While many people know that the postwar pioneers of modern Noosa were fishermen and surfers, always looking for schooling fish and better waves around that next headland, what is not so well known is the strange relationship that developed between the town and the surfing community throughout the 1960s.

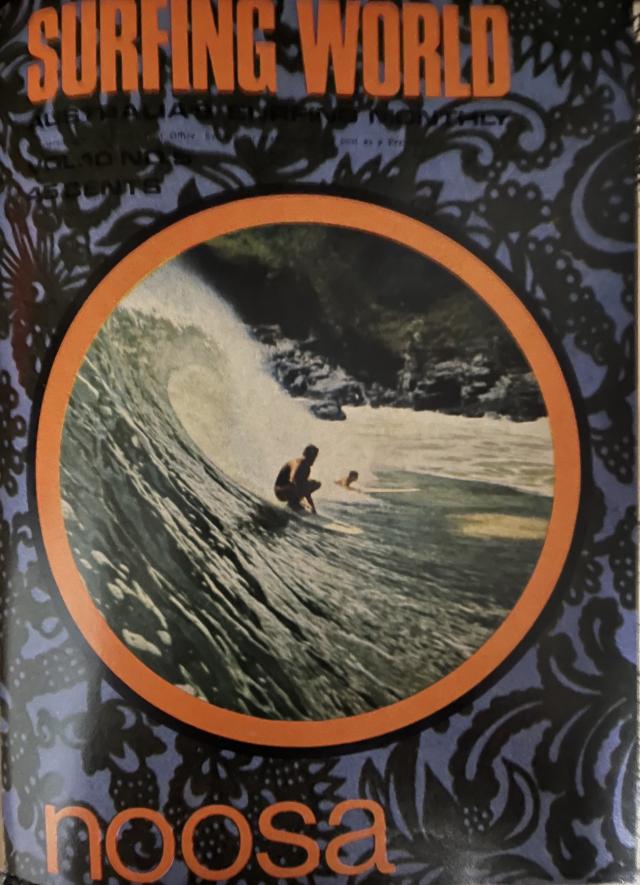

First it was a secret, then it was a northern Nirvana and surfing its points was “like having a cup of tea with God”, and by 1968 the question was being asked “Is Noosa dead?” even as surf magazines devoted entire issues to illustrating that the answer was, well, not quite.

When I first surfed the points more than 50 years ago on the tail of a cyclone, First Point and the Boiling Pot were as crowded as the northern beaches of Sydney where I’d driven from, yet a friend and I surfed wild and bumpy Granite Bay almost to ourselves, and I fell head and heels in love, eventually making Noosa my home 20 years later.

Having forsaken my own substantial surf magazine collection in the interest of downsizing a couple of years ago, I’ve lately been reacquainting myself with this forgotten side of Noosa history through the remarkable Al Hunt Collection of more than 20,000 magazines and books, now housed in the reading rooms of the Noosa Surf Museum. It required a bit of digging, sometimes getting sidetracked by the discovery of my own articles I’d forgotten ever writing, but I managed to track the main parts of the story.

The first article published about surfing on the Sunshine Coast, Notes From The North, appeared in the fifth issue of Surfing World magazine in January 1963, submitted by “Queensland surfer-photographer Chick Graham” who failed to give Noosa a mention, perhaps intentionally. “I find the boys are now occasionally riding the Point Cartwright killers,” Chick revealed, alongside a few photos of straight-handers and ugly wipeouts. “The waves here are really murder but they keep rolling when they won’t roll in other spots.”

My own surfing journey was just beginning that summer, so I’m not sure if surfers actually spoke like Chick, but I somehow doubt it.

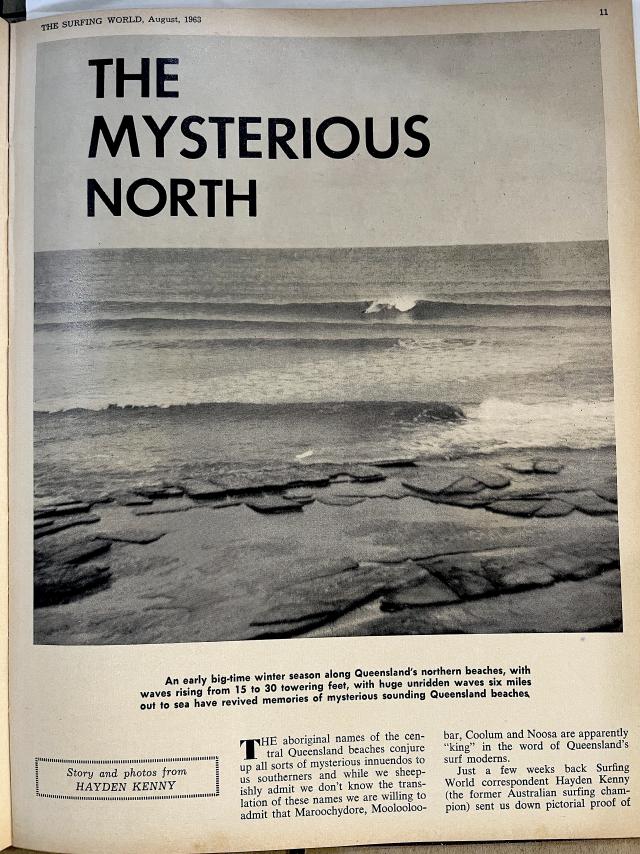

Noosa fared somewhat better (or maybe worse) six months later when Surfing World Vol 2 #6, published in August 1963, included an article titled The Mysterious North, in which SW correspondent Hayden Kenny barely mentioned us by name but featured a lineup shot of “Tea Tree Bay, Noosa, yet another great Queensland surfing spot”, with easily the best waves in the coverage. This may have been a case of Kenny, who had been riding the Noosa point waves in splendid solitude since the late 1950s, being coy about revealing the location. But editor Bob Evans’s expansive caption blew a hole in that.

In fact it was the long-departed Evo, also a one-man surf film factory, who really put Noosa on the map with his 1967 offering, High On A Cool Wave, which featured world champion Nat Young and surfboard shaper Bob McTavish using the Noosa points as a research and development centre in preparation for the 1966 world titles. By this time secret Noosa was well and truly outed, but in 1968 Evo reflected on happier times:

“At the end of May 1964 I drove north from Sydney with the specific purpose of finding out about Noosa. The bays looked just as I’d first seen them, shimmering in the autumn sun, sloping tree-clad foreshores reflecting vividly in the mirror of the quietest and calmest ocean. At that time estate agents had no argument with surfboarders, and my enquiries soon had me directed to an apartment on the hillside between Main Beach and Johnsons. From any point in the house I was able to watch the ocean, the schooling tuna leaping in their sunrise exhilaration, feeling the slight chill of an early morning westerly, through to the daily glass-out as the breeze turned to the south-east.”

That trip had provided the substance of the first major coverage of Noosa, published in the September 1964 edition of Surfing World. Having received a batch of exciting photos of a good autumn swell from photographer Mal Sutherland, Evo, accompanied by young emerging photographer Albe Falzon and Californian surfer-shaper Bob Cooper, struck out for the mysterious north, but they had left their run a bit late in the season for quality swells, and had to rely on Sutherland’s photos.

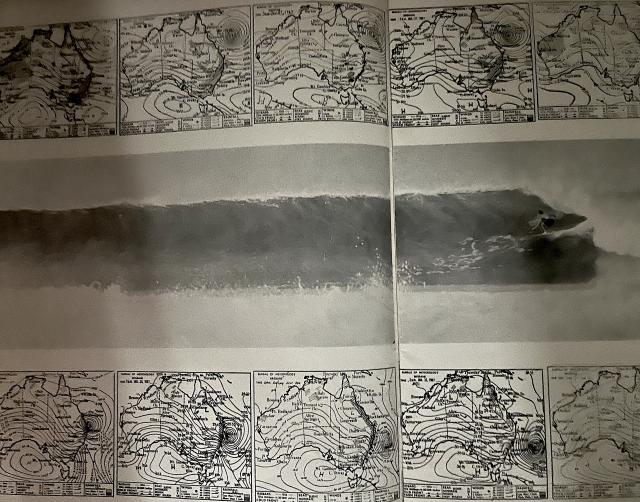

The next time Surfing World went overboard about Noosa’s charms, they didn’t just catch any old swell – they caught Cyclone Dinah, still regarded as one of the truly epic swell events in Noosa’s history. For the March 1967 issue, new editor John Witzig organized a cover photo of a group of surfers, himself and Bob McTavish included, looking hippie-ish and vaguely threatening (or stoned!) in the National Park undergrowth. The 20-page cover story was titled The Wild and Wonderful Days of Noosa, but the opening article, by surf-crazed Dr Robert Spence, avoided the hippie blah and stuck to the facts. It began:

“A call from Noosa, collect. Will you take it? This is my secretary on the intercom. Nothing special about collect, but Noosa, priority. Put the call through. The surf here is rising, there’s a cyclone out at sea heading our way. You coming?”

Hell yeah!

But Bob McTavish’s bliss attack could not be contained: “The North is ultimate summer in Technicolor. It rains up here too… The waves of National Park are the best things I know in surfing. Riding them is second best. What is a National wave? A series of incidents that add up to a tale of being. One minute a pressure, then a cruise of ease, next a calculus, and finally, always finally, satisfaction.”

Noosa was back on the Surfing World cover with the line, “The most wonderful wave in the world” in 1968 for a special issue with 30 inside pages devoted to our breaks and the Noosa beach lifestyle. Half a dozen surfers and writers had a go at describing it, but the best of them was local surf girl Lynn Jones, in a piece she called, When Noosa calls, answer it”.

“Countless are the times I’ve seen happy people, happy because they’ve found the perfect wave. It’s a weekday as the tiny lines push across the four bays at Noosa and you can feel a friendliness amongst the different bodies of surfers in Noosa, some seeing the place for the first time, others making another trip to renew their Noosa experience and prove it was no hallucination… Perhaps the best time you can experience in Noosa is when the day is almost over, you’ve surfed until your mind thinks only of wave upon wave, and although you’re greedy as you enter the water for a final session at Main Beach when it’s almost dusk, the waves are so hollow all the strength you thought you’d lost reappears to burn to its end.”

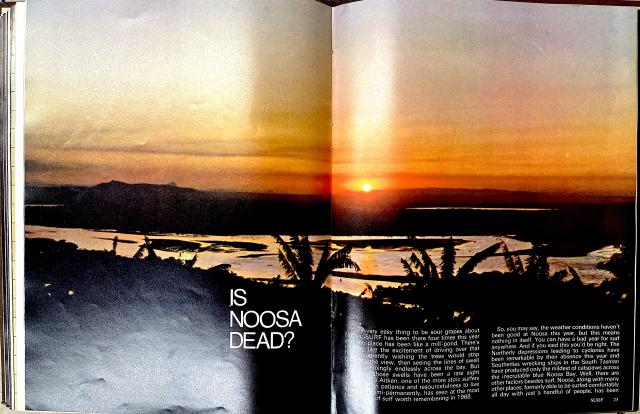

By now Noosa was crowded for every major swell event, but with swell forecasting virtually non-existent, if it didn’t make the nightly news it wasn’t happening, and quite a few medium swells were left to locals only. But there was bound to be kickback sooner or later, and it came later in 1968 when Surfing World rival Surf International published a multi-page whine called Is Noosa Dead?

The uncredited author began: “It’s a very easy thing to be sour grapes about Noosa. Surf [magazine] has been there four times this year and the place has been like a mill-pond… Bob Aitken, one of the more stoic surfers with the patience and resourcefulness to live there semi-permanently, has seen at most two periods of surf worth remembering in 1968… Noosa, along with many other places formerly able to be surfed comfortably all day with just a handful of people, has been inundated with crowds…”

But it wasn’t just the mill-pond of Laguna Bay that irked the writer: “Noosa is full of expensive cars, of charming, well-spoken elderly couples, often still elegant, strolling along the walks of National Park accompanied by a bitchy, neurotic Pekingese dog. Not only is this crowd welcome as the landlord’s prayer – no breaking open of the coin TV boxes [remember them?]… no Jimi Hendrix Experience thundering into the star-laden Noosa night.”

While this brilliant evocation possibly inspired the later creation of Noosa Waters, the writer must have felt that overall he’d gone a bit hard, adding a footnote of recognition for Dr Arthur Harrold and the Noosa Parks Association pioneers: “It was only due to the efforts of a small group of dedicated people that a large road lined by houses does not now exist along the foreshore between National Park and Sunshine Beach.”

Things went a bit quiet in the 1970s, with surfing’s transition to shorter boards making the breaks of the Gold Coast now the focus, but in March 1980, Tracks magazine ran a short article with no photos that lamented Noosa’s growth spurt and crowded waves. The headline really said it all: NOO$A.