One year after the Second World War a group of Victorians banded together to seek the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne. The Victorian Olympic Council (VOC) had reserves of just (pound symbol) ;6 7s 1Od (that is, less than $13) when it reconvened in June 1946, the first meeting in seven years. It is not surprising then that there was much laughter when RonaId Aitken moved a motion for the VOC to apply for Melbourne to host an Olympic Games. However, the motion was accepted – unanimously.

Edgar Tanner, Secretary-Treasurer of the VOC, forwarded the proposal to the Australian Olympic Federation (AOF) the next month, and then asked the IOC how to proceed with the bid. Tanner gained support from the then Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Sir James Connelly, and Sir Frank Beaurepaire, a former Lord Mayor.

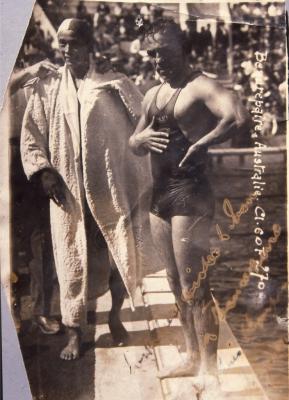

Beaurepaire’s public profile in Australia and in the International Olympic movement was a

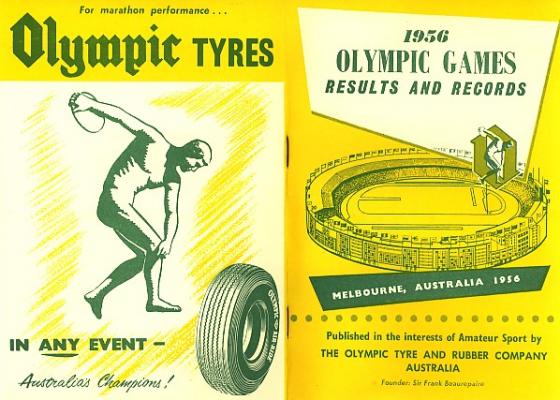

key factor in the success of Melbourne’s bid. He had won three silver and three bronze medals at Olympic Games (1908, 192O and 1924), and had been an official at the 1932 Olympics. Following his return from the LA Games, he developed his tyre business utilising the brand name ‘Olympic’.

When he assumed the presidency of the VOC in May 1947, Beaurepaire was instrumental in urging the Melbourne City Council to establish an Invitation Committee comprising influential media and businessmen.

Lord Mayor Connelly announced an application would be made to the IOC in May 1947

to host the XVI Olympiad and, in January 1948, an invitation was sent to the IOC for consideration at its meeting in St Moritz in Switzerland. Copies of an extravagant ‘Invitation Book’, with additional copies bound in either suede or merino lamb’s wool, were sent to all IOC members, international sports administrators and public figures. The book outlined reasons why Melbourne should become an Olympic Games host:

Australia was only one of four nations to attend every summer Olympics and consequently it was the senior Olympic country in the southern hemisphere;

if the Olympics were truly ‘world’ games, it was time for them to be held in the

southern hemisphere;

and, with the development of pressurised aircraft, the thirty hours travel to Melbourne was comparable with other venues.

The Invitation Book also claimed that Melbourne’s bid had the “active interests of all athletic organisations, government and the people”. To counter the criticism that athletes in the northern hemisphere would be competing ‘out of season’, it was suggested that this was normal situation for southern hemisphere athletes.

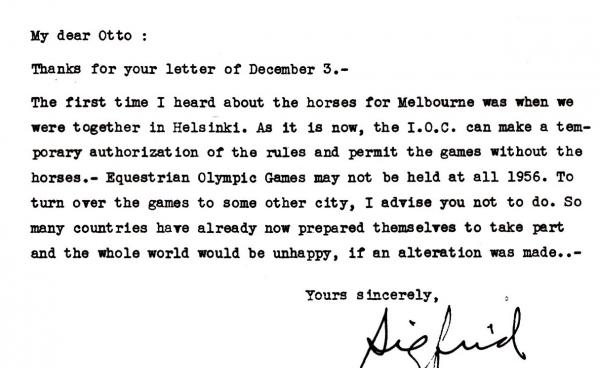

President of the IOC, Sigfrid Edstrom, commented he had been impressed by the vigour and capacity of Australians when he visited there, stating he would meet with the Melbourne Invitation Committee during the 1948 Olympic Games in London.

Beaurepaire was quoted in the Melbourne Argus of October 28, 1948 stating the ‘betting odds’ as “Melbourne – even money; Buenos Aires 6/4 against; Detroit 2/l; All others Buckley’s chance.”

There was also speculation at this time that, if Melbourne did not get the Games in 1956, it was certain to get them in 1960, “provided it kept up the propaganda work”.

Frank Beaurepaire’s efforts were extraordinary. For example, he organised the delivery of Australian food and wine to the London Lord Mayor’s Banquet in 1948, which in ration-ridden England was much appreciated. However, gift-giving to IOC members has a long history but in one instance it almost backfired.

A case of Australian wine sent by Beaurepaire to Chicago as a gift to the newly-elected President of the IOC, Avery Brundage to be delivered to his personal residence. This was a ploy which led to a protracted period of correspondence between Brundage and the Illinois Liquor Board. From the amount correspondence located in the ‘Brundage Collection’ of personal papers, about this ‘gift’, it was clearly not a positive endeavour.

Although it was expected the IOC would decide which city would host the 1956 Olympic Games at the London Olympics of 1948, the decision was postponed until the IOC members met the following year in Rome. Australians lobbied extensively during the 1948 Olympic Games, with Beaurepaire and Connelly actively promoting Melbourne’s case in London and Europe for almost three months.

Beaurepaire and the other members of the Melbourne delegation were the last to present their city’s case to the IOC in Rome in April 1949. Six United States cities were bidding, with Detroit and Los Angeles the main contenders. Other bidding cities were Buenos Aires, Mexico City and London.

Forty-one IOC members voted in the fourth round; Melbourne won narrowly – 21 votes to 20 secured by Buenos Aires.

‘Melbourne Gets the Games’ was front page news in the Victorian press when it was announced on 30 April 1949. This should have completed the story of the Melbourne bid, but it didn’t because Melbourne subsequently came close to losing the Games.

The strategy of the Melbourne Invitation Committee before ‘decision day’ had been to proceed with anything likely to persuade the IOC to award the Games to Melbourne.27

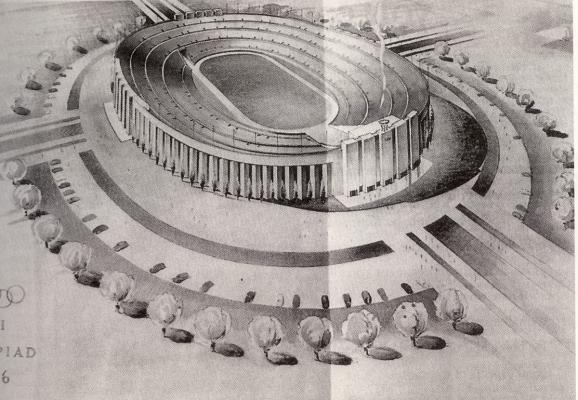

The extravagant plans for a new Olympic Stadium and Swimming Pool complex were two examples. The Olympic Organising Committee vacillated over the site for the main stadium – Olympic Park, Princes Park, the Royal Agricultural Society Showgrounds and the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) were all mooted. Avery Brundage expressed deep concern over the lack of progress.

On the day Brundage visited the MCG (the Olympic Stadium) in April 1955, “there were only five workers on site trying to do the work of 100 men” because of an industrial dispute. At the end of his tour, Brundage was quoted as stating “I can tell you that more

than ever the world thinks that a mistake has been made.”

Brundage lamented that in the six years since Melbourne had been awarded the Games at Rome in 1949 there had been “nothing but squabbling, changes of management and bickering’. He regarded Melbourne’s record in its preparations for the Games as deplorable – “a matter of promises and promises.”

Brundage intimated that even less than eighteen months from the Opening Ceremony designated for November 22, 1956, several other cities (he seemed to favour Philadelphia) would be prepared to stage the 1956 Games.

Avery Brundage’s scathing criticism seemed to work; it galvanised action and greater co-operative effort among the individuals, committees and agencies.

Another problem which surfaced for the 1956 Olympics was the revelation that Australia’s strict quarantine laws would prevent equestrian events being staged in Melbourne. They were held instead at Stockholm – the first time Olympic events were held in more than one country. The quarantine continued to be an issue for future bids by Australian cities.

Despite the difficulties and controversies, the Games of the XVI Olympiad were staged most successfully and have been heralded as ‘the friendly Games’ ever since.

The proposals for Olympic Games in 1972 and 1988 in two different cities will be considered in Noosa Today next week, along with a bid city closer to the Sunshine Coast following the success of the 1982 Brisbane Commonwealth Games.

(Ian Jobling is Honorary Director of the UQ Centre of Olympic Studies at The University of Queensland)