By Phil Jarratt

Guiding his tinnie across the 300-metre stretch of the Noosa River that leads to “Colloy”, the beautiful North Shore riverfront home he shares with partner Natalia, retired international businessman Nick Hluszko points out properties that suddenly people are willing to pay telephone numbers to buy.

“It’s crazy,” he says. “It wasn’t long ago that only a certain kind of person would even consider buying here. The wives considered it a difficult posting.”

Nick, whose significant business credentials – he worked around the world for Mobil and reinvented KFC in Russia – and his love of the river have led him to represent on the Noosa River Stakeholders Committee, first bought North Shore property back in 1984, when it was under threat from developers on several fronts. Digging around on his block opposite the new council chambers, he kept finding rusty pieces of machinery, and a little research revealed that a timber mill had once been there, along with the homes of the mill manager and Noosa Shire’s first chairman, James Duke.

A dozen years later, while working for Mobil in the US, he bought another riverfront shack and boathouse downriver, and when Mobil merged with Exxon, he “took a wheelbarrow to an ATM and came home”. Living in the shack, he started kicking around the property and after discovering boat parts and oil drums in shallow graves, he realised it had been a significant boatbuilding operation, and research revealed it had been the birthplace of early putt-putts for both T-Boats and O-Boats several decades before.

But Nick’s historical research stepped up to a new level when he returned from his Russian stint to retire on the river in 2017. Earlier research had led him to the name Colloy, possibly meaning shark in a Kabi Kabi dialect and once attached to the small run of workers’ cottages either side of the McGhie, Luya and Co timber depot and wharf, but he had no idea that the property on which he was about to build the dream retirement home, was at the epicentre of this forgotten village.

He recalls: “All the stuff about oysters was just starting to happen, and people were talking about the North Shore as a pristine wilderness that had never been built on. As I researched the history of my block, I started photocopying titles of property and discovered this Abraham Luya who had purchased 84 acres of riverfront in 1872 for 21 pounds. Up to the turn of the century this area was pretty much commercial, and then the downturn of the timber industry here when it was pretty much lights off.”

Nick presented his well-researched findings to Noosa Council, where they have recently found a home at the new Heritage Noosa website (heritage.noosa.qld.gov.au), including site plans and extracts from contemporary newspaper reports describing the McGhie, Luya facility and the workers’ village surrounding it.

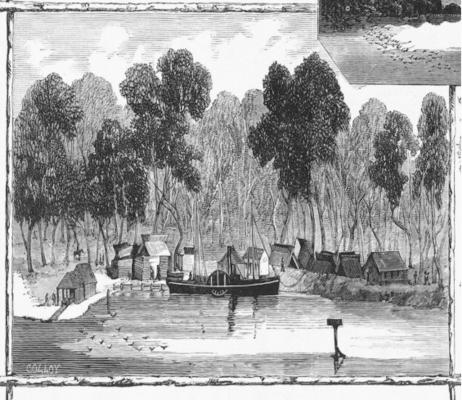

My own research for a new history of Noosa, Place of Shadows, due in July, found that the timber depot was a bigger operation than lithographs depict, with the company steamer

Culgoa transporting some 35,000 feet of timber each trip to Brisbane and making three trips a fortnight. The company had over 150 men at work cutting and loading, which boys’ town aspect might have had something to do with why no pioneer tourists or journalists seemed to visit Colloy.

Certainly the male domain across the water contributed to the wild reputation Tewantin had, as on many nights the streets teemed with men looking for respite from the hard work of the day. Lonely sawyers and wharf labourers would row across from the McGhie, Luya loading docks, looking for relief of one sort or another. After the drunken binges and sexual excesses of Christmas 1872, the authorities increased policing and Tewantin became more civilised, but by the time this was achieved, little Colloy across the river was in rapid decline.

The cottages became fishing shacks and gradually disintegrated from neglect, but as the tourist trade increased after World War II, the early hire boats were built and repaired around what remained of the McGhie, Luya wharf. In his yard and garage at Colloy, Nick Hluszko has many found objects from those years, but his favourite is the old O-Boat putt-putt renamed the Kenny Bill, by an old crooner turned fisherman named Kenny Maguire, which Nick bought from the family after Kenny’s death.

Over Kenny’s nameplate is an image of a 1940s microphone, a small hint of a forgotten past, much like what remains of the village of Colloy itself.

Visit heritage.noosa.qld.gov.au to find more about Colloy and other aspects of Noosa’s fascinating history. Place of Shadows, The History of Noosa, will be published by Boolarong Press in July.