Back in the mists of time, when we were new to Noosa and trying to establish a publishing business which would reflect the aspirations and values of new Noosans while acknowledging and respecting what had come before, I derived a lot of inspiration from long and frequently hilarious lunches with the visionaries of our town, a small but vocal group of thinkers and doers which included the architects du jour, Gabriel Poole and John Mainwaring.

Gabriel has moved on to the big design studio in the sky, but Mainboat, as he is affectionately known for his lifelong love of sailing and boat-building, is still professionally active at 75, although he concedes that these days he leaves the heavy lifting to his long-time partner Garth Hollindale in what is now known as Hollindale Mainwaring Architecture. While Garth takes the lead at HMA, now based at North Lakes, Brisbane, but with projects all over South East Queensland and beyond, John provides vision and inspiration while dividing his time between residences on the Gold Coast, Brisbane and Noosa.

Mainwaring grew up on the Gold Coast, went to the Southport School and got his first taste of Noosa as a young surfer.

He recalls: “Whenever a crew of us would come up to surf we’d pull into the old fibro Summers shop on the corner at Coolum for supplies. It had that wonderful light fibro façade and I just loved that building. Out on the rocks near the shop was an epitaph for Grommet, a local surfer who’d died in a house fire. ‘Grommet lives’ painted on a rock wall. [Local artist] Blair McNamara did a lovely painting of the shop and built that epitaph into it. The painting was part of my art collection gifted to Sunshine Coast University.”

Most of us keep our cherished memories in computer files or a shoebox under the bed, but John is fortunate enough to have them scattered all over town. In 1996 he won the Robin Boyd prize for the Chapman House on Noosa Sound, a sentimental tribute to the lightweight “shack” architecture of the Summers general store. His French Quarter Resort on Hastings Street, designed the same year, was his homage to the arrival of “the Frenchies”, a group of chefs and hippies who arrived in the 1970s and “introduced kerbside eating and changed the way we thought about restaurants”.

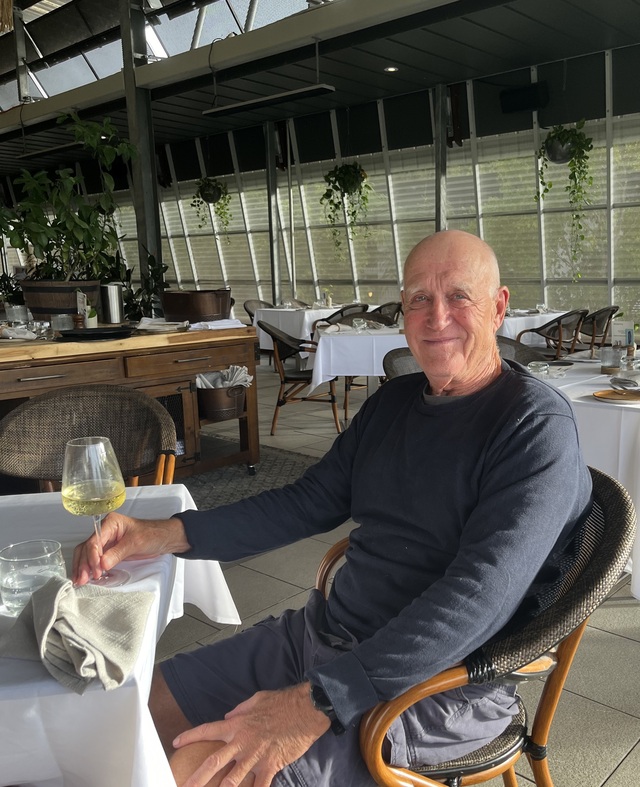

As he’s telling me all of this, Mainwaring, a mutual friend and I are sitting at lunch in the big, airy space of the restaurant at Peppers Resort, once known as View, which said it all, and is now called Park and Cove. Fittingly, this and the Viridian bush villas which adjoin are perhaps his and Hollindale’s grandest contribution to Noosa style. He says: “Every time I walk into Peppers I’m thrilled with the way the landscape fits in with the building and vice versa. That’s a great joy to me.”

The Peppers/Viridian project, on the deep valley and ridges behind Hastings Street that had once been the Freeman banana farm, later owned by the Hack family, was tossed around between developers before Mainwaring and Hollindale grabbed it. John recalls: “We created this place as a kind of village high street with fingers of construction working in with the contours of the valley. That was a huge undertaking but Garth and I did it ourselves and submitted it to the clients. They sacked the previous bloke who wanted to build a four-storey underground car park, and hired us. You just can’t build underground on sites like this, with huge metamorphic monsters of rocks underneath it.”

We’ll work our way back to Viridian soon, but first I wanted to take John back to his professional beginnings in Noosa: “I was sailing north on my racing sailboat in the late ‘70s, a time when there was a big migration from the Gold Coast, people who didn’t like the way the Goldie was going. Noosa was the utopia. I sailed into Mooloolaba and went into the yacht club one day and there’s Gabriel Poole sitting at the bar.

“He was a bit short on help so he asked me to work for him. We decided to open an office in Noosa because we knew it was about to happen. I sailed up there and bought land on Noosa Sound and designed a boatshed to put on it and build another boat. How naïve I was!

“But there were a lot of maddies on the river back then. These were the days of the barefoot architects in Noosa, and this place [Peppers] still imbues that with its light structure. During that era there were more Robin Boyds awarded on the Sunshine Coast than anywhere else in the country, because, together with Lindsay and Kerry Clare, we developed this distinctive laidback approach and response to shadow and light. Of course, Gabriel took it to the extreme with his tent houses.”

Mainwaring references Noosa’s barefoot architecture era regularly and fondly, but like most architectural movements, big and small, it had its roots in earlier times. In Noosa’s case it was the partnership of Brisbane architects Aubrey Job and Robert Froud, who set up shop in Hastings Street nearly two decades before Mainwaring and Poole, and started designing environmentally sympathetic homes for new arrivals, a few of which survive. But the barefoot architects of the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s painted on a much larger canvas, and serviced a far bigger client base.

By the ‘90s large scale developments like Noosa Sound and Noosa Waters were challenging the “keep it light and simple” paradigm, but typically, Mainwaring had a response that turned heads.

Winner of the 1993 Queensland house of the year award, John had accepted a commission as design consultant for Noosa Waters, and, as if to prove what could be done with imagination, he designed the award-winning Canal House 1, also known as the Wave House, for his young family. Having just launched our house and garden magazine, Casa, in tents on the vacant block next door [one of many at the time], we featured the “surrealistic discord” of this stunning and vividly-coloured waterfront on the cover of the second issue, published 30 years ago this month. Although the colour scheme has been toned down, perhaps in keeping with the blandness of the times, the Wave House still sits at the water’s edge behind a screen of greenery, surrounded by the block-filling mansions that are the bane of Mainwaring’s existence.

The defining statement on the website of Hollindale Mainwaring Architecture notes: “At HMA we deplore imported styles and artificial real estate values. Our basic attributes are in response to site, vista and climate. Spatial dynamics and function are primarily of more importance than form. Architecture consists of a series of spaces created by a composite of varying materials, surfaces, landscape, environment and view lines. These elements combine vertically and horizontally, adding a fourth dimension to the experience of the user.”

Over the second, or possibly the third bottle of wine at Peppers (see, I told you we’d get back there) Mainwaring takes it further: “I think it all began to change around the time of the global financial crisis when places like Noosa Waters started putting in these monstrous block fillers. It was a response to a change of demographic, and also to the new stuff, like the internet and, in architecture, the International Style, which was like an epidemic. One bloke on Noosa Waters had amalgamated three blocks to make this monster of a place which had the biggest retractable door ever built. I can’t really get my head around that, but life is full of contradictions.

“I have to say that where I live here in the first stage of Viridian, a little stilt house in the forest, I’m sick and tired of cleaning the mould off the ceilings and the floor. (Laughs) The irony is that we came to Noosa as part of the anti-high-rise movement and yet they hauled me back to Brisbane to design the centre of the city [Queens Street Mall]. That’s the story of my life. You have to come to terms with the contradictions.

“In the Noosa context, I think that what’s been done by the Parks Association and other groups to preserve the natural environment, plus the mostly sensible landscaping in the public space has helped to neutralise a lot of what I call the ‘Me-Me’ architecture which has become predominant, usually for people who have come to paradise but brought their own set of values with them.”

![[READER COMPETITION] – Win tickets to the Queensland Ballet at The J Theatre](https://noosatoday.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Queensland-Ballet-100x70.png)