We’re staying at Umah Kembar, a beautiful compound of twin Dutch colonial bungalows and spacious gardens in the middle of the Balinese village of Pererenan, a place where, over the past 15 years from my office in the poolside guest quarters, I’ve researched and written four books and produced two documentaries.

We came here to mourn our dear friend Sue, one of two leaseholders of the estate, following her untimely and tragic death six months ago, but I also find myself mourning a village that we once loved.

Five years ago, pre-Covid, the writing was on the wall for Pererenan but I never expected it to get so bad so quickly.

It’s beautiful here in our gardens but we are virtually prisoners in the precinct. I used to ride a pushy down the quiet Jalan Pantai (beach road) with my surfboard tucked under my arm when the tide was right at any time of day. Now I go at dawn to get a few waves in before the traffic gets crazy and the breaks are completely taken over by tourist surf schools whose instructors show no mercy to old blokes on longboards.

Like everyone in Pererenan, we are surrounded by construction sites, jackhammers provide our daily soundtrack, tourists and couriers on scooters get around the standstill traffic by mounting what few footpaths exist, so it’s not safe to be a pedestrian.

And it’s become kind of weird.

The huge Russian and only slightly smaller Ukrainian presence means every menu is multi-lingual and it’s a lot easier to get a Kiev poke or a Moscow mule than it is a nasi goreng, Bali kopi or a cold Bintang.

And of course, every chilled out, cool one of these joints is a co-working space full of beautiful tattooed people in skimpy matching beachwear and never without earphones. It’s so earnestly try-hard cool that they’ve forgotten how to cook the basic staples we used to love.

After my early surf this morning I found a new place we could walk to in less than five fear-filled minutes.

Most of the space was co-workers only but we commandeered a corner table and ordered coffees and truffled eggs. The menu was Russian first, English second. The minimalist art around the walls consisted of a homily in Russian and English, centred on white space. “Face the void” declared one, “Everything has always been, is and will be” insisted another.

Suitably cheered, we threw down our eggs and got the hell out. Walking home, I noticed a frock shop window informing passers-by: “Too busy creating my dream life.” Well, good for you, Svetlana.

Russian tourism, by the way, has shown a slight decline over the past two years, falling out of the top five, which Australia leads with China just behind. But according to insiders, this is only because many more are entering on long-stay visas.

Of course, whether we want to blame the Russians or not, it’s completely futile to mourn the passing of an era that was never going to withstand the inevitability of the urban tourism sprawl, originally planned more than 50 years ago to be contained between the airport and the south-west coastal strip to the temple of Petitenget, but like all policies of containment in Bali, doomed to fail.

In 1971, in response to the 1969 opening of the Ngurah Rai International Airport and the sudden surge of tourism (arrivals trebled to 30,000 within the first year – in 2023 it was 5.3 million) the “Master Plan for the Development of Tourism in Bali” was drawn up by the Indonesian government as part of an aid program financed by the United Nations and carried out by the World Bank. Indonesian public servants worked with a French consulting firm to plan the expected growth resulting from identifying Bali as the “showcase of Indonesian tourism”.

The plan called for consolidation of the tourist hub and limiting development elsewhere, the philosophy being that in this way most of the island would remain unspoiled and culturally pure, and tourists could be bussed from their dormitories to gaze in awe and wonder on day trips.

When we started making Pererenan our Bali base all those years ago, the village was still outside the perimeter of the tourism hub, but only just. High rise and doof doof beach clubs had already taken over most of neighbouring Canggu, and in Pererenan, by paying double its value, you could lease part of the official green belt rice fields that formed an arc around it and build your dream villa, which by now will be surrounded at very close quarters by 50 others just like it.

Yes, many parts of Bali have reached tipping point, but there is always hope, or Kerta Yuga, in the Hindu belief.

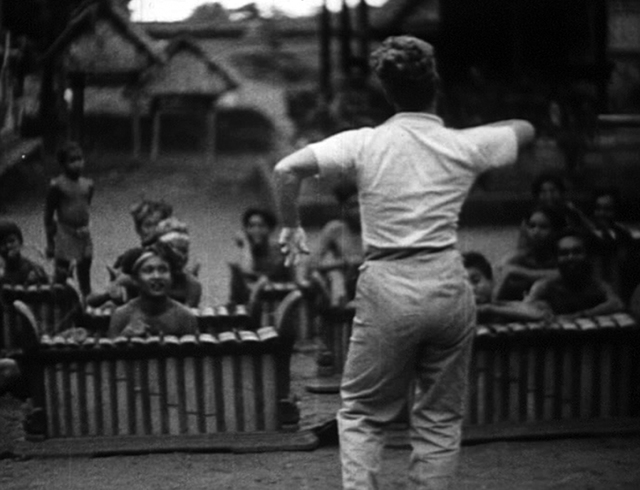

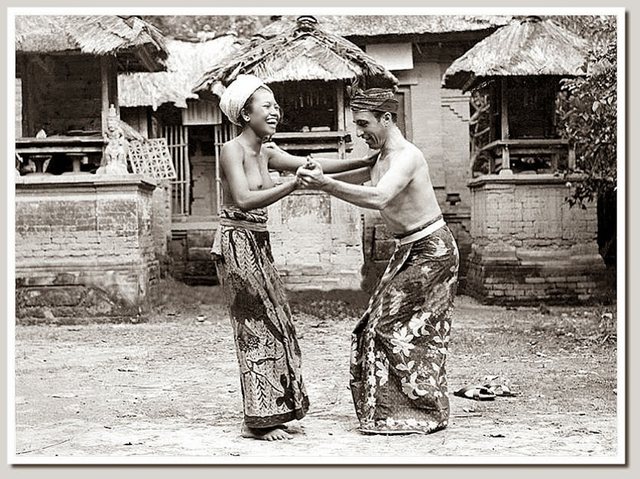

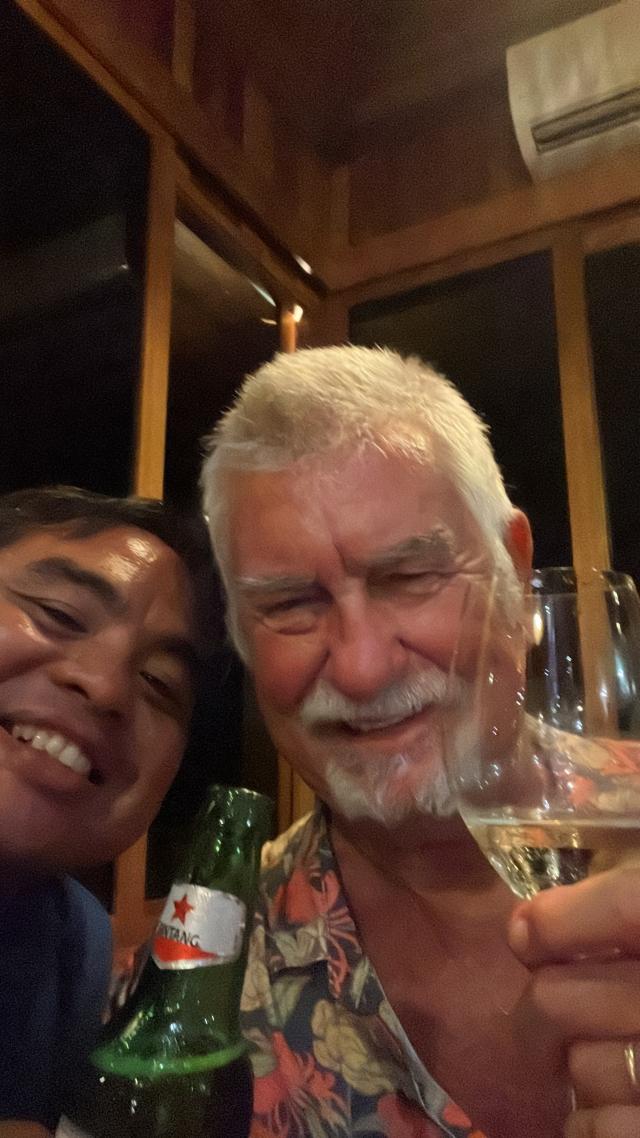

For us this past week that was brought home by our annual visit to Cepaka, just 10 minutes inland from Pererenan but untouched by it. This time we brought our extended family to pay respects to our friend Wayan Agus Parwita, his wife Made, brother also Made, their tribe of kids and the patriarch, I Nyoman Suwita, wood carver of temples, and matriarch Ni Luh Suji, in their beautiful compound, still surrounded by lush jungle.

I have told the story here of Wayan Agus, the man who saved the village during Covid by employing 800 people who had lost their hospitality jobs, so I won’t revisit it, other than to say that he is like a Balinese son to me, and I have been immensely proud of him since he drove me around Bali more than a decade ago, explaining the interweaving of culture, religion and economy, as I researched my book, Bali Heaven and Hell. Now a successful businessman working on sustainable building projects, Wayan walked us from the compound to his new restaurant, Café Baru, for a feast of babi guling, and yes, a few teary toasts to a lost past.

Next week we’ll visit a couple more outposts of old Bali.