A trifecta of official openings of roads, bridges and a new beachside housing estate on Saturday 19 October, 1929, was the biggest celebration yet in the short history of Noosa Shire, but it is ironic that possibly the most important and historic element of this grand occasion has all but been forgotten.

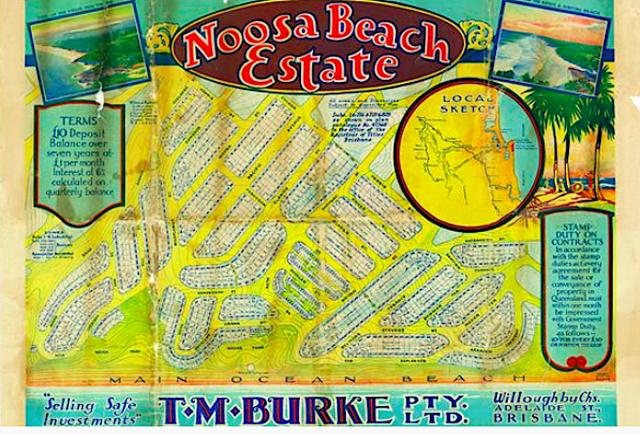

While Noosa Beach Road, eight kilometres of well-made, two-lane gravel, and the two state-of-the-art, humpback bridges over Lake Doonella and Weyba Creek that finally joined the river and beach communities as one Noosa, was a triumph of roadbuilding and economic flexibility – a Council trade-off of unwanted beachfront land for a vital transport corridor – which would usher in the age of motorised tourism access, the statutory plan for “Noosa Beach Estate”, produced for the developer TM Burke Pty Ltd by surveyor Ronald Alison McInnis, made national planning history.

It was the first of its type in Australia, described by the Queensland Home Secretary Jens Petersen as “one of the finest examples of town planning” and by the Town Planning Association of Queensland as “the first town in Queensland to be planned and zoned in advance of settlement … [which] marks an epoch in the history of town planning”.

According to retired town planning consultant Mark Baker: “While most texts attribute the first statutory planning scheme to RA McInnis’s plan for Mackay in 1934, my research leads me to consider his earlier effort at Noosa to be Australia’s first – albeit for a greenfield site rather than an existing settlement.”

Given that today, the 75 hectares of beachfront sold to TM Burke for £11,000 worth of roadworks in 1928 is the major part of the glittering multi-million dollar playground of the rich and famous that we know as Sunshine Beach, the estate’s ground-breaking planning history makes fascinating reading, and sheds new light on planning schemes to come, particularly the zoning controls introduced much later in the century to protect Noosa’s beauty and amenity.

Thomas Michael Burke began his real estate career in Melbourne in 1915 and by 1920 had established a branch in Brisbane, by which time, according to historian Denise Edwards, “he had honed his marketing, publicity and land development skills to a level which was attractive to the general public … Some of its earliest Brisbane developments are now among the more prestigious addresses in Brisbane.”

Among these were St Lucia Heights Estate in 1922 and Glenlyon Gardens in 1924. Adjacent to St Lucia Heights was the Coronation Park Estate, designed by the young Brisbane-based surveyor and planner RA McInnis, a Western Front AIF veteran and one of the driving forces behind the Town Planning Association of Queensland. Given relatively free rein by TM Burke, McInnis used the innovative and visionary concepts of town planning to inform his designs, and such was the case when Tom Burke turned his attention to Noosa in 1926.

TM Burke had already created a seaside estate at San Remo, near Southport, but when the company made its first foray into Noosa Shire, according to its annual report, “Thomas

Michael Burke looked towards Noosa and the surrounding coastline and with foresight that was a mark of this gifted man, saw a future for the area that was unparalleled by any other coastal resort in Queensland.”

The problem was access. Having just completed an all-weather road from Cooroy to Tewantin, the Council had no funding to complete a logical route to Noosaville and Noosa Heads. Early in 1928, a deputation of hinterland residents presented to Council a solution to the problem which was to sell land it owned to generate the necessary funds. The sale of land at what was then called “Coolum Beach”, which had reverted to Council ownership through unpaid rates since the 1890s, was still being considered when TM Burke proposed that in return for the purchase of the land, the company would build the five miles of all-weather road and two bridges required to connect the shire. For Noosa Council, this was a no-brainer, and as soon as the ink on the deal had dried, TM Burke forged ahead with their Noosa Beach Estate.

There was no question about who would design it, and in May 1929 TM Burke’s Queensland manager Lieutenant-Colonel JJ Corrigan DSO, a decorated hero of the Hindenburg Line, and RA McInnis presented their plans to Council. The two WW1 veterans did a convincing double act, with Corrigan talking up the community values of the plan while McInnis tacked it up on the wall behind him, all 12 feet by four feet of it. After less than an hour of deliberation, a healthy majority of councillors passed it, subject to the submission of a final version.

There was a growing interest in the application of the “garden city” concept, as reported in the Brisbane Courier a couple of months later: “The present plans contemplate the setting out of a town comprehending the best and latest ideas of town planners. Mr. T.M. Burke, a man with the widest possible experience in the layout of estates, is applying every modern improvement in the survey. Parks, playing grounds, parking areas, accessibility to the main artery, avenues, crescents, residential and business areas all take their part in proper precedence.”

But, as Mark Baker notes: “The key here was not that the Council agreed to the commercial transaction – a road for land plus subdivision transaction that would not pass the legal tests applied to planning decisions today … The fundamental questions arising from that 1929 meeting were: Why did TM Burke pursue a statutory restriction over the estate? He must have perceived it as an attraction to purchasers who would have been few and far between, but what benefit did they perceive? Secondly, why would the Council wish to encumber itself in these administrative arrangements where there was no existing problem?”

According to Mr Baker’s research, the town planning controls developed for Noosa Beach by McInnis “utilised a provision of the Local Authorities Acts 1902 – 1927 that enabled a local authority to designate lands and within these areas limit the use and occupation of lands and buildings, limit the height of buildings, limit the [site cover] and

regulate the [minimum area for subdivision].”

The strength of the town planning, however, lay not in the physical estate, but in statutory arrangements that accompanied it. An Order in Council identified three zones over the estate – residential, general business, and special industry, but as Mark Baker notes: “This was done not through coloured maps but by direct reference to lot numbers on a registered plan. However, the application of zones was not conceived as a static arrangement in the way that the legislation both here and elsewhere had proposed. Instead, McInnis incorporated a Table of Uses or Character Zones that provided for the establishment of a range of building types designed for specific uses. Within each of the zones these were classified as not requiring approval, those requiring approval of the council and a third category of prohibited buildings … These classes identified activities in a manner not dissimilar to current definitions of centre activities, light industry, general industry and noxious and offensive industries.”

“As a greenfield estate development,” Mr Baker writes, “the Noosa Beach Plan incorporated subdivision layout principles that were being advocated by the early planning practitioners. It did not however, have to accommodate the problems of an established urban form, including those of incompatible uses. The first statutory scheme in Australia to confront these issues was that prepared for Mackay in 1934, again by R A McInnis.”

He concludes: “The similarities between the structure of the Noosa Beach statutory plan and those that have followed are striking and bear testament to the robustness of the ideas and concepts developed by the early proponents of planning in Queensland.”

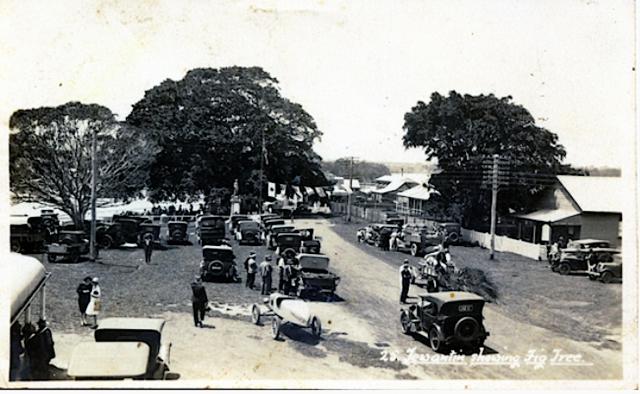

Meanwhile, back in October 1929, there being no Brisbane train on Sundays, the revellers partied on all weekend from Noosa Beach Estate to the inns of the real Noosa over the headland and back to the pubs of Tewantin.

On the Monday James Scullin was sworn in as Australia’s new Labor Prime Minister on a tide of optimism for social change, but by the time Monday reached the US there was pandemonium on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange as frantic selling wiped millions off some of the world’s biggest companies. Within a week the Wall Street Crash had triggered a depression that would soon be felt around the world, even in Noosa Shire.

It would be a couple of decades before Tom Burke could sell much of his beachfront land, and a couple of generations before Noosa’s true potential as a tourist resort could be realised. The name of T M Burke — the company, rather than the man — would hang over it like a polarising cloud for most of that time. But on that spring day almost a century ago, eight kilometres of rough “highway”, a couple of bridges and a clear-felled estate had opened the doors to an exciting, if challenging future.

FOOTNOTE: The writer has drawn on the work of Mark Baker (Visions, Dreams and Plans, 2012) and Denise Edwards (Conflict and Controversy, 1998) as well as his own Noosa history, Place of Shadows (2021). Next week we will look at the legacy of the planning pioneers and their impact on Noosa.