Precede

You farm on flood plain because it’s the best ground, it’s beautiful, fertile soil.

You expect it to flood, and probably every year there’ll be a couple of small ones, and maybe every six or seven years the water will come up gently onto the flat. You lose your fences and you get on with it. But you don’t expect this. – Mary Valley farmer Gordon McWilliam, May 2022

Gordon McWilliam is standing at the edge of a cliff where once was a dam, up in the wild back country of his beautiful 343 acres that stretches from the banks of the Mary River at Moy Pocket near Kenilworth.

When we talk, it is just two months since the unexpected happened.

The swollen river broke its banks and the floodwater roared across the alluvial plain, destroying everything in its path, including 500 laying hens.

A matter-of-fact man who is used to accepting the good with the bad in life on the land, McWilliam shakes his head gravely as he looks over the cliff at the wreckage of the highest of a series of spring-fed dams, that was to have provided sustenance for 150 head of beef cattle this winter.

“It’s going to cost over $100,000 to make this right, so hopefully there won’t be another one like it for a long time. If it gets to the point where you’re up for a hundred grand bill every couple of years, who’s going to farm? Who’s going to provide the food?,” he said.

“Not only is climate change bad for the reef, bad for tourism, but we won’t be able to eat!

“But I’m not walking away. It would take an army to get me out of here.”

Gordon McWilliam, whom we’ll meet again later in this series, embodies the spirit that I found all over the Mary Valley last month when I set out to track the course of the river and discover the realities of living in one of the most flood-prone parts of the country, and how the resilience of its European settlers has been fostered over more than 150 years.

Mary River Springs

Along the Stanley River Road that follows the ridges of the Conondale Range out of Maleny, in the locality of Booroobin, you’ll find a striking laser-cut metal sign marking the entrance to a property. It reads: “Mary River Springs, Genesis of the Mary”. Beyond the homestead and farm buildings, the land falls away to spectacular views of the beginnings of the Mary Valley, and down the hillside are the “many small springs”, as described in early maps, that form the headwaters of the river.

Mary River Springs is now owned by Queensland grazier Simon Gedda, who, with wife Sue, has pioneered regenerative farming practices at his cattle property in central Queensland for more than 30 years.

Local conservationists are delighted that this historic, sensitive and slip-prone property is in such good hands, but since the owners were away, I couldn’t explore the springs myself.

Fortunately, Mary River Catchment Co-ordinating Committee chair Ian Mackay had done just that a few weeks earlier.

“The top of the property has considerable remnant vegetation and the outlook, particularly to the north and west over the Conondales, is magnificent … Walking down the steep, heavily grassed hillside, my boots experienced what ‘many small springs’ meant, particularly as it was only a few days after flood rain.

“We squelched our way downhill to a rainforest gully noting a number of springs along the way,” Mackay wrote.

“Apart from an impressive view, the other characteristic of this country is its propensity for landslips.

“Water percolating down to the basalt below acts almost like ball bearings allowing the soil above it to start to slide down the hill. We saw no shortage of slips, big and small, as we followed the water downhill.

“As you’d expect at the head of a river, the country formed a giant amphitheatre with all gullies funnelling toward the bottom and into a big dam, constructed some 30 years ago, and this was this was the start of the Mary.”

This was also the route taken in 1843 by the Crown Commissioner for Lands, Stephen Simpson and German-born Reverend Christoph Eipper who had set out from Moreton Bay to find a site for a new Aboriginal settlement in what was known as the Larger Bunya Country.

Eipper had apparently travelled in the area previously with just a couple of others, befriending several Aboriginal mobs along the way but, as historian Dr Ray Kerkhove has noted, this expedition was more like a military exercise. They were accompanied by 12 soldiers, a team of bullocks and a dray, and as guides the two former convicts, James Davis and David Bracewell, who had escaped from Moreton Bay and lived for long periods with the Kabi Kabi.

Interestingly, Bracewell had been with explorer Andrew Petrie the previous year when they discovered the mouth of the same river and named it the Wide Bay River.

On this journey they encountered few of the Traditional Owners but they did experience the wild and difficult nature of the headwaters country before finally discovering the flood plains known to the Aboriginal population as Hinkan Buman, now known to us as Kenilworth. While the idea of an Aboriginal outstation was soon abandoned because of the difficulty of access, the expedition paved the way for later settlement.

Long before there was a Bruce Highway, or even a coach road along the coastal route north, there were three routes that traversed the Conondale Range and were used by early explorers and settlers.

The most direct, and also the most dangerous, approximates Simpson and Eipper’s route in 1843, and is now known as Postman’s Track.

On the first fine morning in weeks, I nudge my little town car down the first incline and shudder at the condition of the narrow road at the first major bend. It reminds me a little of those clips of tourist buses on goat tracks in the Andes that crop up on social media from time to time, but I take a deep breath and acclimatise.

As the name implies, this track was once used by the weekly packhorse postal service which would carry the mail down the mountain and bring milk and cream from the dairy farms back up.

But even before the Mary Valley settlers arrived in numbers, it was used by hundreds of gold seekers on their way to the Gympie gold fields following Nash’s 1867 discovery. The only transport that could successfully cross the range were bullock drays or desperados pushing wheelbarrows and tramping along on foot.

It’s still rough, but, my god, it’s beautiful, and at the bottom of the escarpment and along the valley a bit, I turn onto Policeman’s Spur and head back up towards the source to a soundtrack of the babbling brooks that are on their way to becoming the Mary River.

When I run out of road I know I’m getting close to the hideaway of long-time resident Di Collier, but in fact there are still swollen streams to ford.

Fortunately, Di arrives just as I’m wondering which way to turn next, and guides me to her property, where she discovers she’s been riding on a flat tyre. Out here where the trams don’t run and the RACQ certainly doesn’t visit, when it comes to replacing a tyre, Di is on her own. But it’s always been that way.

Di Collier cringes a little at words like hippies and communes, but she’s been a fellow traveller with free-spirited alternate lifestyles for at least the last 50 of her 70 years, dropping out of university in Melbourne and roaming from an isolated farm in West Cooroy to a forestry hut in Cooloolabin near the pioneering Starlight Community.

“I’d been immersed in that kind of lifestyle for quite a while, so it was no surprise I ended up here,” she said.

“The land was quite cheap because it was the never-never. You had to go to Nambour to shop, and people there didn’t even know where Conondale was.”

The property Di and her then-partner bought in 1975 is now officially Conondale.

Unofficially, it’s “half an hour from anywhere” on bad dirt tracks and creek crossings. It’s unimaginably remote, not so much in travel time but in the sense that you are in a densely wooded and beautiful ancient landscape. And what Di has created here is pretty damned special, but it wasn’t always thus.

She and her partner wrangled a deal to buy a parcel of the vast Kennedy family pastoral holdings that once stretched from Kilcoy Station, notorious for the poisoning of Aborigines after the theft of some sacks of flour in the 1840s, all the way to what is now Postman’s Track.

But by the time Di moved onto the land she’d broken up with the partner and had a son.

“We moved into a substandard hut with three half-walls, one side totally open, no power, no generator, just a kerosene lamp and an outside campfire,” she said.

“Someone gave me a sheet of canvas that I could put up in winter. I suppose it was exciting, an adventure. It gets very cold here in winter, especially down by the creek, but I didn’t think of it as hardship.”

But back then Di says she was a complete novelty to the local farming community.

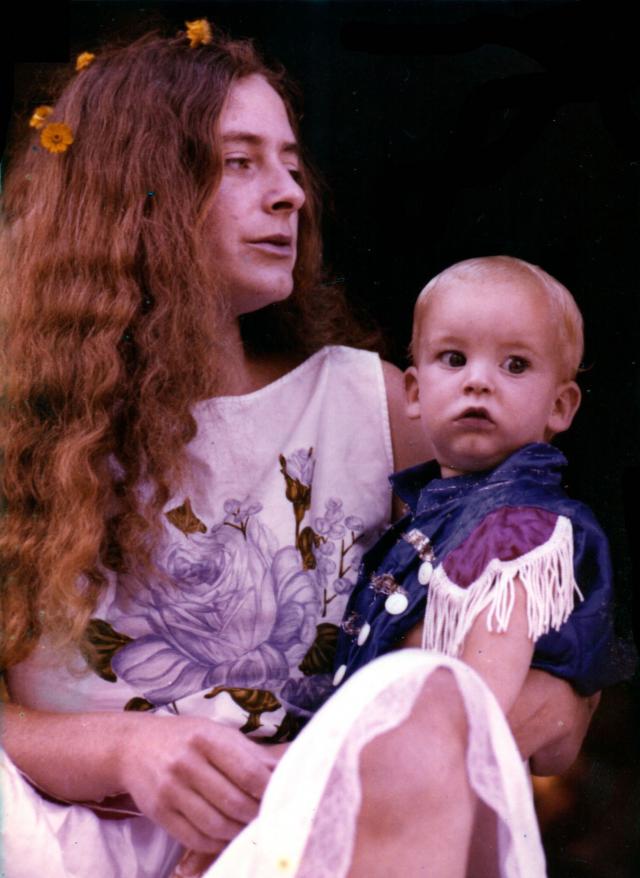

“One day there was a guy on a horse at the creek and for ages he just looked at me, standing in front of my hut with a baby in my arms. He didn’t say a word, he was just gobsmacked.”

To be honest, I’m a little gobsmacked today.

From the time her son was three, Di has worked at creating a tree-top hideaway she shares with the wallabies and the snakes, with a main house, a stone guest cottage and a studio. It is totally enchanting, but it speaks of decades of hard work in building and maintenance that is ongoing.

When the floodwaters come storming down the swollen creek she can be stuck here for weeks.

That word resilience comes to mind again.

Starting with the Crystal Waters permaculture estate soon after she arrived, a community of like-minded souls has grown up in pockets of the valley around her, escalating during Covid, and a few creature comforts have flowed.

“When I came here. the school bus would deliver your groceries as well as your kids, and the Conondale general store didn’t sell milk because everyone was a dairy farmer,” she said.

“Whatever you could buy there had to be measured from a sack. But now they even do a decent coffee.”

For the last 25 years or so, Di Collier has been involved in environmental restoration work.

“That’s my passion. I want to spread the word without preaching to the people who are settling all over the valley.

“This is why I’ve started doing community workshops.

“I’ve done walks to the springs, we’ve had a frog field trip, finding endangered species, and because I’ve got 168 acres up here and I’ve been weeding it for decades, we have weeding workshops.

“It’s about building community cohesion, to build a love for the river amongst the new people. The headwaters are of such ecological importance, and it’s something that connects everyone. I don’t tell them how to think, I just show them what’s here.”

In Part 2 of Proud Mary next week, the author takes to his e-bike to meet the characters of the lower valley.