Former Noosa and Sunshine Coast councillor Vivien Griffin (now chair of Zero Emissions Noosa) and Noosa Landcare manager Phil Moran (who finished just outside the cut in this year’s council elections) have both been environmental warriors for decades. Now they are trying to secure Noosa’s future in the face of climate change. They sat with Phil Jarratt under the old growth trees at Landcare’s Futures Centre in Pomona for this discussion.

Tell me how you got here?

Vivien: When I started coming to Noosa I was working with the Nurses Union in Brisbane in the early 1980s, having gone back to university as a mature age student, and decided I wanted to work with the working class. I went to uni late because I’d come from a standard working class family where the girls didn’t do that. In fact, Mum got me a job when I was 14, as secretary to the deputy director-general of health and medical services. How that happened is a wonder of the public service! My parents were probably on the conservative side, but you didn’t talk politics at home, so I was politically naïve until I finally went to uni, where I did a quite useless humanities degree, but then did a post-graduate qualification in industrial relations because I’d decided that was the field I wanted to work in. The Nurses Union was emerging as a reformist group at the time. I started coming to Noosa in about 1981, and in 1985 I bought the block of land that I still have at Marcus Beach, and built a house on it in 1989.

Phil: I grew up in Brisbane and started work very early at the Breakfast Creek Hotel and the Tangalooma resort while still at school. My mother wanted me to be a lawyer, my father just wanted me to make money in business. The biggest hotel at the time was the Crest International so I started there as a trainee manager and after about seven years became their youngest ever catering manager. Then I quit and went to Indonesia with a friend, and that was when my education really started, when my social conscience was born, just through seeing how under-privileged these people were and how hard they worked. My friend was always interested in the bush and the environment while I was more in my father’s mould and I wasn’t. We travelled through Indonesia together from national park to national park for months, and by the end I just loved it. When I came back to Brisbane I didn’t want to go back into big hotels so I started my own business.

It seems odd that you grew up in Queensland yet it took a trip to one of the world’s most populous countries to awaken an interest in the natural world.

Phil: It’s a good point. I left Australia of 13 million people and went to Jakarta of 13 million people – quite an eye-opener. As a kid I was heavily into sports, but I didn’t really do much on my own. I went to Noosa a bit when it was just fibro sheds and caravans at The Spit, but mainly any environmental connection I had came through my friend who lived on 17 acres at Brookfield, where I started to notice the bush. I see a parallel with now, when so many young people put their earphones on and don’t have a connection with nature, and it’s very hard to educate them about the environment.

Okay, you were starting a business.

I borrowed a lot of money and bought a gourmet takeaway food and catering business called. Interest rates were over 18 percent and there were Energex strikes with blackouts all the time, I had about seven staff to pay, and my hair went white like yours! I developed a private catering arm and ended up getting into the legal market, doing boardroom lunches and so on for institutions like the Queensland Law Society, Barclays, Lloyds of London.

This was an extremely stressful time for me, but my late sister and her husband had a property near Mullumbimby and I’d go down there on my days off and help kill weeds on the block. I just loved it, so when I had to sell the business in 1990 because of arthritic issues, I bought acreage near Cooroy. By this time I was married with a little son, Harry, but we got divorced and I ended up buying a shed on 33 acres in Cooran with no power and a $75,000 debt. But I’d have Harry most weekends and he just loved it. No power so no TV or computer games, he’d bring his mates with him and we’d play forts or swim in the dam with the dog. And then I got together with the best woman in the world.

You’d made a tree change, exchanging a stressful city existence for a rural idyll, did it come with a new outlook on life?

Phil: Yes, I took up tree-hugging. I started volunteering for Noosa and District Landcare, doing potting or whatever they wanted done. It was a fledgling group with just two part-time employees and a tiny nursery. I was also setting up a wholesale nursery to supply native plants, which had become fashionable.

Vivien, take me through your early years as a Noosa resident.

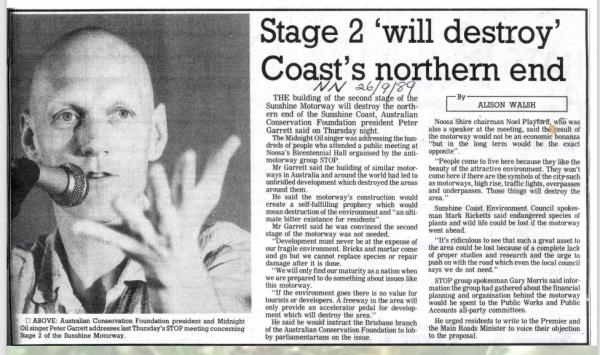

Vivien: I built this shell of a house at Marcus Beach. I would come up at weekends and it was soul balm to me. I’d sit on the deck at night and look at the stars and hear the ocean. It was what I needed. And then I got involved in Greening Noosa. The late Heather Melrose had a tree-planting group that would go up and down the coast once a month, and at the time the big environmental issue was where the next stage of the Sunshine Coast Motorway would go. Heather was strongly involved in that. The proposal was for the motorway to go straight up the guts of what is now Noosa National Park on the eastern side of Lake Weyba. There was a group called STOP (Save Today Our Parklands), which was predominantly Marcus Beach and Peregian people, but Peter Garrett and other prominent people got involved because it would have totally destroyed that magnificent corridor, not to mention the disaster it would have caused by dumping traffic into Noosa Junction. Fortunately, Mayor Noel Playford came up with an alternative proposal to put the motorway further inland, which was passed.

My first serious engagement in the environmental movement was quite by accident when a group of the Greening Noosa people were sitting around a picnic table discussing a submission to the public consultation process over council’s development control plan for the Marcus High Dunes, and I said I’d help with the typing. But it was going to be compromise, and I said, why would you compromise? So, I started not just typing but writing the press releases. I’d go back to Brisbane and send them out on the Nurses Union telex or fax.

Did you come up with “High Noon For The High Dunes”?

Vivien: I did, and it was my one marketing success. (Laughs) I’m very proud of it. I got myself elected to Noosa Council in 1994 when the High Dunes issue was being decided, and met one of the unsung heroes in that, planning director Raul Weychardt, who wrote a development control plan that created history by proposing no development.

Phil, did you become politically active in the green movement when all this was happening?

Phil: No, I didn’t. I was selling my plants, doing some landscaping and volunteering at Landcare. Then a job became available at Landcare as a project officer and I became a full-time employee, and have been for 23 years. But back then I had no political affiliations. I was an apprentice tree-hugger, I probably wasn’t even aware of most of it. My political activism took a while to develop. But through my work I knew Heather Melrose well – a wonderful, strong, savvy woman – and Raul Weychardt, who taught me so much without teaching me anything. People like that created a kernel within me, and I started to become more aware of environmental issues. But even now, at Noosa Landcare we try to be apolitical.

You’ve both mentioned Heather Melrose as a mentor. Vivien, can you tell us about working with her on council?

Vivien: What a remarkable individual! She’d do her homework so thoroughly. Some people claim the macro approach and say, oh, I’m not good at detail. Heather covered both. When we were fighting the Marcus Dunes battle, we got access to the T.M. Burke files and Heather had a list of documents that she wanted to see. But separating them was too hard so they just brought out all the files and dumped them on a table. We were like kids in a lolly shop! (Laughs) Another time they wanted to plant Mexican palms in front of Halse Lodge, an she fought that as hard as she fought for the Marcus High Dunes. Nothing got past her.

Why didn’t she run for mayor after Playford?

Vivien: Well, she retired and I ran, and wasn’t that a disaster! (Laughs) But fortunately Heather came back at the next election and served as councillor again.

Not to dwell on a disaster, but what made you run for mayor against Bob Abbot?

Vivien: It was a dumb decision, but Noel was stepping down and I wanted to see his legacy continue, and I also realised that if Bob got in, there would be no chance of beating him next time. There was no chance of beating him then, but I hadn’t realised that.

Phil, explain your political awakening.

Phil: I started to realise that it wasn’t the dark side, it was the green side. I learnt so much from my property. I always describe my 33 acres as a university without the sandstone. I’d find a butterfly and go back to my books and learn all about it, and I’d teach my son Harry about butterflies. We’d catch fish in the creek and put them in the aquarium until we’d identified them, then let them go. I probably first put my toe in the political water under CEO Bruce Davidson, who was a great operator. We’ve mentioned mentors, and I’d add Paul Summers for his work on establishing the population cap, and the mayors, Playford, Abbot and Wellington, although I may not have always agreed with them.

What do you think our environmental future would look like if we hadn’t de-amalgamated?

Vivien: It’s very hard to say because the direction of a council is shaped by its councillors, and the amalgamated Sunshine Coast Council that came in 2008 had Bob Abbot as mayor and he was a respected, unifying force, and we had the numbers to get good things done for Noosa. At the same time, there were some very silly decisions, and I wouldn’t be optimistic about what might have happened if we’d remained amalgamated.

Phil: I’d never marched in my life but I was at the Brisbane protest march against amalgamation with my wife Kim. I thought it was a terrible decision. But there were good people within the Sunshine Coast Council and there was more money in the environment levy, so when de-amalgamation started, I was in two minds, but what swung me was the fact that there is something special about Noosa. The Biosphere was happening at the same time and I was on the international recognition working group, so that increased my feeling that Noosa had to be independent. The Biosphere board came up with a slogan, “keep Noosa special”, which was bagged for being elitist. But Noosa is special, and nothing has proven that more than how we’ve handled Covid.

Vivien: But Noosa has to get out of its comfort zone, and the first step is to recognize that you’re in one. Years ago my mum had a Davis Gelatine cookbook in which every dish was made in aspic. Noosa is a bit like that – it’s in danger of being locked in aspic, complacent about its past achievements, but not looking over the parapet at the really serious challenges that face not only us but the whole planet. Our small community could be a world leader in climate change action. To me, that’s the only game in town.

I agree there’s only one issue, but climate change is multi-faceted, and the roles you two play are evidence of that.

Vivien: It’s economic, it’s social, it’s the environment. It affects every business in town. Most importantly, it’s about what we leave behind. Every grandparent in Noosa should be rising up to help us win this battle for future generations! And economic and environmental benefit has never come together as well as it is now. Right here at Landcare, these guys are about to put 9.4 kilowatts of power on their roof.

Phil: And that’s not so much a tree-hugging decision as an economic one. The writing is on the wall everywhere. I’ve had the view for a long time that the economy and the environment are not incompatible.