part of can’t affect the numbers. We extend the invitation to the 97 per cent who must consider their response to the invitation, and that’s what this referendum is – a response to the invitation of the Indigenous people.”

Dean Parkin has underlined this idea of an invitation to white Australia, saying he hopes that “Australians want to be part of a national unity to recognise Indigenous people as the first people of our nation and to make a practical change in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people”.

The challenge will be to tame the hostile sections of the media, but for Indigenous Australia it was ever thus.

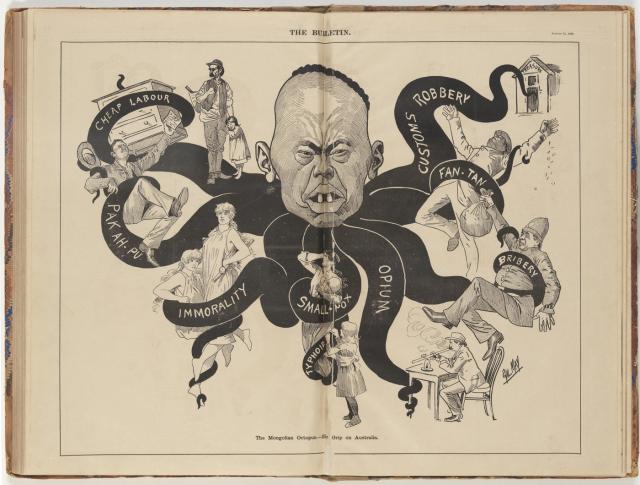

From 1985 to 1992 I worked for The Bulletin, a national news magazine then owned by Kerry Packer’s Australian Consolidated Press which had begun a storied century in 1880 with the message, “Australia for the White Man” proudly across its masthead, where, unbelievably, it remained until 1961, when the Packers bought it and enlightened editor Donald Horne immediately removed it.

But Horne’s enlightenment didn’t mean that “The Bully” had wrapped its head around First Nations’ issues, even after the 1967 referendum had voted to change the Constitution so that its laws would apply to Aboriginal Australians in the same way as other Australians.

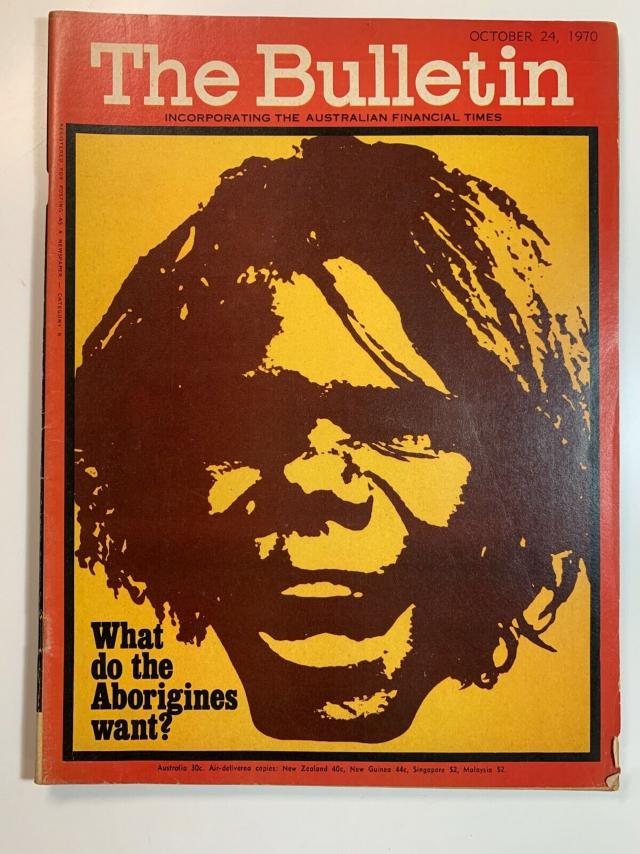

If anything, the magazine seemed confused about them, as evidenced by an October 1970 cover which asked, “What do the Aborigines want?”

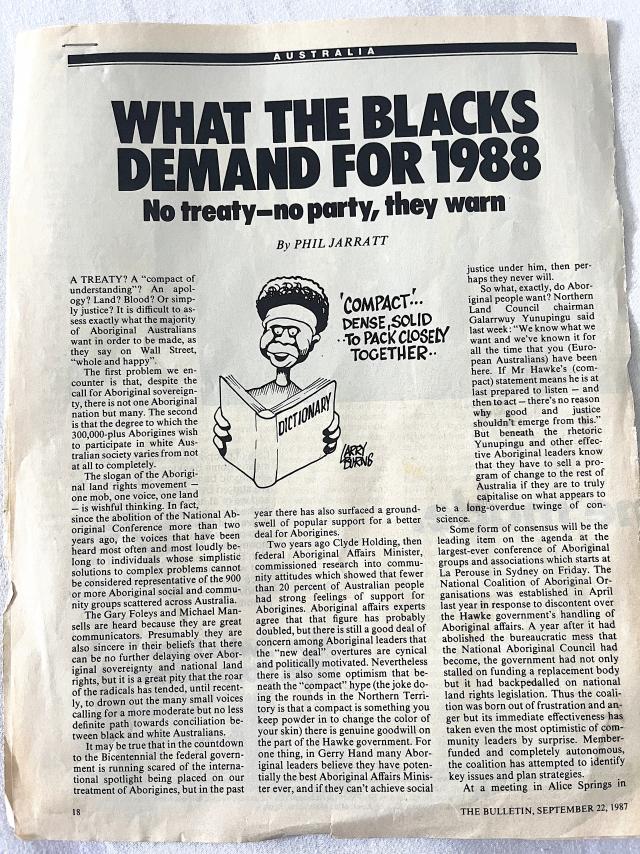

Although editorial policy had changed for the better and fairer by the late 1980s, a degree of confusion still reigned when in September 1987 my editors sent me out to discover why many high profile Aboriginal leaders didn’t want to celebrate the bicentennial of the European colonisation of their country.

I interviewed a long list of leaders including the Northern Land Council’s Galarrwuy Yunupingu, Pat Dodson, then national co-ordinator of Land Councils, his colleague Marcia Langton, chair of the Aboriginal Development Corporation Shirley McPherson, Charlie Perkins (who had the most conciliatory approach) and many more. Pre-native title, the key issue was a treaty, and the leaders summed it up with the line, “no treaty, no party”.

I submitted this as the headline for my cover story, in which I wrote: “The slogan of the Aboriginal land rights movement – one mob, one voice, one land – is wishful thinking… The voices that have been heard most often and most loudly belong to individuals whose simplistic solutions to complex problems cannot be considered representative of the 900 or more Aboriginal social and community groups scattered across Australia… [These voices] are heard because they belong to great communicators, but it is a great pity that the roar of the radicals has tended to drown out the many small voices calling for a more moderate but no less definite path towards conciliation between black and white Australians.”

I wouldn’t have written it quite like that today, but I don’t resile from it either. I was more than disappointed, however, when my headline was dwarfed by a rather angry “What the blacks demand for 1988”, and the article was accompanied by demeaning and politically incorrect cartoons.

That was 36 years ago, The Bully is long gone, and maybe we’ve all learned something about reconciliation in the intervening years and the next few months will see a respectful national conversation emerge about this important vote.

Noosa Today will play its part by presenting views from prominent citizens and readers representing both sides of the debate over the coming weeks and months.