It’s every surfer’s worst nightmare. One overcast afternoon 20 months ago, it was suddenly Wolfgang “Wolfie” Noga’s reality.

We are sitting in the shade in the Noosa National Park, sipping coffee after a pleasant surf session at Tea Tree, where it all went pear-shaped in 2019. When I ask Wolfie, now 71, to tell me about the accident, he hesitates, the emotions of his near-death experience perhaps still too raw. But then he jumps in, just like he did that day.

“I got out to Tea Tree much later than normal and pulled this beautiful five-foot-four hollow wooden board with a foil bottom out of the bushes. (Wolfie has been leaving his surfboards hidden in the park for nearly 40 years.) I just loved that board, it fair flew. So, I’m out on the jump-off rock and there were a lot of longboarders on the takeoff, and I thought I’m not going to get a wave out there. I looked out the front of the point beyond them and it looked deadly. The week before I’d lost a couple of fins out there, so the writing was on the wall, and for a moment I thought I should turn around and go home. But I’ve never done that in my life, so I just jumped in and paddled into the zone.

“A set came and I took off, made the drop and the bottom fell out of the wave. The fins just scraped the bottom and the board stopped dead. I got catapulted forward and face-planted on the ledge – broke my nose, broke my neck, tore the ligaments off my spine, dislocated my shoulder, broke all my ribs, broke my knee. I was semi-conscious in the water but I lost control of my body. I couldn’t push up, my legs wouldn’t work, I was having difficulty breathing and I thought I was going to die. Then a guy paddling by saw the board and pulled me up by the legrope. He’d been a paramedic so he knew what to do. He carried me up onto the rock ledge and started giving me mouth to mouth. Apparently, all this water and sand and seaweed gushed up and I came to and sat up and started telling jokes. I can’t remember any of it.”

A medivac helicopter rushed him to Sunshine Coast University Hospital where he was put in an induced coma. He recalls: “When I came to I had tubes coming out of everything. I couldn’t move any part of my body and they told me that my situation was bad and getting worse – I could be paraplegic or brain dead, or just plain dead.”

Fourteen days later Wolfie walked out of hospital unassisted. He puts it down to the wound healing properties of comfrey and a positive attitude. His surgeons called it a minor miracle. Either way, he owes his life to them and to a fast-thinking personal trainer named Angus.

He was little Wolfgang Gadd when the family arrived at the Fairy Meadow Migrant Hostel near Wollongong in 1955, the name having been changed from the Hebrew Noga for protection in wartime Germany. Charlie Gadd had been a teacher but his qualifications were not accepted, so he went off to the coal mines like everyone else and studied at night. (A decade later he would be my high school maths teacher.)

The Gadds lived surrounded by snakes, lizards and kangaroos on a dense battle-axe bush block halfway up the Illawarra escarpment at Wombarra. When bush fires raged through the area they were given one instruction: If the house catches fire, jump in the creek.

Wolfie learned to swim at the Wombarra tidal rock pool. He recalls: “It was kind of a crash course. The big kids threw the little kids in the deep end.” Later they moved to a house a block back from the beach at Thirroul, and Wolfie joined the surf club and learned to surf on borrowed boards. One of the older boys had an FJ Holden and he’d drive them to nearby Sandon Point’s quality point waves for threepence a head, the catch being that he’d only leave when he had five paying passengers. “We’d have to sit there in the sun for an hour or more, watching these perfect waves go unridden at the other end of the bay,” Wolfie remembers.

When he left school, Wolfie Noga (he’d changed his name back) lied about his age and got a job as a crane chaser with the water board. Earning adult pay, he soon saved enough to head for the surfing nirvana of Byron Bay, where he rode waves every day until the money ran out, then headed south again and hooked up with some abalone divers at Mallacoota. He fleeced them at poker to the tune of $1700 that first night in the campground, but they gave him a job anyway, ushering in a period of prosperity that saw him work the abalone grounds from Flinders Island in Bass Strait to Esperance, WA.

He says: “Esperance was full of divers with missing limbs from meeting white pointers. I rather like my limbs so eventually I headed north, ending up in the Abrolhos Islands, where I rented a fishing shack and started a family with my girlfriend, Kerrie.”

Kerrie’s family was in Brisbane, and on a trip back east to see them, the couple fell in love with the Sunshine Coast, bought a block at Mount Coolum and Wolfie bluffed his way into a job as a stonemason. About now we begin to see a pattern emerging in Wolfie’s life – he travels to the beat of his own drum, and the normal rules of engagement don’t necessarily apply. After a stint working a quarry at Coraki and selling the stone to Byron Bay – “too many dodgy characters down there” – Wolfie got a licence to take stratified stone out of a council quarry at Pomona. He took samples to all the stonemasons he knew in Brisbane, then took their orders to a finance company and got a loan to buy a tip-truck.

“My career as a quarryman began, just like The Beatles,” he quips, in one of the obscure cultural references that punctuate his conversation, this one a nod to Lennon and McCartney’s first band.

When that quarry closed, he found a slate deposit on mining land near Gympie, and set up house in a nearby cave. The mining inspector explained that his lease did not include the right to live on site. “I’m not living here,” Wolfie retorted. “Living is what I do in Noosa. Here I’m just existing between work spells.” The matter went to court where, according to Wolfie, the magistrate sided with this quite reasonable premise.

Around this time, the relationship with Kerrie ended, he took up with a Gympie girl, they pooled their savings and bought a farm and Wolfie started a second family. He also started hiding his surfboards in the National Park, to make it easier to squeeze in a quick surf on his slate-selling missions to Noosa.

Over the decades that followed Wolfie divided his time between stonemasonry and trucking stone from the quarries, while watching relationships come and go and fostering his solitary passion for organic living, stripping away all but the essentials of life, which include some good surfboards, a weekly case of stout and an electric bike, which came into the equation when he turned 65 and a shoulder injury forced him to retire from stonework. He bought the parts, made his own version of an e-bike that “goes like the clappers” and pedalled around Tasmania.

Since then, apart from time out to recover from the surfing accident, Wolfie’s life has revolved around enriching the microbe content of the soil at his hinterland property using biochar, growing his own healthy food and pedalling to the beach at first light to pull his board from the undergrowth and surf his beloved outer bays.

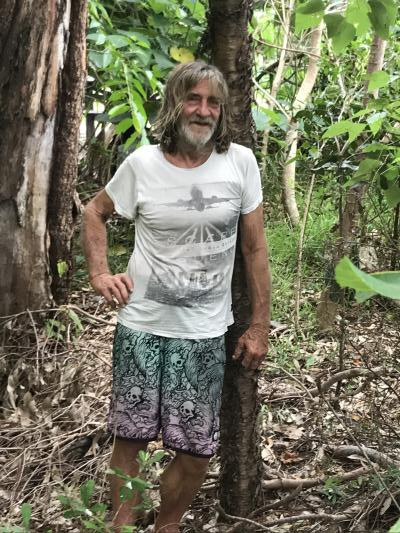

I heard about Wolfie through a mutual friend and immediately wanted to interview him, but it wasn’t easy. He has no phone and no computer. He lives in the hinterland but few people seemed to know where. “He surfs until about 10am most days,” the friend said. “You just have to be there when he picks up his bike.” But I didn’t know what he looked like, although I figured I must have surfed alongside him over the years. The friend thought about that before responding. “He’s pretty fit but he looks like he’s had a hard life.”

After a week of near misses, I gave up on Wolfie last week and went surfing instead. As I paddled into the line-up at Tea Tree, the friend pointed at a bedraggled figure in a tee shirt sitting on his board up the line a bit. I paddled over and introduced myself, and made the right noises about his brand-new, camouflage-patterned nine footer. “No one will ever find this one,” he shouted over the roar of an incoming wave, which he surfed steadily, if a little tentatively, still a bit rock-shy.

“Do you remember Charlie Gadd?” Wolfie asked when was back in the line-up. “Yes, I do. Great teacher, great mentor,” which may have been laying it on a tad thick, but we were good to go. Let the interview begin.