By Phil Jarratt

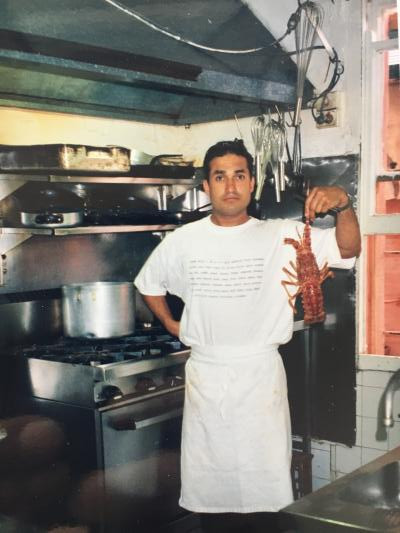

Peter Kuruvita’s CV reads like a who’s who of the great and the good of the kitchen across several continents.

The names of the restaurants in which he has worked and the chefs and restaurateurs who have nurtured and inspired him are synonymous with the restaurant histories of London and Sydney and many points in between. In Europe think the Roux brothers, Thomas Keller, Charlie Trotter, Raymond Blanc and Marco Pierre White. In Australia add Neil Perry, Greg and Peter Doyle and Michael McMahon. Now stir.

And yet the man who has made the cuisine of Sri Lanka his own humbly gives the greatest credit to his grandmother Achie, and her soot-blackened kitchen in Colombo, where his passion for cooking took root as a small child.

A Noosa resident since 2013, along with wife Karen and two teenaged boys, Kuravita, now 58, recently ended an eight-year partnership with the Sofitel Noosa Pacific Resort, where his signature restaurant, Noosa Beach House by Peter Kuruvita, became world famous for its fusion of Australian and Sri Lankan cuisine. After a storied career of 40 years you might expect him to be enjoying a bit of downtime, but that’s not Kuruvita’s style.

Instead he is spending long days directing construction of Alba by Kuruvita at Noosa Springs, a space that will host a café and pizzeria, cocktail bar, restaurant, providore, cooking school and event area. It may well be Kuruvita’s most ambitious project yet.

Amidst the jackhammers and the nail guns, we sat down to discuss a life that begins not in Sri Lanka but in London, to which destination Kuruvita’s father, Wickramapala Kuruvita, had ridden his motorcycle from Colombo in 1953 to see the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, missing the historic event by a matter of days. But if this was an inauspicious start, Kuruvita Sr, a man who could turn his hand to anything, soon made up for it by starting his own engineering business and falling in love with Liselotte Katharina (known as Lilly), a recent arrival from Austria who was studying to be a Montessori teacher.

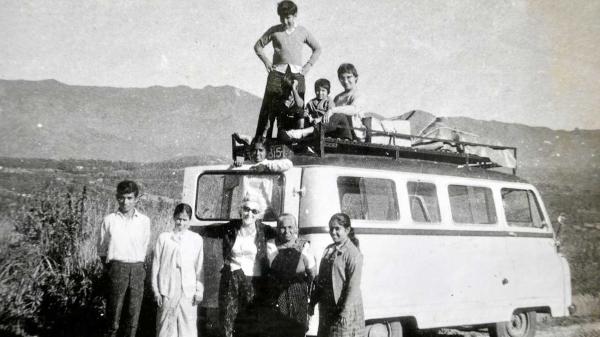

By the end of the 1950s the Kuruvitas owned a house in Fulham and had started a family. In 1963 second son Peter was born at St George’s Hospital, but he was only just starting to enjoy London life when Wickramapala made a momentous decision. He had managed to buy a blue Austin minibus which had been used in the making of the cult TV series Thunderbirds. In this, he said, the whole family – four-months pregnant mum, dad, eight-year-old Phillip and four-year-old Peter, plus a ring-in cousin and the unborn David – would travel overland to Colombo.

The prodigal son would return! The great adventure of being a Kuruvita was clicking into gear for little Peter.

In February 1968 the Thunderbirds bus full of Kuruvitas and virtually everything they owned began an arduous journey that would take them first to Austria to see Lilly’s family, and then across (then) Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan and India, to finally deposit them on the southern tip of the subcontinent where, Peter would later write, “Dad was about to try and jump our minibus off a rickety wharf onto two linked dugout canoes, which would paddle it out to a ferry where it would be hoisted aboard to complete our journey”.

At Alba Peter pauses for the jackhammer man to take a break, and says wistfully: “I still have wonderful memories of that trip. It was six or seven weeks of high adventure, but what I didn’t know was that it was only just beginning. My mum and dad were both great adventurers so as a kid the adventures just kept coming, but I think those formative years living in Sri Lanka made me the man I am. My values were formed during that time.”

The Kuruvitas moved into the big family compound in Colombo and Wickramapala set about replicating his London success in his homeland. Says Peter: “In London Dad had bought a whole shipment of lathes and shipped them to Colombo where he built a massive workshop on land the family owned. In those days you couldn’t get anything much mechanical in Sri Lanka, so he was going to make it. My father made everything for everyone, from car parts to sewer pipes, and Colombo Sewerage is still using them! He also found time to go to Germany and buy a brand new 220SE Mercedes. The speedometer would change colour as you drove faster, from green to red. We loved it!”

Despite dad’s business successes, life beyond the compound was sometimes hard for Peter. He recalls: “I was a bit of a loner. I went to an international school and I only had two friends, the American ambassador’s son and the Swedish ambassador’s son. It was a bit hard, being a half-Sri Lankan in that situation. My father wasn’t allowed into the swimming club, for example, even though he paid for the membership. Fortunately, things like that began to change while we lived there.”

Peter found solace, and himself in his grandmother Achie’s kitchen. He says: “I think I was the only one of the children who took an interest in it, but for me it was an endlessly fascinating place. It was called the black kitchen because it was all wood-fired and soot covered the walls, but it was the hub of the home. It seemed like a huge place when I was five, but when I go back there now I see it’s so small. But so much went on in there. There were always a couple of house girls scraping coconuts, and my father’s two sisters and my grandmother running the whole show. Mum was never there because she had to look after my younger brother – the only one born in Sri Lanka – and she also became prone to tropical diseases, like dengue fever.

“We lived in a village where there was a market every Sunday out the front on our street, so I grew up surrounded by all this wonderful produce. There was no refrigeration anywhere in the house, so the day would start very early for the ladies, and I was always up then too. They had a little stool made for me and they would give me jobs to do. I was in awe of the way my grandmother would use the chilli grinding stone. She would make these colourful balls of curry paste – one colour for fish, one for meat and so on – and line them up above the stove. The daily ritual would begin with making the breakfast food, string hoppers, milk rice with left-over gravy from the day before, and always a beautiful sweet banana and something green for balance.”

Peter pauses again while the jackhammer does its thing, and Alba gets closer to reality. Without missing a beat, he continues his heartfelt story: “There were 22 people living in the compound, so my grandmother would assess the requirements of each of them, who would be staying at home, who had to go to work or school, and the general health of each of them. One of my first jobs of the day would be to sift through the rice for bits of rock, because the unscrupulous sellers would put a handful of granite in to get the weight up. Then, a bit later, my grandmother or the aunties would go to the market. Not the big one they had on Sundays but another smaller one behind the bus station which opened early every morning. After the markets had been done, we would start to prepare the hot lunches which a houseboy would later deliver to school. In the afternoon, the women would start preparing the dinner, which was at least five or six different curries, surrounded by leafy greens.

“I was good at making string hoppers. And I loved the festive occasions, when we’d make milk toffee and other sweets. I loved the ritual of everyone stirring it, so that we had all been a part of its creation. When I first started in the kitchen I had no taste for spice, so my grandmother taught me how to make snapper curry, which would get me to the next level of appreciation of spices, and that’s the recipe for a mild but fragrant curry that I’ve been using for the past 20 years.”

By the mid-1970s Sri Lanka was beginning to feel the strains that would ultimately lead to 25 years of civil war. Wickramapala started to talk about moving. Says Peter: “There was increasing political violence in Colombo and the government made it harder to run a business. It was time to go, so Dad sold everything for black market cash, which he converted into gold and gemstones and we just left the country. Coming to Australia was Mum’s call. Dad wanted to go back to London, but she said, no, let’s try something different. She’d read about Gough Whitlam getting elected and how he’d made visas easier to get for people with skills.”

Peter was 12, going on 13 when the Kuruvitas arrived in Sydney. He recalls: “Relatives and friends in Sri Lanka who’d never been there were telling us we wouldn’t be able to get anything once we arrived, so we landed with all kinds of stuff, including pockets full of gold and gemstones. I had gold bars taped down both arms. We got to customs and they started going through everything, even the jars of spices. It was only a matter of time before they found the gold and the gems, so Dad pulls out this jar of Maldive fish, petrified tuna, and it stinks. He shows the guy the jar and asks is this okay? The guy opens the lid and nearly passes out. We were hurriedly sent on our way out of the customs hall.”

After an uncertain start in Blacktown in Sydney’s west, the family settled in Mortdale, in Sutherland Shire. Says Peter: “I learned to surf at Cronulla and started barracking for St George. We ended up buying a house in Mortdale after Dad had a relative kick the squatters out and sold the house in Fulham. Now we were Aussies!”

But Peter and school did not make a good combination. He says: “I was quite good at it, but I wanted to leave as soon as I could, which was 15 and nine months. I used to get the cane a lot. One time I was sent home with a note in a sealed envelope for my parents. I handed it over to my father, and after a while, he gave me another sealed note and told me to take it back to the headmaster. I stood there while the headmaster read it and he started laughing. He asked me, ‘Do you know what this says? It says, give him six for me!’

“I’d spent a lot of my time in Australia fighting bullies and getting knocked down, so I’d started training in martial arts. I’d toughened up, but I’d lost a lot of that warmth I’d known from my kitchen life in Colombo. One day I was driving around Mortdale with Dad and he said out of the blue, ‘You used to love cooking with your grandmother. There’s a restaurant, why don’t you go in and ask for a job?’

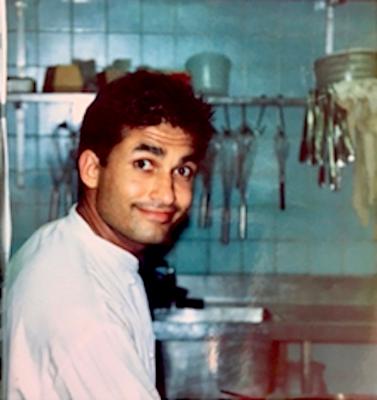

“I thought he was mad, but I knocked on the door and a young guy opened it. I told him my father had forced me to come and ask for a job. He said, ‘Good, we were thinking of looking for an apprentice’. It was a family restaurant called Crab Apple. They did French food which was basic but really good. This was just before dinner service began, so they handed me a knife and told me to make the garlic bread, so I did it very quickly – I’ve always been a fast worker in the kitchen – and they seemed impressed, so they hired me, starting that night!

“I ran out to the car where Dad was still waiting. I said, ‘I got a job dad, I’m an apprentice chef!’”

Next week, the making of a celebrity chef.