Several years ago Cootharaba property owners Montserrat Martinez and John Charlton were wandering along the Gympie Terrace riverfront when they stumbled across a jazz combo being propelled by the mellifluous lead of someone who knew his way around a jazz guitar lick.

John, a longtime musician himself, remembers: “My first thought was, who is this guy? His playing was just remarkable.

“A few days later, we go to a council workshop on land care, and there’s the guitarist, talking to people about how to look after their properties. Since my partner Montserrat and I own a beautiful 37-acre place in the hinterland, we asked him to come and take a look at it and give us some advice. That was how we met Dave Burrows.”

The seeds of this friendship, that grew out of a mutual love of music and nature, had been sown, but this was years before Dave Burrows was to become Noosa Council’s conservation partnerships officer.

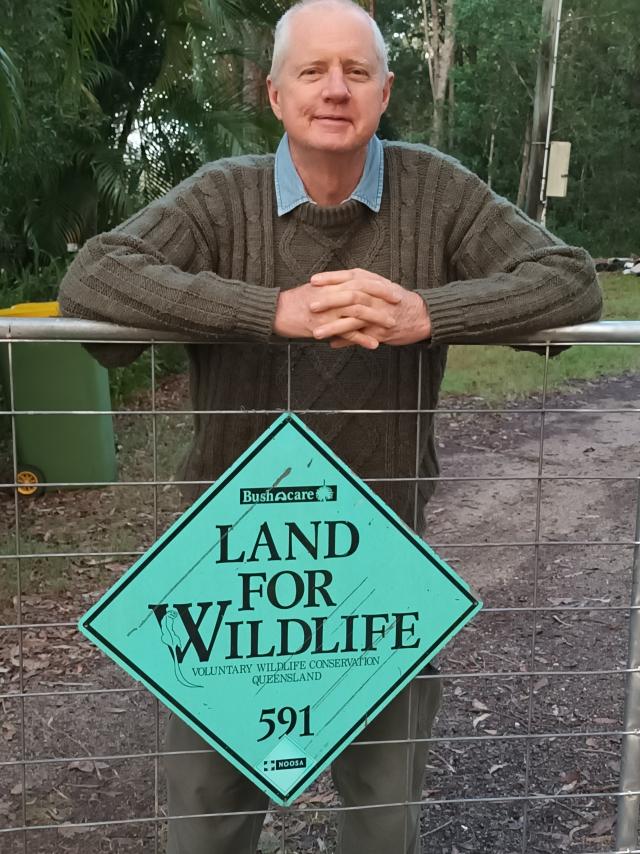

In fact Noosa had just been amalgamated and Dave was on the move to Sunshine Coast Council, but not before he’d signed up Montserrat, John and their beautiful Mas Montserrat for the Land for Wildlife program.

In his Pelican Street office a couple of weeks ago I asked Dave what came first – his love of music or love of nature?

“Music and the bush are equal passions for me,” he said.

“Nature and playing music are two of the best things in life. Not that I go out and strum my guitar under an old growth tree that often, but when I go camping up the river I’ll take an old battered guitar. I’m a luthier as well as a musician, a builder of stringed instruments.

“I’ve been doing that for 30 years and I love working with re-purposed wood. It’s a meticulous craft that takes a lot of time and concentration but for me it’s a meditation.

“And then there’s that exciting moment when you string it up and hit that first chord. I play my own instruments most of the time, but I also have some vintage guitars that I’ll pull out from time to time.”

Trolling through social media looking for Dave’s musical past, I found a photo of a much younger muso/tree hugger playing with an Irish folk band called the Famous Jimmies.

“That was a seriously long time ago,” he says.

“I used to play the Irish bouzouki as well as guitar with the Jimmies. I also played at the Jazz Party over many years, playing with many of the greats which taught me a lot. I played with Frank Johnson’s group at the Reef Hotel on Thursday nights for a while too.

“These days I work with a fantastic singer called Amanda Gilmour in a duo called Jazzstring. We get a couple of gigs a month, which is quite enough when you have a day job. I mainly focus on early jazz now, 1920s to 1950s.”

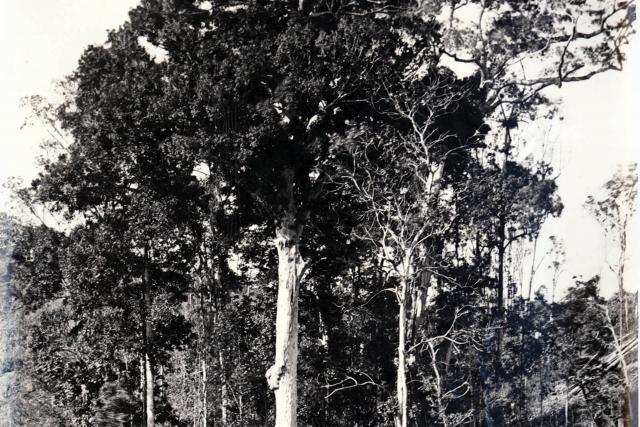

Says John Charlton: “The passion he has for both music and the bush is unbelievable. He’s got an amazing guitar workshop on his property at Cooran where he works meticulously, building these instruments he loves. “But you should see Dave when he sees a Southern Penda [tree], which only grows in a small triangle from Boreen Point to Cooroy to Kin Kin. His eyes light up and he just gets very happy. He knows this area so well, it’s amazing.

“A couple of days ago we were driving down the bottom of our property and he suddenly said, ‘Stop!’. We were looking at the trees we planted three and a half years ago which are now five to six metres tall, and he looked over and smiled and said, ‘We did that!'”

The hands-on work that makes Dave so happy is actually part of a multi-tiered environmental protection plan aimed at private property.

The bottom rung, if you will, is SEQ Land For Wildlife, a regional collaboration with a co-ordinator who manages it over all 13 local government areas in South East Queensland.

Says Dave: “There are a lot of similarities in wildlife across SEQ but Noosa does have quite a few species that you don’t find elsewhere. It’s a bit of a biodiversity hotspot. LfW is a voluntary program where council provides services to help sustain your property, a program that’s been going on across the region since 1998.

“The way it works is a landowner rings me up and I go out and do a site visit, then I do a property assessment that gives them an understanding of the values on their property in terms of native plant diversity, what native animals they can expect to be on the property, what the threats are from weeds, and so on.

“They get a sign to put up on their gate and a lot of written material, plus they get invitations to workshops and field days.

“There’s also an incentive program where they can get up to 380 trees a year and we can send out contractors for a day to teach them how to best manage weeds.

“It’s primarily an education program, particularly since Covid when there was a big migration from the southern cities, people coming up here for a tree change, which is great but a lot of them didn’t have a clue about how to manage land.

“I try to instill in them a sense of respect and custodianship for the land, rather than thinking they have to control or dominate it.

“Often they just need to be given some direction and behavioural change follows. I don’t mean in a didactic way, but in explaining what their options are in caring for their land.

“Having field days where they can meet other like-minded owners also really helps. It’s peer to peer learning.

“LfW is about rebuilding connectivity in the landscape and protecting some regional ecosystems that aren’t well protected in national parks.”

A Voluntary Conservation Agreement is higher level program in which owners put a voluntary protective mechanism over part of their land.

As Dave explains: “In many cases it will be that the owners have been in Land for Wildlife for years, they’re getting on a bit now and they know if they sell it’s a lottery as to whether the new owner will share the same values.

“By putting this protective mechanism in place they ensure protection over successive ownerships.

“It’s a big step for people to take because it puts a third party interest over your property which scares some people off, but at the end of the day it’s a matter of trust.

“A big part of my job is building trust, and that only comes from a long-term relationhip with the landowner. Because I represent council in that relationship, it often becomes a very personal thing. I become the bridge, or the enabler.

“The VCA process begins when an owner expresses interest and I come out with a big aerial photograph of the property and ask them where they want it. There’s a lot of explaining because I want them to think carefully about where the VCA covers.

“You don’t want it over your house or a big chunk of land around the house. “You want it over bushland on the property. I also advise them to get independent legal advice before they commit, but they rarely do.

“So we identify the area, then we do an agreement.

“If there’s a mortgage we have to ensure the lender agrees to it, and if they have more than 30 per cent equity they’ll probably say no.

“Once those hurdles are overcome I get a surveyor to do a survey plan of the area and we move towards signing off on the agreement.”

There are currently 23 VCAs in Noosa Shire, all under Dave’s guidance, and as he nudges closer to retirement he is acutely aware of the need for continuity in the relationships he has developed.

He says: “There is a succession plan. I’ll be getting a helper soon – Sunshine Coast Council has seven of me, Noosa has only one – and I’ll train and mentor that person over the next three years or so and then start to make a graceful exit.

“Out of respect for the landowners, I want to make sure that our programs will continue to be well looked after.

“We can only survive and thrive on trust.”