Most Australians from school children to seniors know the story of Cook’s voyage along the east coast of Australia, charting and describing the land and its people.

But how many of us know the same story from the perspective of those on the shore?

First Nations people watched this odd-looking vessel come into their country, and saw strange people who disregarded their laws, took resources and tools without permission and sailed away.

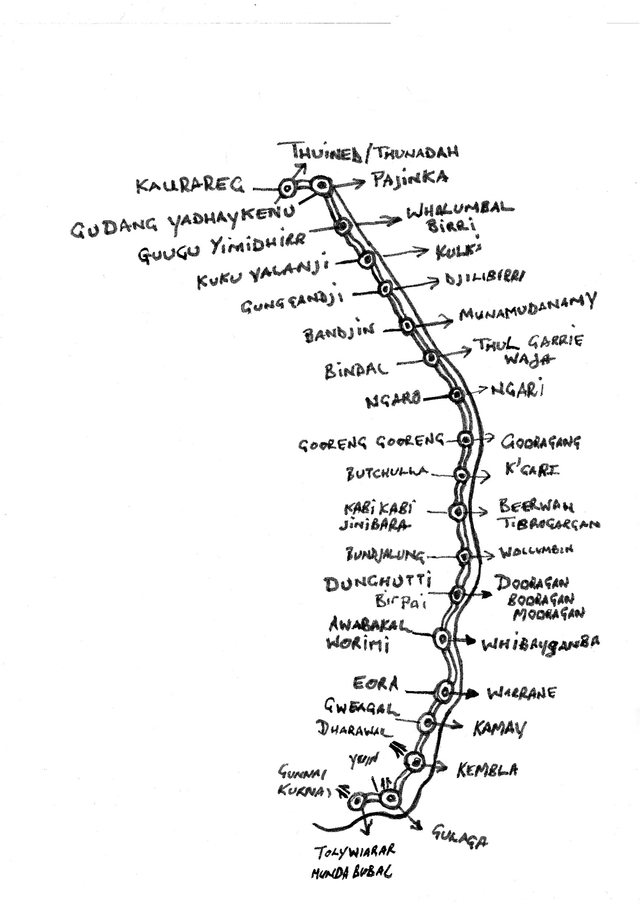

The people of south-east Queensland tell that they were forewarned of the endeavour’s coming by smoke signals and message sticks, and carefully watched the strangers to see if they might land as they had further south.

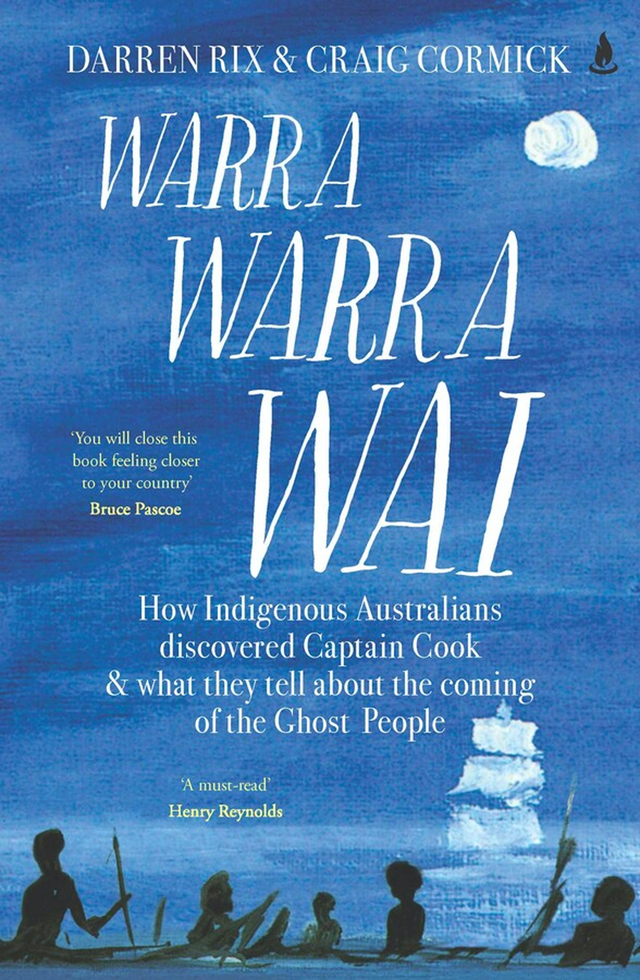

A new book out this month, Warra Warra Wai, tells those stories from the many different Indigenous people who lived along the east coast, putting back the original names and creation stories to landscapes that Cook renamed.

Cook named the Glass House Mountains after the conical factories that produced glass in England. The mountains, which lie on the traditional lands of the Jinibara and Kabi Kabi (Gubbi Gubbi) peoples, each individually have their own names and stories, in particular Tibrogargan, the father, and Beerwah, the mother.

Indigenous author Darren Rix, who grew up on the south coast of NSW, and his collaborator Dr Craig Cormick, travelled over 4000 kilometres, from the bottom of Victoria up to the Torres Strait islands, talking to First Nations people to learn what stories they told of the coming of Cook and his impact.

The book involved deep research in the archives as well as many oral histories, often correcting long-held assumptions.

For instance the phrase ‘Warra Warra Wai’, which were the first words called to Cook as he attempted to land at Kamay (Botany Bay) was long believed to mean, ‘Go Away’ – but is more accurately translated as ‘You are all dead’. This was a reference to a belief the light-skinned Europeans were spirits, or ghost people.

Co-author Dr Craig Cormick said, “Most people we talked to said, yes we have stories of Cook but what we really want to tell is truth-telling.”

“So the book also includes stories of dispossession and violence that are integral to any understanding of First Nations history.

“However the book also contains stories of hope, such as language and cultural revitalization and returning to Country.”

Craig Cormick and Darren Rix said storytelling is really important to better understand our nation’s shared history from both the black and white perspectives.

Karen Mundine, the chief executive officer of Reconciliation Australia has said of the book, “If we are to build better relationships and mature as a nation, these are the stories that Australians need to hear.”