Global telecommunications had its humble beginnings in 1858 when two battleships met in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and connected the two ends of a 4000 kilometre cable, allowing Europe and North America to communicate via telegraph.

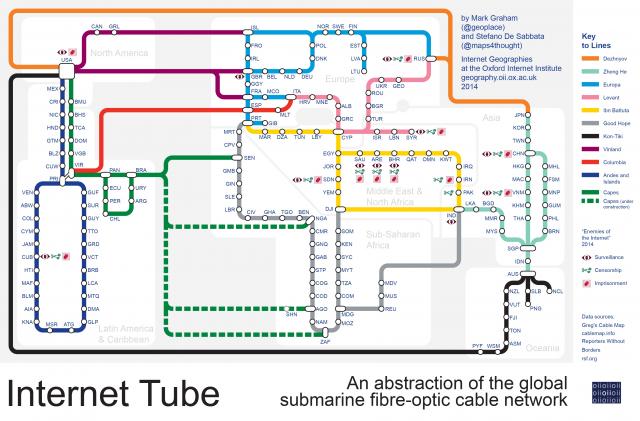

Since then, many hundreds of undersea cables have been laid, and continue to proliferate around the world, but it seems bizarre that such a seemingly antiquated delivery system, rather than satellites, or something invented last week, still serves as the backbone of the internet and the messaging systems used across the world.

And while traders have moved money around the known world since Roman times, now, just one high-volume user, the Belgian money mover SWIFT, facilitates more than 45 million financial messages and US$5 trillion in money transfers per day via the 1.3 million kilometre spaghetti network of undersea or submarine fibre optic cables.

Who knew that all of this was happening along the mountains and valleys of the world’s seabeds? Certainly not this writer, who laboured under the delusion that emails and Tweets mysteriously bounced around off satellites for a nanosecond or two before being delivered.

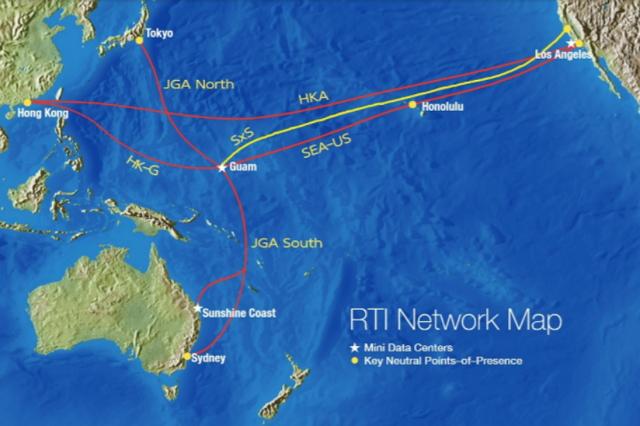

But two events last week made me realise the full extent of the undersea traffic and the complex management of it, made more pertinent to our region since the opening of the $35 million Sunshine Coast International Broadband Network cable and landing station and data centre in Maroochydore in September connected us directly to the world via a 550-kilometre branch cable from the main cable between Tokyo and Sydney.

The first was worldwide interest over recent weeks in the security of the submarine cable infrastructure in the face of suspected Russian sabotage of two gas pipelines in the Baltic Sea, and media speculation as to what impact similar acts might have on submarine telecommunications infrastructure.

The second was meeting a jovial Brit named Graham Evans, a marine geoscientist of some 44 years’ experience who, with his Indonesian-born wife, divides his time between a property at Doonan and an apartment in Singapore while travelling the world as one of the key figures in the $27.5 billion global submarine communications industry.

Since 1990 he has been regarded as one of the leading experts in cable route planning and survey, and is managing director of subsea cable business for EGS Survey Group, the multinational that helped develop the Sunshine Coast project up to building stage.

Graham also represents EGS on the executive of the International Cable Protection Committee, for which he is currently serving his second term as chair, and is one of the reasons why the

first face to face ICPC Executive Committee meeting since 2019 was held in Noosa last week. Graham makes no apologies for the fact that the executive strives to hold its meetings in exotic locales (the last one was in St Lucia), and if you happen to live in such a place, why not bring it home?

But if that makes the ICPC sound frivolous, it is anything but.

Attendees at the Noosa meeting included most of the 17 elected members of the committee, the ICPC Secretariat, International Law Advisor, United Nations representative and Marine Environmental Advisor, who over three long days thrashed out the issues of the day and received a presentation on the future of the local application from Sunshine Coast Mayor Mark Jamieson.

Founded in 1958, exactly a century after the first undersea communications cable was laid, the ICPC was originally quite a small club of academics and experts in seabed activities, but in 2010 in response to the growth of the industry, the rules were changed and the organisation opened up to companies involved in submarine cables.

Says Graham Evans: “Anyone actively involved in the subsea communications industry can now join ICPC, and we currently have 185 member companies and organisations, including the Australian Government, from 60 countries, representing 97 per cent of the world’s telecommunications cable ownership.”

When we met for coffee in Noosaville after the conclusion of the executive committee meetings, Graham was affable and understanding of the astounding depth of my ignorance of his industry (“Oh, I get that all the time”) and agreed to help me interpret my research.

But first we had to address the elephant on the Grind terrace, being the increasing media hysteria about the seabed becoming the next battlefield in a Cold War that is approaching lukewarm, fuelled for me by having read a long article on the Politico news site titled, Will Russia attack undersea internet cables next?

The article began: “Explosions at two major national gas pipelines connecting Russia to the European Union have Western policymakers asking: what will be targeted next? No one has yet to take responsibility for the attacks against the Nord Stream energy pipelines. But American and European officials have been quick to point the finger at the Kremlin – amid warnings the labyrinthine network of undersea cables that power the global internet could be an inviting target.

“So far, few, if any, of these internet cables – which connect all of the world’s continents and represent the digital superhighway for everything from YouTube videos to financial market transactions – have ever been sabotaged by foreign intelligence agencies or nongovernment actors. But the threat is real.”

It took Politico a couple of thousand words to conclude in the last paragraph that internet sabotage didn’t make any sense for anyone, but Graham Evans cut straight to the chase.

“Russia and China have the ability to attack specific cables, but it affects them as much as anyone, so it would be cutting off your nose to spite your face.

“And with the diversity and resilience we have today, it makes it a futile exercise.

“If you go back to the 19th century, when people started building infrastructure for communications, one of the first things countries did was try to destroy it. There’s a history of opposing countries trying to cut each other’s communications. In the early days it was telegraph cables carrying a few channels.

Now you can carry hundreds of thousands of voice calls per second on one cable. The industry has built up resilience and network diversity, so if you blow up one cable, it’s not really going to make any difference.”

Which is why ICPC puts a strong emphasis on protecting its seabed assets from other threats. Said Graham: “Our vision is for security, protection and reliability. If you analyse the industry, you’ll find that there are breakdowns all the time, but they don’t affect people because of our diversity. That’s the protection part. We believe that all submarine cables should be charted. Why would we want that when there are malicious threats being made?

“The answer is that any bad actor will be able to find where the cables are, charted or not, so what we want to do is provide greater cable awareness for other seabed users, such as the fishing, mining, dredging industries. The big one is the increasing level of seabed mining beyond national jurisdiction, on the high seas beyond territorial waters.”

Climate change and rising sea levels also pose a genuine threat to the industry, with several legacy landing stations in Europe built too close to the beach already in danger of inundation, but one perceived threat that both amuses and infuriates Graham is the idea that sharks attack the cables.

He tells an amusing story about being interviewed at Noosa Spit for the National Geographic program Drain The Oceans, when he refuted the shark myth, only to discover when the program aired that he was introduced over a shot of a huge shark swimming towards the camera.

“Sharks do bite our cables, but if you want to put it in context, 83 per cent of all cable breaks occur in shallow waters of less than 200 metres and are caused by shipping or anchoring.

“The rest happen in deeper water from a whole bunch of causes, including a very small number of shark bites.”

Graham also derives some amusement from the fact that if someone complains that the internet is having a slow day, he can provide the answer.

“My dentist did exactly that the other day and I shocked him by knowing the answer – that a cable had broken down and slowed the system. What happens if there is a breakdown is that the data packets are automatically switched to another route and sometimes that route will be slower because the latency [transmission delay] is greater.”

The Sunshine Coast project is not only the first municipally-funded cable and landing station in Australia, it is the first outside the three cable protection zones declared in 2007, two in Sydney and one in Perth, which receive the bulk of our internet communications for distribution around the country.

So what’s in it for us?

According to Sunshine Coast Council, “The project will be a great incentive in attracting new business and industry, particularly organisations with big data requirements. High-capacity data connectivity straight into the economic powerhouses in Asia will be a massive stimulus for the local and wider Queensland economies, creating jobs and encouraging investment well into the future.

“The cable will help to futureproof the Sunshine Coast telecommunications capacity and increase our smart city capability, ensuring access to important data networks.”

I asked Graham Evans to drill down and idiot-proof that for a home NBN user.

I expected him to groan but he took a long pull of coffee and leapt in with enthusiasm.

“There is a tremendous local advantage in having a regional landing centre, some of which I didn’t foresee.

“What is happening is that they are building a facility to back-haul the data to Brisbane from what we call the ‘point of presence’.

“What that means for Queensland is that if there are breakdowns on the main routes, Queensland won’t suffer.

“As of now, the Sunshine Coast can offer the world a five-millisecond transit advantage over Sydney in the delivery of a packet of data. That advantage will also be made available to local users.

“If you’re currently using NBN, your maximum download speed is probably 70MB per second and upload about 20MB, whereas in Singapore I have 1GB per second, so there’s a huge space for improvement.

“Financial institutions in particular could be attracted to the Sunshine Coast by that 5ms advantage.”