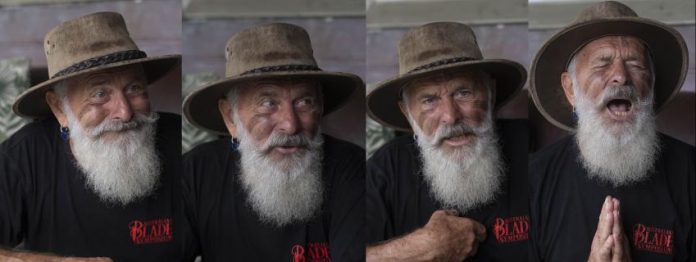

Having become disillusioned with Noosa, artist and blacksmith Steve Weis last Sunday auctioned everything to walk away from the Kin Kin property he transformed from an industrial storage site to a work of art after it became his sanctuary 25 years ago when he was “spiritually devastated“.

Auctioneer Richard Hansen described the artist as “an absolute legend in the game“ before Steve opened the auction to shed more than two decades of creative endeavour, along with his tools of the trade.

“There are a lot of reasons this auctions happened – some of them are age-related, some accident-related some emotional, some political, some global – all together there are enough reasons to be selling everything off,“ Steve said.

“I hope you enjoy 25 years doing the best I could to make a difference in this world.

“May you bid with courage and spirit and may you get something you spend the rest of your life grateful for having.“

As the auction proceeded Steve told Noosa Today more about his time in Noosa.

“My life’s been a rough rollercoaster,“ he said.

“My first two wives died, the first one from Avian (Hong Kong) flu, the second one died from breast cancer. Then I had a marriage on the rebound that offered me the opportunity to be the latest arty-farty superstar in New York. I just wasn’t ready for it and I walked out and that was devastating.“

Filled with unresolved grief Steve searched for a place to heal, finding a property just outside the town of Kin Kin. It was an “industrial mess“, owned by a hoarder.

“I was spiritually devastated. I said if you can clean this up you may save yourself.“

Having spent hours just visualising the world he was going to create, over the next two decades Steve achieved his goal – “absolutely“.

“My pieces all hold spiritual determinations,“ he said.

He’s created some of the most historic and remarkable pieces of art metal around the region. Steve’s artworks adorn sites across the country and internationally and his Kin Kin property has long been a place of wonder for its many visitors.

“The best part of it was making it. I’ve loved doing it,“ he said.

Steve defines his art pieces, many large in scale and filled with musical elements, as being driven by “spiritual conscience“.

“Some people say I’ve got small man complex. but I do like big, I like scale. I like magnificence. I like to have the feeling there’s something bigger than us,“ he said.

“By nature I’m a mystic.

“My father used to say I don’t know where you come from, you’re definitely not one of us.“

Steve had little formal art education.

“I did six Saturday mornings of adult education training then started my career on the seventh day,“ he said, with the inspiration for his work coming from the “spirit dimension“.

“At a knife convention they told me every knife I made is unique, they said your knives all have a soul,

“That’s where I start, I go into the workshop.

“I call out to the infinite to bring me an activity of creation in the form of a knife to invest this day in.

“I call it down. Then I wander around the place and say which pieces of steel want to be in this Damascus lamination I’m going to make.

“They said this is the strangest process we’ve ever heard, but it makes sense.

“And I said the moment you start doing it, it’ll start working for you. It’s a method you’re not going to learn in a university.

“It’s the sort of method you’d learn if you worked with any indigenous Elder in any culture in the world.“

Over the decades his art base has captured the imagination of many.

“I’ve showed thousands of people through and told them the deeper inner stories of it,“ he said.

“I showed councillors through. They said, how do you do this with all the quarry noise?

“I said it’s completely devastating. And they said it must be. And nothing happened, and I felt patronised. I voted for these people and I felt betrayed.

“I have financed this, I’ve gifted this and received nothing in return.

“The lack of respect, the lack of gratitude the lack of acknowledgement just got to a point that I said the work of continuing and maintaining this with no recognition and response, no protection, no kindness is more than I’m willing to bear.“

Steve said the disruption to his life caused by the operations of the Kin Kin quarry were part of his reason for leaving.

“The quarry, my disappointment in Noosa Council poor performance in protecting the people of the hinterland.

“I’m 2km from it, 288 quarry trucks a day on a big day, starting at 5.15 in the morning, six days a week for many years.

“I’ve been in the protest, went to the court, done affidavits, Judge Long is still deliberating after 18 months.

“Noosa Council have not responded to notices given by the community about many, many breaches, never once stopped the quarry, made them accountable.

“I’m so completely disappointed that Noosa with its biosphere and with its marketing seems to have missed the point and seems to be so gloating in its financial superiority.

“My gift has been received by a few and overlooked by the institution and in that regard they no longer deserve me.“

Steve’s health has also been a cause of his departure.

“I tripped and I fell. I crashed my forehead very badly. I got a serious concussion, four months I had a concussion, had to have X-rays and ultrasounds they told me this isn’t your first brain injury. They told me no heavy lifting for a year,“ he said.

“I didn’t go into the workshop for a year. Then I got a flu, got pneumonia, thought it was a good time to stop welding.“

After what has been an emotional past five years he describes as “devastatingly agonising“ Steve and his partner have bought a house at Woodgate Beach, ready to begin the next stage in life, and maybe write a book.

“To be at this moment when it’s coming to an end, there’s some relief to it,“ he said.

“I’m lucky I’m surrounded by people who adore me. I’ve earned it. I’ve stayed loyal to my heart, loyal to my creativity, my imagination, loyal to my friends.

“I’m going to Woodgate to walk along the beach, do some meditative breathing, try to heal, let go, purify.

“If it goes the way I’m imagining I might put myself in a very quiet place and write a book of spiritual lessons, a memoir.“

His intended title brings together his philosophy on life and a page from his childhood – ’Holy sufferance, diary of a dingbat’.

“If you live the truth of your heart you will suffer, humanity works on other things it’s about money, control, power, if we live truly by our heart we end up being a kind of an oddball,“ he explained.

“Because it has to feel everything it’s a path of suffering. All the saints and mystics and all the great stories of great courageous spiritual souls live by the heart and accept that suffering is the price.

The sub-heading of his book comes from something his father would “regularly“ say, “you’d have to be a bloody dingbat“.

“This isn’t everybody’s language of life but it’s the one that fits my experience of it.“