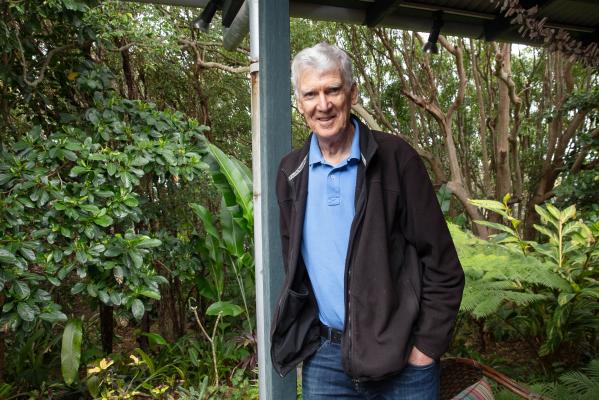

Our most esteemed playwright David Williamson and writer wife Kristin have called Noosa home now for a quarter century. The place they love so dearly has taken them from the peak of their careers to the contented golden years.

But while the doting grandpa may have mellowed from the enfant terrible who turned Australian theatre upside down with his depictions of real Australians in such plays as The Removalists and Don’s Party, he still has the fire in his belly, as he demonstrates in his fascinating memoir, Home Truths, being launched in Noosa next Friday.

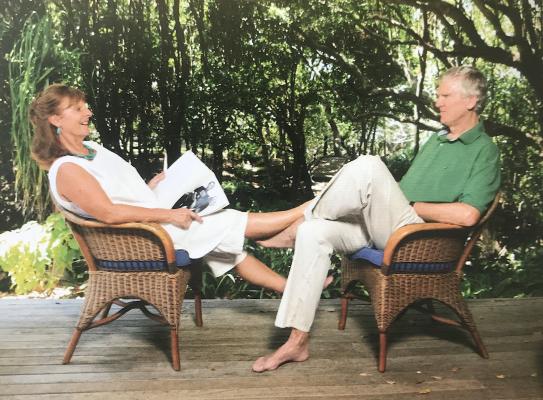

While David does not hold back in describing the friends and foes who have peopled his storied career, he also reflects with honesty and compassion on family, marriage, and on the couple’s abiding love of Noosa. I sat down with David for a long and entertaining conversation at their charming beach home. – PHIL JARRATT

PAGE 133

“It wouldn’t be until a few plays later that the ambitious playwright in me accepted that if I was drawing from life I had to be a little more aware of the possible damage I was doing and to give everyone involved the chance to read my drafts before the play was finished.”

PJ: Did you actually do that?

DW: Yes. I came to the position that if any of my fictional characters could be seen by any real characters as versions of themselves, it was only right that they should read the draft before it became final. Most were fine, some had objections which I addressed, but by and large it was recognised that it really was fiction, although you might use certain characteristics from real examples, including your own. I never felt that I’d put a real person on the stage, but nevertheless, some people did find it a little close to the bone in the early days.

PJ: Including Kristin, your wife.

DW: Kristin is such a smart, dynamic character that it was inevitable that parts of her would form the backbone of some of my best female characters. But she did get fed up when [actor] Robyn Nevin came up to her and said, ‘Looks like I’m playing you again!’

PJ: It must have been hard to hold back when you came to own the art of fictionalising the way real people behave.

DW: In the early days when I was starting out as one of the Carlton dramatists, the national theatre critic Katherine Brisbane came down and saw one of my short plays performed, and she said it was the first Australian play that she’d seen with real characters. I knew that was true because I always referenced life. I never felt easy about just making things up. I wanted what I wrote to be authentic. Most writers borrow heavily from life, even if they don’t admit it.

PJ: There are plenty of novelists who’ve done quite well by fictionalising their own life story over and over again. Did you ever feel a bit like that?

DW: The social dance we all play is what I was interested in. We’re all self-interested to some large extent, but we don’t want to push our self-interest too much on other people, and also, unless we’re psychopaths, we don’t like harming people. That’s the intricate dance. That’s what has always fascinated me and it’s what I’ve tried to portray on stage. But of course, the situations surrounding that change all the time, so you repeat the fundamentals of human behavior but the story changes.

PJ: One of the things that struck me in the book was that when you quote dialogue from plays you wrote as far back as 50 years ago, it doesn’t sound dated. Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll doesn’t pass the same test.

DW: I don’t think language patterns change all that fast in normal middle class society. When you’re working in a heavy working class vernacular, as Ray Lawler was, that will date. And human nature doesn’t change. In the Me Too age we males may tell each other that we’re enlightened, but underneath I don’t think the impulses have changed very much.

PJ: Let’s get you to Noosa for the first time, which in 1975 you described as “a relatively undiscovered little village”.

PAGE 168

“Having done my usual slapdash research I’d assured Kristin that accommodation would be easy to find once we got there. In fact, the place had only one hotel and that was booked out … We had hamburgers for dinner and Kristin told our waitress we were facing the prospect of sleeping in the car. The waitress said her boyfriend was a surfer who was off down the coast chasing waves and we could use his caravan. This was fine until midnight, when he returned to find his caravan occupied. We somehow squeezed him in and Kristin cooked him breakfast to thank him.”

DW: He came home and bashed on the door in a bit of a state, but he was genial once he found out what had happened. In those days Noosa was very much a surfers’ Mecca and it attracted a sizeable surfing community, as you well know.

PJ: The surfer you describe rings true to me. When I came north on surfing trips in those days I met a lot of odd characters, and most of them had a good heart, like this bloke. Do people like him still exist in our town?

DW: Well, my observation is that it has changed. When there’s a swell on these days you tend to see mostly former advertising executives with pony tails jogging along the coast track with their surfboards. (Laughs)

PAGE 170

“For subject matter I found myself continuously scanning the social environment around me for stories or situations or personal experiences that amused me, angered me or exasperated me.”

PJ: Did you find rich subject matter on that first trip to Noosa?

DW: No, not that time, although the kindness of strangers was something that stayed with me and I later used in my work. But Noosa hadn’t yet become what some of my more cynical friends describe as “South Yarra By The Sea”. It wasn’t chic. Barry’s On The Beach was the height of sophistication and its trademark dish was coconut prawns. (Laughs)

PAGE 280

“… Kristin and I decided to have a short holiday in Noosa … for our wedding anniversary. We stayed in a lovely beachfront apartment. Kristin’s diary notes that we had dinner on our balcony and watched entranced as glassy emerald breakers rolled with ruler-straight precision into Laguna Bay as the sun set behind them. This was paradise. Next night we had dinner at Palmer’s on Hastings Street. This was the first time we met the restaurateurs, Leonie Palmer and Stef Fisher … and a friendship started between the four of us that has lasted to this day.”

PJ: A lot of people probably have the idea that you got fed up with the big smoke one day and moved to Noosa, but as Home Truths illustrates, it was a long, suck-it-and-see process that involved other places beyond the cities.

DW: Yes, that’s right, going back to Hurstbridge outside Melbourne, where we lived with our “Brady Bunch” when they were small. Our holiday house at Pearl Beach [north of Sydney] was what convinced us you could build a community in a smaller place, but every time Kris and I flew up here and drove north along the coast from the airport, we fell in love with the sun, the surf and the natural bush that went for mile after mile. We just felt it was such a beautiful place. For me the defining moment when I knew our future had to be in Noosa was sitting at the front of Sails Restaurant when it was very new, having lunch on a perfect day with glassy waves rolling in, and looking at each other and thinking, well, we’ve been all over the world and there’s no place that can match this feeling.

PAGE 300

“I wanted out of Glitter City. And my sights were now set on the town where we’d just taken a holiday, Noosa. It had become much bigger, more consciously chic and more commercial than the pretty little fishing village we had first visited in the ‘70s … Visions of the beauty and tranquility of Noosa were now haunting me on a daily basis … It became an obsession. I had to get there and live the dream … [Kristin] agreed to let me buy a modest apartment at Marcus Beach …”

DW: It was 1996 and I was just sick of cities, and Sydney in particular. It can be a particularly bitchy city.

PJ: Unlike Melbourne?

DW: Well, that can be even worse! (Laughs) But as I wrote in Emerald City, no one in Sydney wastes time thinking about the meaning of life, it’s all about getting yourself a water frontage! I suppose at the time I felt out of kilter with the artistic mafia that ruled theatre in Sydney. They seemed to think that real life was dreary while I found it fascinating and, fortunately, the audiences agreed.

Anyway, I came up and Kristin followed. She was thriving in Sydney and thought I’d gone a bit crazy. The imprint of Noosa in the ‘70s was still so strong, that I thought, well, I’m a writer so there’s no reason I have to endure the congestion and the noise and the traffic and the personal aggro of a big city when I could live here and watch the waves come in, walk down the street and say hello to people, and write to my heart’s content. It was a sense of community as much as anything, because the big cities had lost that. It had become fragmented. We already knew that smaller communities worked for us because of Pearl Beach. Now I was thinking, why not do that all the time as a lifestyle? Surveys have shown that the happiest people live in Noosa-sized communities.

PJ: That’s become even more so since Covid.

DW: Yes, but there’s also a turnover of people because they come here looking for a physical paradise that will make them happy. After a while they find that they’re at an age where it’s not so easy to make new friends and all the old ones live elsewhere, so they sell up and go back where they came from. Friendships turn out to be more important than the view out the window. We found very early that the way to avoid that was to get involved in the community.

In Part 2 next week, David Williamson describes how living in Noosa increased his productivity and local characters provided new inspiration.