For more than 40 years now, since Indonesia’s develop-or-perish Suharto government began its hotel-building pillage of Bali, the little Island of the Gods so close to our northern shores has teetered between economic basket case, environmental disaster and miracle of recovery.

Sometimes it’s been all three at once, and now might be one of those, but certainly the quarter century since the Asian currency crisis finally saw off the tyrant Suharto, it’s been a never-ending cycle of boom and bust, with tourism replacing small cropping as the island’s only real industry, tourism being destroyed by the terrorist attacks of 2002, tourism making a miraculous comeback by 2004 only to be shot down again by the Jimbaran bombings in 2005, tourism surviving the GFC and entering a new Euro-Asian boom driven by Chinese and Russian investment, only to be shot down by Covid in 2020 and then rise again from its funeral pyre over the past 18 months… and so the cycle goes.

There are many sometimes sad but often also uplifting human stories from this roller-coaster ride, which we’ll get too in a minute, but to understand what’s been happening these past few years, it’s instructive to look at the economics.

In January 2020 the World Bank reported that Indonesia was officially middle class, with one in five Indonesians (more than 52 million) “economically secure”, thanks to 50 years of sustaining an average annual growth rate of GDP of 5.6 per cent.

While this was unlikely to be of comfort, should they have known, to the multiple millions living in rural poverty up and down the archipelago, the World Bank noted that “of those who were poor in 1993, 80 per cent were no longer so in 2014”.

You can cut these numbers any way you like, but the fact remains that the gap between rich and poor across Indonesia remains ludicrously wide. And Bali, Jakarta’s capitalist cash cow, was in total Covid lockdown just two months later, with more than half a million hospitality workers sent home, sans safety net, to tend the fields they no longer have because tourist accommodations were built on top of them.

There is no doubt that Bali was an economic and social basket case in 2020 and 2021, with many families who owed their living to tourism struggling to put food on the table, while Indonesia as a whole was hurriedly bracketed down to “lower middle income”.

Yet a mere two years after the World Bank announcement, Indonesia’s Minister of Trade, Muhammad Lutfi, in a virtual media conference on Wednesday 23 February 2022 (virtual since many parts of the country, including all of Bali, were still in lockdown) was able to announce that Indonesia had been classified as an upper-middle-income country.

“Today we have officially become a world middle class country,” he said.

Again.

And indeed by the end of 2022, the world leaders attending the glittering G20 meetings in Bali, wearing their obligatory batik shirts and stuffing down the satays and rendang poolside, must have thought they were sharing in the dividends of yet another economic miracle, while the images flashed around the world.

But it’s interesting to browse the Bali Leader’s Declaration tabled at the G20, which says in part: “We reaffirm our commitment … to close the gaps in energy access and to eradicate energy poverty … guided by the Bali Compact and the Bali Energy Transition Roadmap, we are committed to finding solutions to achieve energy markets stability, transparency, and affordability. We will accelerate transitions and achieve our climate objectives by strengthening energy supply chain and energy security, and diversifying energy mixes and systems. We will rapidly scale up the deployment of zero and low emission power generation, including renewable energy resources, and measures to enhance energy efficiency, abatement technologies as well as removal technologies, taking into account national circumstances.”

Nice ideas, but note the get-out clause of “national circumstances”.

This, after all, is an island where piles of plastic burn by the roadside every sunset despite some excellent citizen campaigns in recent years, where for decades you could overturn a green belt designation if you had the money (and it is rumoured you still can), where massive hotels are built at the end of two-lane tracks with no footpaths and no other access, and rice fields continue to disappear at an alarming rate, the sophisticated subak irrigation systems with them.

To be true to their declaration, the leaders of Bali would need to completely change the mindset of everyone involved in tourism, housing and industrial development on the island, and there is little sign of this happening.

But there is always hope for a return to kerta yuga.

Which brings us back to the human side of this.

Some readers may recall in these pages a year ago being introduced to my young friend Wayan Agus Parwita, “the man who saved a village”. There are many Bali stories like his, but I know and love Wayan’s the best, so here it is in brief.

In the mid-1960s, when Sukarno’s “Gestapu” bloodbath was spreading across Bali like a bushfire (eventually claiming more than 80,000 lives), Wayan’s grandfather died unexpectedly, leaving his father, I Nyoman Suwita, then 14 and at school, to kill eels in the rice-field canals at night to feed the family and sell to neighbours. Somehow Nyoman managed to stay at school long enough to complete a woodworking course and became a talented sculptor of temple buildings, chasing the work to Java for better money.

But as tourism began to saturate Bali in the ‘80s, Nyoman discovered there was more money to be had sitting in the lobby of a hotel carving toys and souvenirs.

One of Wayan Agus’s first memories is sitting on the tiled floor with his dad, helping sweep up the wood shavings while Nyoman negotiated a price for his works, which he was good at, making enough to buy motorbikes to rent and later to send Wayan and his younger brother to Udayana University.

Armed with a hospitality degree, Wayan was working as an assistant manager at a restaurant just around the corner from the Sari Club the night the bombs went off in Kuta.

Saved from injury or even death by an early mark due to a Japanese wedding finishing earlier than expected, Wayan was still out of a job, like the rest of Bali. In the family tradition, he found work as a cabin boy on the cruise ships, plying the Caribbean routes and sending every pay cheque home.

When he finally came home, it was for the love of Made, now his beautiful wife.

He worked as a driver for tourists and expats, and slowly became their guide through the many pitfalls of villa construction.

When I first met him back then, I was so impressed by his energy, enthusiasm and grasp of all kinds of situations, that I borrowed him from the employ of an Australian friend to act as my driver, interpreter and cultural guru while I researched a book about Bali. Thus began a friendship that has never faltered.

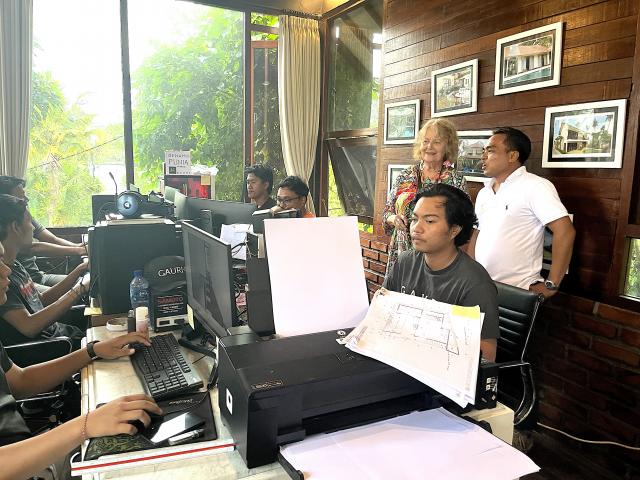

Come Covid and Wayan had established himself through his fast-growing company, Kori Dewata Karya, as a savvy project manager focused on sustainable development. With the traditional Javanese labour force locked out of the island, Wayan saw a way to provide employment for his home village of Cepaka, where virtually everyone had lost their hotel jobs. In the end he found 800 jobs to help them through the pandemic, and he is still creating work for them.

A deserving hometown hero, he is now developing eco-friendly villas and small businesses in Cepaka, and by the end of the year will have 40 projects on his books with 30 staff and up to 300 contractors at any one time. And he has also found time to establish a community bank in the year between my visits.

From dad catching eels to survive to son a prominent businessman providing for his community in just one generation – you can’t help but be impressed.

With a flying business trip to Singapore in the middle of it, and three kids on school holidays, Wayan and Made didn’t see much of us this trip, but they did take us out to a splendid dinner, Kori Dewata’s shout. Over fresh fish and pork satays and plenty of wine, Wayan told me about the local produce restaurant he will soon start building as the centrepiece of his riverside villas in Cepaka. It sounded wonderful.

I told him: “This time next year it’ll be 50 years since I first came to Bali. I want to book the restaurant out for a family celebration. Can you be ready?”

He offered a knuckle and I bumped it.

“Consider it booked, Pak,” he laughed.