Picture, if you will, a high school assembly area somewhere in an Australian city way back in the halcyon days of the 1960s.

It is filling fast because the high school’s very own teenage rock band, The Silver Monocle, is about to make its public debut. Three of the four band members enter the stage from the wings and make ready to play. Then the drummer whistles from behind his rig and a fourth member, barefooted and clad in flowing hippy robes, comes running through the audience and takes an athletic high jump onto the stage.

Spectacular stuff, but even better was to come. Unbeknown to Jumping Jack Flash, someone had pasted a gunpowder mix all over the stage floor, which, when trodden on, went off like a firecracker. As he landed and reached for his guitar, bangs and flashes filled the stage and the sickening smell of burning flesh hung over the assembly area.

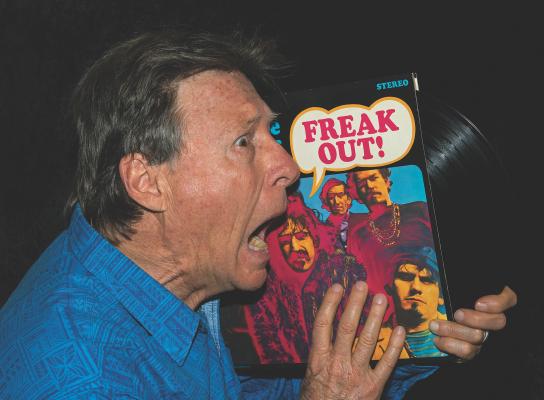

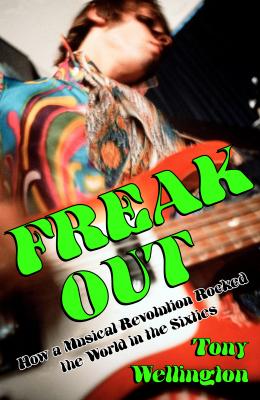

“As soon as I hit the stage, my footsteps set off crackles and sparks, which may have amused the audience but also burned the soles of my feet,” Tony Wellington, whose feet recovered and who later became mayor of Noosa, writes in the introduction to his fascinating new book, Freak Out.

Although these days Tony tends to dismiss his political career as a temporary aberration in a life of creativity, the same intense passion he brought to that job is evident in this account of how a “musical revolution rocked the world”. The detail is impressive. Even if you think you know the story, you don’t. But it is the heart and soul he puts into his description of an era that we baby boomers can never forget, that makes Freak Out essential reading, even if someone once contended that if you can remember the ‘60s, you weren’t really there.

I’ll leave the reviewing of the book to someone else on its publication in November, but having binge-read an advance copy of the manuscript in one riveted and sleepless night, I was intrigued by how it came to be, so Tony and I found comfortable cane chairs and a river view and chatted over a bottle of zero wine. (Well, we are aging baby boomers, after all!)

NT: Apart from losing an election and the arrival of Covid-19, what inspired you to write this book?

TW: I’d been cogitating on it for many years and I started to research it about five years ago when I was still in politics, but I didn’t have time to write it. In part it came about because I was curious to know why the music of my youth seemed so much more resonant than music seems now, even though I enjoy it very much. I wondered whether that was a product of just being young, or of the cultural milieu of the time. In revisiting those records of the time and researching them, I discovered that the ‘60s was a unique time, that music’s role was more fundamental then than it is now. I’m aware that this might paint me as an old fart, so I tried to not see everything through rose-coloured glasses. But what happened back then was that music had more universality because there was less of it. It was easy to keep up with it, whereas today there are nine million songs being uploaded every year. Now we’re overloaded with music, back then we were hungry for it.

NT: Early in the book you write: “It could be argued that the electric guitar was an essential tool of social reform.” Okay, argue it, please.

TW: Well, it became the primary instrument of the musical revolution of the 1960s, which resulted in the transformation of popular music in ways that had not been foreseen, but it also created anthems that reflected the radical social shifts that were going on. The electric guitar became hugely symbolic within the context of rock music at the time, particularly with the development of the Marshall “stack” amplifiers that enabled people to play stadiums. By the time we got to Jimi Hendrix, his performance of Star Spangled Banner at the end of Woodstock was seen as a revolutionary statement, but it was just a guitar solo. However, it was the nature of what the electric guitar brought to modern music that had never been experienced before. Without that guitar revolution of the ‘60s we would never have got to heavy metal or disco or anywhere else. Hendrix was asked if playing an anthem like that was a revolutionary statement and he said it was just a song he learned at school, so he thought we’d play it. But certainly within the context it was revolutionary. Let’s not forget that only a few thousand people were there to hear it. It was played on the morning after the festival had finished and people were packing up and leaving. But it concluded the Woodstock film and that’s what gave it pre-eminence.

NT: Speaking of amplification, I loved your account of The Beatles tour of Australia in 1964 when the sound systems were woefully inadequate. I was just a bit too young, but I remember older teenagers at the beach saying that the concerts were fab, you just couldn’t hear the music!

TW: The Beatles were amplified through a house system usually used for boxing matches. There was no mixing desk and the musicians had to balance the sound by moving closer or further away from their microphones. This wasn’t just in backward Australia, it was the same everywhere! Even their final US tour was the same. But by Woodstock in 1969, the technology had caught up and you could hear what was being played.

NT: Another quotation that surprised me: “Bill Haley’s Rock Around The Clock instigated a brief but significantly rebellious youth movement, including the first teenage riots.” Really? Two World Wars, conscription, civil rights campaigns, ban the bomb …

TW: I think teenagers had participated with others in earlier protests and riots, but this one inspired a very specific demographic, which was teenagers. And teenagers weren’t a thing before the ‘50s. Prior to that if you were a teen you were just expected to wear the same clothes and listen to the same music as your parents. Thanks to a whole range of factors, including the postwar economic boom and the baby boom, and better education, young people suddenly had money in their pockets and, for the first time, the notion of a teenager became widespread. When Alan “Moondog” Freed created the first rock concert in the early ‘50s it was pitched at what was referred to as “teens”. Over the period of the ’50s and into the ‘60s, young people started to distinguish themselves from adults. It was cemented in the ‘60s with the mantra, “don’t trust anyone over 30”.

NT: Most of the book targets just a handful of years from the early ‘60s to ’69, when the emerging rock culture joined forces with the protest movement, but the messages of many of the most popular songs of the era were not always nice ones, were they? A lot of it wouldn’t wash today.

TW: No, that’s right. Particularly the Stones’ approach to women which was completely Neanderthal. Not just them of course. It was a surprise to me just how ubiquitous that approach to women was in the ‘60s, when you go back and listen to a lot of the lyrics. I think the Stones were the worst misogynists because they wore it like a badge of honour and with a sense of pride. They got older, had children and reformed, of course.

In that sense, you could argue that the musical revolution of the 1960s didn’t achieve much, but in other areas there were lasting advances. Of all the causes and movements that sprang out of the ‘60s, arguably gay liberation is the one that has made the most gains. In part that was because, without even really knowing it, the ‘60s was challenging sex roles. When Mick Jagger performed the free concert in Hyde Park, London in 1969, he wore a white dress and a choker. Part of the idea of being rebellious, was for men to take on a more effeminate look, and that possibly made it easier to accept different forms of masculinity.

NT: What were the songs that inspired you as a young teenager in the late ‘60s?

TW: I had singles by The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Normie Rowe …

NT: Ah yes, It Ain’t Necessarily So.

TW: That was an extraordinary song, and I did have that record. It was a strange choice for a hit record and of course it got a lot of kickback from the believers, but it was yet another example of young people expressing rebelliousness in a fundamental way, because they didn’t like the status quo. They didn’t like the Cold War, they didn’t like Vietnam, they didn’t like conscription, they didn’t like the way young people were being treated, and they believed they had the power to change it. It was pretty arrogant, but it was also superbly idealistic.

NT: Let’s go back to the music that inspired you back then, and inspired you to write this book.

TW: I could nominate a few albums. Like Easy, The Easybeats; Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, The Beatles; The Best of Eric Burdon and the Animals Vol.II; Smash Hits, Jimi Hendrix; The Crazy World of Arthur Brown; Kick Out the Jams, MC5; Spirit; Absolutely Free, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention; In the Court of the Crimson King, King Crimson. As for individual songs that had a seminal impact, that’s much harder. But I could nominate: It Ain’t Necessarily So and Shakin’ All Over, Normie Rowe; Help! The Beatles; Hey Joe, Jimi Hendrix; Good Vibrations, The Beach Boys; Sunshine of Your Love, Cream; Fire, The Crazy World of Arthur Brown; Piece of My Heart, Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company; Eve of Destruction, Barry McGuire; Brown Shoes Don’t Make It, Zappa and the Mothers.