The weather had improved for my second day exploring the fringes of the Cooloola Wilderness, so I left the rooms at The Apollonian early, pedalled down to the Coffee Tribe for a brew and a bacon and egg muffin with the locals before the short ride up to the Habitat at Elanda Point.

The weather looked like holding so I locked the e-bike to a railing in the car park and set out on a long day’s hike, taking in the Kinaba Visitor Information Centre and the historic remains of Mill Point, Noosa’s first timber port and sawmill.

I have to confess that after living in Noosa for 33 years and exploring its far reaches often by foot and bike, I’d never been to Kinaba, although I did know a little of its history.

Throughout the 1960s, the pioneer members of the Noosa Parks Association and the Cooloola Committee had been engaged in a bitter fight to prevent sand mining in Cooloola, a campaign which eventually managed to shift public opinion and force the state government of the day to declare the area a national park.

Sir Thomas Hiley, who in addition to being treasurer of Queensland from 1957 to 1965, was a part-time Noosa resident and founder and president of the Bird and Wildfowl Association of Queensland (some suggested that the association was more interested in shooting wild birds than observing them) in 1970 offered the government financial assistance for “a project to promote the preservation and public observation of native bird species in natural environments”.

With the declaration of Cooloola as a national park, the opportunity presented itself for the government to save face over its previous policies to mine the area by building the Sir Thomas Hiley Information Centre as a gateway to the protected Upper Noosa River.

With $70,000 from the Bird and Wildfowl Association, a $50,000 grant from Treasury and a further $180,000 from the government, the project began in May 1978 and was completed ahead of schedule in September. T

he more than 30 workers on the project first built a barge to ship materials across Lake Cootharaba, then 168 piles were sunk for building and walkways. Spotted gum was used for the frame, steps and seating with cypress tongue and groove used for cladding, all unpainted.

According to Kinaba.org’s history page, Kinaba opened in March 1979 “amid much self-congratulation by Queensland National Party ministers on its building and the recent declaration of the Cooloola National Park”.

The walk into Kinaba (about six kilometres) through rainforest and paperbarks is an absolute delight, but it is surpassed by the walkways over the delicate wetlands at the edge of the river and the interpretive centre, all of this maintained by Parks and Wildlife rangers with the help of frequent working bees organised by the Friends of Kinaba – a great partnership between community and government.

The walk out from Kinaba seemed a little longer, perhaps because the sun had finally broken through, but when I finally reached the junction with the Mill Point loop track, I sat down under a shady tree, fortified myself with a water bottle and sandwich pulled from my pack, and was ready to tackle the last five kilometres on foot for the day.

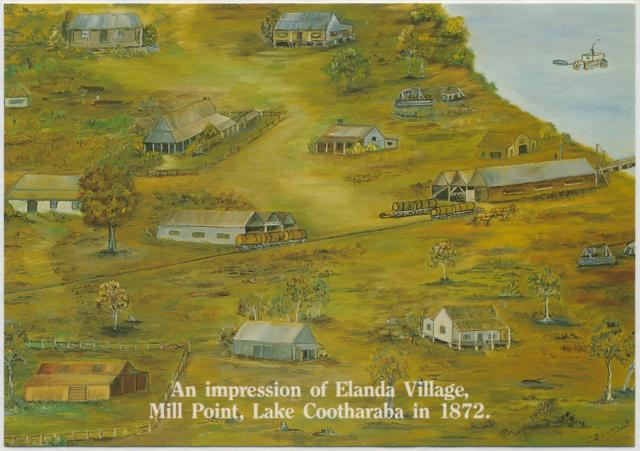

I visited what remains of Mill Point several times during the course of researching my history of Noosa, Place of Shadows, and it never fails to give me goose bumps, just to understand in small ways what life must have been like 150 years ago when timber-getters moved with their families to this remote and dangerous place. As I wrote in the book:

“In the late 1860s, some of the smartest business brains in the colony were to be found at the Gympie gold rush, and not many of them were fossicking. The majority who truly ‘struck it rich’ did so by providing goods and services for the fast-growing bands of dreamers. “Among them was an entrepreneur named Charles Samuel Russell, who arrived on the goldfields after having explored the timber potential of the Noosa lake country. He struck up a relationship with four men to whom the goldfields had already been kind, by virtue of the successful Caledonia claim, and who had quickly parlayed the profits into diverse business interests around Gympie.

“Over ales at one of the many rustic bars that lined the main street of “Nashville” (after James Nash, the man whose strike had started the rush in 1867), Russell told his new friends — Abraham Luya, James McGhie, Frederick Goodchap and John Woodburn — about the potentially huge profits to be realised from supplying the goldmines with timber. The five men agreed to become partners, and in March 1869, they applied for a timber licence and pastoral lease over the Lake Cootharaba land that had originally been Walter Hay’s. The plan was to develop the property as a farm while extracting as much timber as possible to send to Gympie.

By early 1870, the partnership had invested more than £2,000 to build an extensive sawmill at Mill Point, just to the north of Elanda Point … with a timber-getters settlement growing up quickly around it. As timber was sawn and towed on pontoons downriver, where it was transferred to paddle-steamers for the treacherous trip across the bar, and then on to Brisbane or Maryborough, the first real township in what would become Noosa Shire began to take shape on a bend of the river a few kilometres downstream. Mill Point’s growth spurt was therefore destined to be short-lived.”

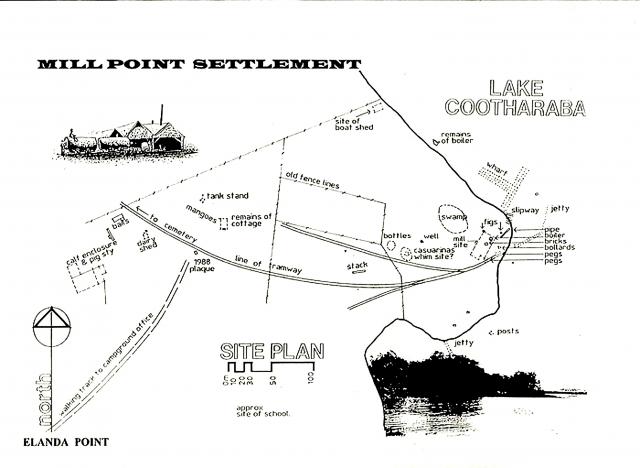

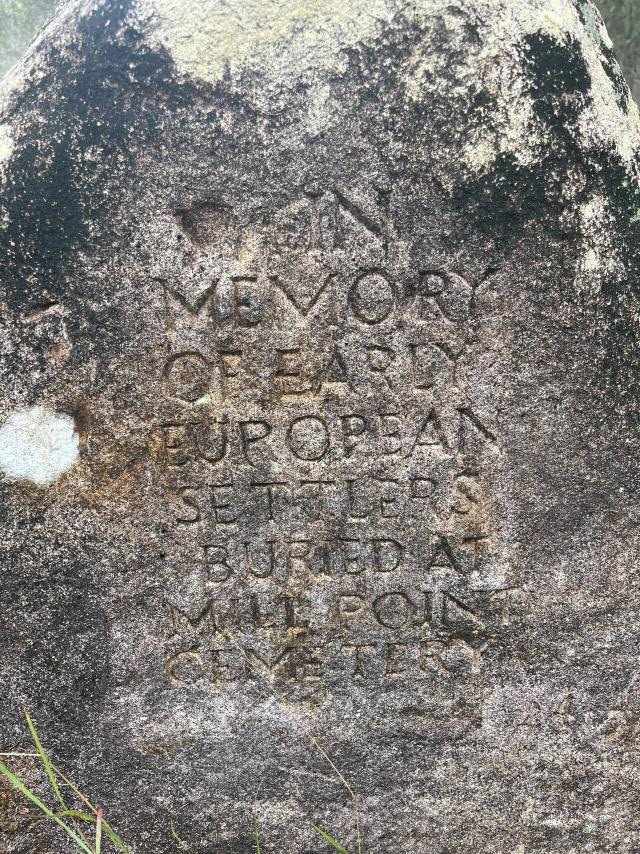

The growth of Tewantin as a river port did eventually kill Mill Point, but it took a few decades and a lot of pain and suffering for the small population who lived largely without support on the edge of the wilderness. A rock at the edge of the old cemetery carries the poignant message: “In memory of early European settlers buried at Mill Point Cemetery.” Many of the deaths were of the young children of the more than 150 workers – mostly preventable deaths if basic medical facilities had been closer – but the settlement’s biggest disaster was in July 1873 when a boiler in the sawmill blew up, claiming five lives.

Today Mill Point is a peaceful place, on weekdays mostly empty, but when you look carefully beyond the natural beauty, the reminders of tougher times are still there. Part of an old boiler that apparently didn’t blow up, a stone step leading to a workman’s cottage long since disappeared, and of course, all those unmarked graves beyond the stone.

I’d walked more than 17 kilometres when I retrieved my e-bike, so I decided to revive my energy levels with a cold beer at Habitat’s tavern while I gave the bike enough charge to get me the last 27 km.

It worked. Home before dark.