In this, the second and final part of Tony Wellington’s vinyl dreaming, the two old boomers discuss over-amplification (Over what? Speak up, can’t hear you!), early Oz rock, presentism, wokeism and some very bad behaviour and rock’s uncertain AI future. PHIL JARRATT reports.

NT: You write about the Grateful Dead pioneering the use of Bob Heil’s revolutionary concert sound systems so we could actually hear the music, as opposed to Beatles concerts of a few years earlier where audiences struggled to hear anything above the screaming. But by the end of the decade with the rise of heavy metal it was often deafening. Did the amplification go too far?

TW: Well, the punks thought so because the notion of big stadium rock, with the artist so removed from the audience that there was no interaction between the two, was something they rebelled against. Heavy metal certainly took it as far as it could go, with extremely loud music performed in vacuous places with big light shows to make up for the lack of reaction between audience and performer. Punk reduced it down to venues like CBGB, which was the size of your average lounge room and Debbie Harry was right there an arm-length away. But going back to Bob Heil, at Woodstock in 1969 the people way up the back were hearing the sound from the side amps out of synch, whereas Heil’s system, which first attracted attention during 1970 US tours of the Grateful Dead and then The Who, delayed the main sound to the distant speakers by microseconds so that it all sounded normal. Suddenly huge auditoriums and outdoor concerts could offer good quality sound.

NT: In the book’s coda you talk about “presentism”, which made me go back to the very early pages in Vinyl Dreams where you describe the Kinks’ song Lola as the “first major international hit with a non-binary theme”, which seems a concept very much of the present. Can you explain presentism?

TW: It’s a delicate balancing act because I know the reader will be judging what I’m presenting by today’s standards, which may not have been the standards of the era I’m writing about. I was trying to avoid being too judgmental in terms of today’s standards. The other thing about that is artists of the era tend to explain their behaviour by saying everyone was doing it, which is not true. Or they’ll say, but we didn’t know about that back then, which is not true either. Chuck Berry was jailed in 1959 for having sex with a 14-year-old, so by the ‘70s everyone knew that you couldn’t do that. Debbie Harry says everyone was doing drugs at the time so she did too. But there were plenty of artists of the time who didn’t, like Frank Zappa and Bruce Springsteen, for example. Overall, I think there are several behavioural ideas that haven’t changed much over the years since the ‘70s, and one of them is older people taking advantage of younger people.

NT: I agree with that but what has changed is how we express those beliefs in the age of wokeism.

TW: Absolutely.

NT: Were you worried about wokes when you wrote the book?

TW: (Laughs) Not for a single second, but I was acutely aware of cultural mores of today and how they would interpret the book.

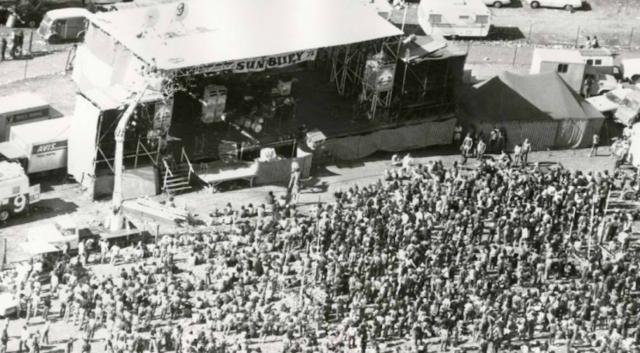

NT: You mention the Pilgrimage for Pop at Ourimbah in 1970 as the first big Australian rock festival …

TW: Yes, and I know Jackie [Phil’s wife] was there!

NT: Well, more than that, she was married to the keyboards player of the Nutwood Rug Band who organised the festival, but that band doesn’t make it onto the playlist.

TW: Ah, but I didn’t write about their songs, so they don’t make it onto the list. That’s the way it works. I also wrote about Tully but not their songs, other than in connection with them playing on Peter Sculthorpe’s Love 200 which did make it on the playlist.

NT: You note in the book that Peter Sculthorpe didn’t think much of Tully whereas jazz player Johnny Sangster thought they were the best band in the world. I’m kind of in the middle on that.

TW: But it was groundbreaking music at the time though. Free improvisation, which was Tully’s staple, wasn’t in the rock arsenal then.

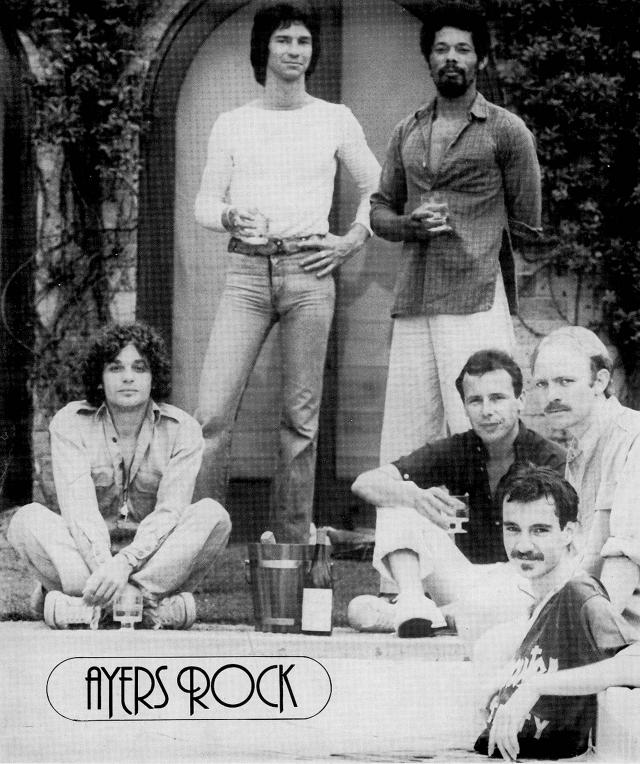

NT: I get the impression you weren’t a Skyhooks fan and yet you rave about Ayers Rock, a band I’d almost forgotten about.

TW: Ayers Rock was a jazz fusion band which was rare in Australia then, whereas Skyhooks was a pop band pitched at the Top 40, albeit with an irreverent streak attached. What they did was perfectly fine for its day, notwithstanding some of the sexism in their lyrics. But you’re right about history overlooking Ayers Rock, and that’s one of the reasons I wanted to highlight bands like that. In terms of the quality of their music, Ayers Rock were right up there, and they were the first Australian band to sign with an American recording label, so they helped pave the way for Little River Band and others.

NT: In the coda, you summarise the 1970s as “the most innovative period in the history of popular music”. That’s a big call, isn’t it? Particularly if you’re going to write the ‘80s next!

TW: (Laughs) I’m suggesting that it provided the framework for all the genres that came after, in terms of styling, rhythmic structure and everything else. After the ‘70s everything tends to be split into subgenres, like heavy metal becomes grind, core, American prog metal and so on. Yes, rock music has continued to expand and diversify, but what I’m suggesting is it’s hard to think of anything post-New Romantics that was as highly original as what was happening in the ‘70s.

NT: Is there another book in the ‘80s?

TW: Not at this point, but what happened was MTV took over and looks became more important than the music, glam writ large. Researchers have found that by the time we reach 30 we stop listening to new music and spend the rest of our lives listening to the music of our teens and 20s, because they were our formative influences. So we have to be mindful of the fact that there are people who were born in the ‘80s who think that the music of the ‘90s and 2000s was the pinnacle of musical achievement because that’s what resonates for them. I’m trying to suggest that it’s not just my age that makes me think the ‘70s so interesting, but also the climate of the era and the technological innovations.

NT: I guess there’s also the case that less is more. When we had less music to choose from we valued it more.

TW: Yes, and we put more effort into listening to music. You had to go to a shop and buy an LP for a lot of money and then go to the trouble of putting it on a turntable, so you were more invested in it. Now it’s like turning on a tap, so I think across the culture, popular music has been devalued. And today when you stream music you don’t get to find out much about who’s playing it. There’s no fold-out cover. Another big shift is that in the ‘60s and ‘70s music was a shared experience, sometimes forcibly shared with the neighbours! I’m sure it was the same for you, but my friends and I used to sit down in a room purely for the purpose of listening to a record.

NT: Oh yeah, the new Blind Faith album! Pull up a beanbag and pass me the bong!

TW: (Laughs) The birth of the Sony Walkman at the end of the 1970s changed all that and turned music into a selfish thing. I think that’s a little sad.

NT: The future for popular music is not great, is it?

TW: No. It’ll be AI generated with John Lennon’s voice recreated. In fact AI is already doing that, putting artists together who were never in the same room. Of course there are some positives. Ahmet Zappa did a tour of his father Frank’s music with a hologram of dad playing beside him.

NT: Do you think our generation will be the last one that wants to go down the road and listen to the SandFlys?

TW: (Laughs) Oh, there’ll always be a place for live music, but people have to get paid to play, and they should because it sells booze. But for that reason you end up with a live audience which isn’t listening, they just talk over the top of the music. That’s a little sad too.

Vinyl Dreams will be launched at Noosa Arts Theatre on Friday 9 June from 6pm, with virtuoso drummer Duncan McQueen demonstrating the rhythmic moods of ‘70s music. It is a free event but registration with Annie’s Books would be appreciated. 5448 2053 or info@anniesbooks.com.au