A decade or two ago a friend of mine was helping with a spring clean at a local newspaper office when she noticed an ancient manila folder poking from an overflowing rubbish bin.

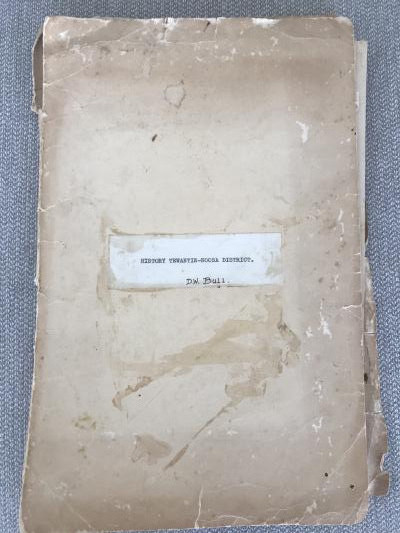

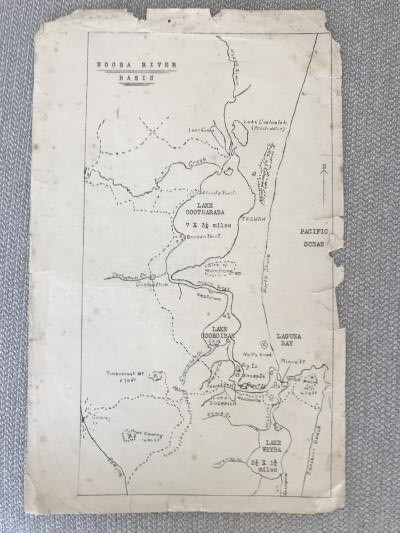

Closer examination revealed it to contain some 40 foolscap pages of typewritten notes plus maps of the Noosa River basin and Country of the Kabi Tribe, under the general heading Tewantin State School Project – History of the District, all of it yellowing and falling apart. Since none of her colleagues were remotely interested in the documents, my friend took them home, marvelled at the tall tales and true that lay therein, and filed them away in a safe place.

Only after the publication of my Noosa history, Place of Shadows, did she remember the old yellow folder, and asked if I’d be interested in seeing it.

As it turns out, it’s a fascinating collection of random pieces of Noosa history and folklore, some of it now thoroughly discredited, but with the distinct advantage of having been compiled when many of the protagonists were still alive. The ability to actually talk to early settlers like John Tedford and Charles St John Carter, and the widow of the notable Kabi Kabi linguist FJ Watson, offered so much more depth than this slim collection provides, but it was conceived and executed as a school project back in 1957, when precious little written history of our shire existed.

However, as this salivating researcher was soon to discover, the folder my friend discovered is not the only one in existence. Dr Ray Kerkhove, one of two historians in residence at Noosa Library last year, uncovered a copy in the Heritage Noosa collection and used it as one of the sources for an excellent paper called No Sir and Tea-Want-Him – Naming Noosa and King Tommy’s humour. Perhaps there are more quietly rotting away in filing cabinets or lining the lino in Noosa’s few remaining heritage homes.

But the copy I’m holding is pretty special and possibly unique for a couple of reasons.

The first is that under the title on the front of the manila folder is the ink-inscribed name, DW Bull. The second is that on the inside of the folder and on the final page of the notes is the name Howard Parkyn written in ink in different handwriting. While David William Bull was one of the major contributors to the collection, he was neither the organiser nor the editor, those credits being shared by Chas McKenzie and Vera Young. So was this Dave Bull’s personal copy? And was it later owned by pioneer businessman Howard Parkyn, a third generation member of one of Noosa’s founding families?

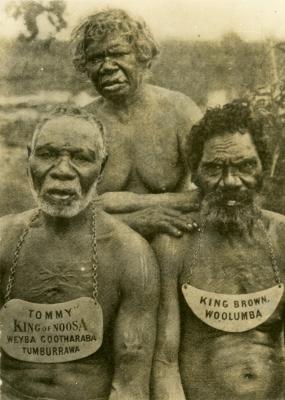

The parts of the Tewantin School’s now 64-year-old collection that most interested Dr Kerkhove were the myths about local place names that were to be perpetuated by DW Bull and later historians, including Colin Monks and Dr Nancy Cato, and the impact these had on our perceptions of Noosa headman (elder) King Tommy and the general Kabi Kabi population more than a century ago. Kerkhove credits linguist Fred Watson, who in the early part of the last century was the most distinguished member of the Queensland Place Names Board, with first casting doubt on the Aboriginal derivation of Noosa, and publishing the story that it came from a Kabi Kabi man responding ‘No, sir’ when asked by a white man if he knew the name of the place where they were both standing.

If the paternalism of that yarn offends, consider the alternative derivation of Tewantin offered in the Tewantin School history, probably written by Bull, who expanded on the theme in his posthumously-published book, Short Cut To Gympie Gold: “The spokesman for the aborigines, King Tommy, used to go to the Mission Station for food – flour, tea, sugar, and for tobacco… Mr [Reverend] Fuller had again and again to refuse Tommy, who, losing his patience, clenched his fist and shouted, ‘Flour, baccy, sugar!’ As he went away he remembered he had not mentioned tea, so he turned around and shouted, ‘Tea – want – um!’

(In his own book, written at around the same time as the Tewantin School papers, Bull claims that he heard both these naming stories from the ‘father of Noosa’, Walter Hay, perhaps believing this would lend them some credibility.)

There are people in Noosa even now who believe this racist nonsense is how Noosa and Tewantin got their names, but in his paper Dr Kerkhove thoroughly and systematically debunks the mythology by revealing a timeline that proves that both names and current spellings were in use in maps and charts before King Tommy was nine years old and presumably not yet a spokesperson for his people. Kerkhove also provides evidence that King Tommy, who in later life became a tour guide, had a wicked sense of humour, and often made up silly place name stories as a kind of “revenge” on pompous tourists.

For this writer, equally as interesting as the naming myths in the Tewantin School papers are the recollections, spoken and written, of the pioneer settlers, such as Charles St John Carter, described as “the oldest living Noosa boy… He remembers the names of all the boys he went to school with [in Tewantin], the old coach days and the roughly made bush roads they had to travel over. The first change of coach horses from Tewantin [en route to Gympie] was at the Five-Mile stable and Jackson’s Hotel, where refreshments were available, then the Nine-Mile and afterwards on to the Halfway House and stable (later named Cooran).”

John Tedford, born in Tewantin in 1878 and a successful fisherman and passenger launch proprietor on the Noosa River in the early 20th century, wrote lengthy accounts of early Noosa life, including his own Walter Hay story, concerning Hay’s first visit to the site of Tewantin: “He rode down to the Noosa River and set up his tent at the Fig Tree, near which the post office now stands. Outside the tent he set up his fire-place … When the natives … saw the smoke, they came over Doonella Lake to investigate. The leader was a big man (later known as Sergeant Brown) and accompanying him were about 20 other natives.

“Brown asked Mr Hay for some ‘tucker’ and, though he had very little himself, Mr Hay gave them some. Then Brown asked for tobacco. When Mr Hay said he did not have any, Brown up with his nulla and struck at Mr Hay’s head as he bent down over the fire … Mr Hay, drawing his revolver, blew up the ground around Brown’s feet. They all ran back over the lake screaming and never came near him again.”

Far too many of the stories in these papers, produced for the use of 1950s schoolchildren, depict First Nations people as lazy, demanding, violent and ultimately cowardly, just half a century after the European settlers and their police perpetrated the most cowardly act of all in forcibly removing the Kabi Kabi from their country.

But the Tewantin State School was hardly alone in this. At the time its History of the District was published, Australia’s leading news magazine, The Bulletin, was still running the line, under its masthead, Australia for the White Man.