I have been friends with the distinguished French photographer and writer Maurice Rebeix for more than 25 years, but his fascination and association with the Indigenous world is much older, taking in more than 40 years of learning and documenting the wisdom and lifestyles of the First Nations of the world, particularly the Native American tribes, with whom he spends at least a month a year.

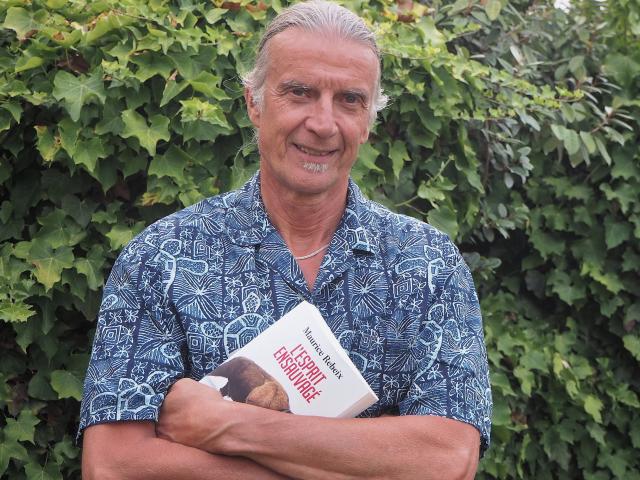

Maurice’s work has been documented in several books and exhibitions, and I have had the pleasure of working with him on a couple of these projects in different parts of the world. Now approaching 70, Maurice’s work took on new meaning with the publication in 2022 of

L’esprit ensauvagé (The Wild Spirit), a bold and highly personal exploration of the meaning of what he had learned from decades of close association with Indigenous peoples. One French reviewer of the book noted: “As well as for their resilience in the face of the treatments they have suffered and too often continue to suffer, all over the world, the main objective of the book is to transmit the message of balance, of respect towards all that these societies deliver, including the link with their animist and totemic origins. True whistle-blowers, Indigenous peoples send, confronted with the ravages caused by the blind exploitation of the planet, an invitation to wisdom and moderation that is increasingly relayed by others, including now by the scientific community.”

A year after Wild Spirit’s publication, and just weeks away from our own decision about whether we will listen to the Voice of First Nations, I sat down with Maurice at his home in the pays Basque of France and turned on the tape.

PJ: Tell me something wonderful you’ve learned from Indigenous people.

MR: From the Amazonia to the Aborigines to the North American Indians to the Hawaiians to the Maori, all Indigenous tribes believe that the way to the truth is the telling of stories. It’s not through academic study, it’s through the stories. The great-grandson of Chief Sitting Bull was in Paris in 2019 and he told his stories with great wisdom and great humour. He said: “When you tell stories you lift up the curiosity of people, take them on a journey, and if you make them laugh, they will think deeper about the meaning of what you said.” And the lesson here is that if you want people to understand, you make them laugh, and then they remember.

So I’m going to tell you a story about the picture on the wall right behind you. I did a collection of surf portraits and one of them was Tiger Espere, the former surfing champion and a Hawaiian elder. I asked each subject to choose a location for their portrait and Tiger chose a place just near the Dole pineapple factory where I noticed these trees, just a clump of them, and we met there in the parking lot and started walking towards the trees and he stopped and said, “First I need to pray for permission.” Through my years of working with Indigenous people I know what he means but I don’t know exactly what he’s going to do. He closes his eyes and turns his face to the sky. Then I did something I don’t usually do at this point. I took a picture. Usually in spiritual activity you don’t record it. You don’t use the technology of capture out of respect. But I did it and he heard the click of the Pentax and he did nothing so I took a few more. Then he walked me up to the stones next to the trees and explained to me where we were and what it meant. The point of the story is that asking permission of the elders, of the spirit world, is the way of Indigenous people everywhere. Yes, they cut trees, but they ask permission, because the tree is a living thing.

So Tiger walks me to the rocks which are lava slabs, one of the holy places of Oahu where the queens of ancient Hawaii would come to deliver their babies, in the natural way where things go from up to down. So the first contact of that newborn would be the lava rock which constitutes the island itself, the power of the volcano, and the connection between child and place would be established. But if you’re just passing by, it’s simply a nice place of rocks and trees.

The ideas behind Indigenous culture don’t differ a lot between tribes or nations, but the interesting thing is that they are the reflection of who we all were. If there had been no savages there would have been no civilisation. We are all descendants of those who were able to survive through their invention, technology, imagination and prayer. In that sense we are all Indigenous, but the people we now call Indigenous hold the keys to something we lost in the process, perhaps starting in the Neolithic Age when we first had the notion of “my land”, when hunter-gatherers became farmers. Or perhaps it came from the development of Judeo-Christian beliefs when they began to say they were the elected species whom God had told to take ownership of the land. Or perhaps it really began with the Industrial Revolution, when mechanisation reached its first level of craziness, and then progressed through to the rise of Oppenheimer, who was tortured at the end of his life by what he had created because he became a believer of the Bhagavad Gita, a devotee of Krishna.

My point is that when we talk about Indigenous we must never forget that they are the holders of the medicine that has been needed at this moment and over generations to keep the world on track. They are the ones ringing the bell, because we have become so detached from what made us. The concept of the environment as some detached identity we have to protect is offensive to me, because there is no environment that isn’t part of us. We are one and the same, the air, the water, everything is part of us. It’s a scientific understanding of who we are and how we operate within the aspects of creation. We can’t call things like water a resource and own them. Water is not a resource, it is life.

PJ: The other night over dinner you told me that five per cent of the world’s people are Indigenous but they count for 85 per cent of the world’s biodiversity. I went straight home and wrote it down. Can you explain that?

MR: I say this because the people we once called savages realised very early that they possessed certain qualities that made then different from animals, and over the ages this knowledge made us the masters of the rest of creation. It gave mankind the right to kill more fish than they needed to survive. But the Indigenous world moved at a different speed. They didn’t believe they had the right to kill animals to survive, they believed they had to seek spiritual permission. They did not see themselves as the masters but as the keepers, who have the responsibility of sustaining the natural world. That is a phenomenal difference of interpretation.

PJ: How did this fascination with Indigenous cultures begin?

MR: My personal journey into the Indigenous world began with childhood games. You know, cowboys and Indians, and years later when I explained this to my Sioux friends they didn’t find that ridiculous. In our societies people tell you to stop dreaming, to be realistic, but in those societies you are encouraged to dream. When a medicine man is asked to provide a name for a child, he will say he has to take a nap and dream that name. When a very important decision has to be made he will spend four days on a hill with no food or water while he waits for a vision. My Indian friends always tell me, “We don’t make decisions, they come to us.” Dreaming is one of the essential activities of mankind. Look at Freud! Look at your Australian Aborigines and the importance of their Dreaming. We have to listen to those dreams and be guided by what they tell us. That is why your Voice is so important.

PJ: You seem to have been given remarkable access into worlds that few people see.

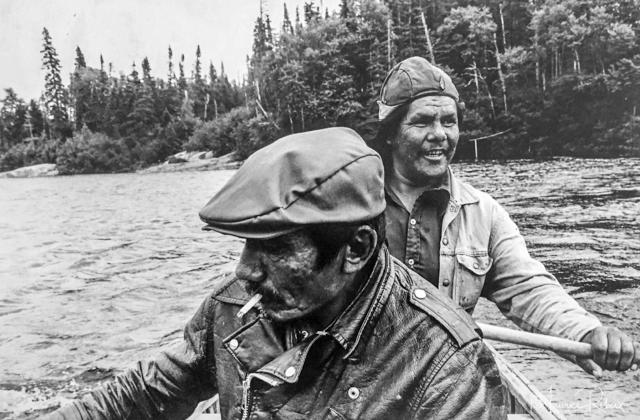

MR: As a photographer people are always telling you about the difficulties of photographing Indigenous cultures because they won’t let you into their spiritual world, but this is just not the case. I discovered this in Quebec, Canada in 1981, my first contact with an Indian tribe along the St Lawrence River, 1000 kilometres north of Montreal, a little village in the middle of nowhere, and there was a conflict over salmon fishing between the tribe and an American who had bought riverfront land and claimed it as “his”. He told the tribe they couldn’t fish this part of the river and they did anyway, and the police came with helmets and truncheons. I was there with a friend of mine, another photographer, and we waited there three or four days and nothing happened. We would walk around the village and people wouldn’t even look at us. And then it was like in making a movie. Someone says cut, and then you are in the next scene, sitting in a circle on the ground, all talking and laughing together. What struck me was a certain attitude, a certain sense of humour and, amazingly, a great sense of dignity even when everything has been taken from you. We were on the bank of the river just before dark waiting for the best conditions to fish, and I’d put a lot of strong repellent against black mosquitoes on my skin, hoping the Indians wouldn’t find it offensive. The guy sitting next to me sniffs a bit and says, “You got some more of that?” I pulled it out of my pocket and shared it with him. Not at all what I expected.

Also that night another guy gets up to go take a leak. We are on the river bank with a forest right behind us, and way beyond that a few cars parked in a clearing. He gets up and he walks past all these trees and takes his leak on the wheel of a car. For him this was the most appropriate place. It’s a small thing but it told me that we looked at the world in different ways. They don’t piss on a tree because it’s a living thing, while a car is just a piece of metal. I began to take on that perception of the world. When I climb a mountain I thank the mountain before I leave it. When I go into the ocean I introduce myself. Hello, it’s me again. People in our world might laugh at that as hopelessly romantic, but in the Indigenous worlds they will laugh at a man who says that a river is a resource providing so many litres of water. To them, that is far more ridiculous than talking to a mountain.