As the Voice referendum campaign winds up I’ve been trying to put a finger on which part of the No side’s farrago of misinformation, transmitted mostly on social media, has resonated with some people to such a degree that they have foregone research and reason in making an informed voting decision.

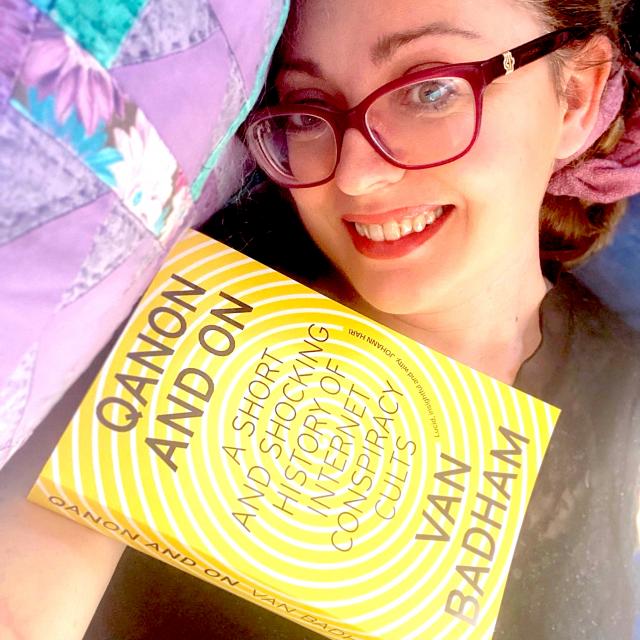

Following the long threads down the rabbit holes of fear-driven fantasy about three per cent of the population being authorised to determine flight paths and the purchase of nuclear weaponry, creating a “black veto”, not to mention taking back our houses by force, I was reminded of a transcript I’d made of a talk given a few months back at Noosa’s Floating Land festival by author Van Badham, a fearless feminist who had spent more than a year undercover investigating the dark underbelly of the internet while researching her book, QAnon and On: A Short and Shocking History of Internet Conspiracy Cults.

What Badham uncovered about the world of nutty neurotics involved with the US-based fear factory QAnon, and its frightening tentacles reaching into Australia, of course goes way beyond anything we have seen on social media during the Voice’s No campaign – a foundational plank of QAnon, for example, is the idea that American celebrities of liberal persuasion, like Hillary Clinton, Oprah Winfrey and Tom Hanks, are actually “reptoid” lizard-people who practice witchcraft and gain superpowers by drinking the blood of children at gatherings in underground pizza restaurants – but in reviewing my transcript and an excerpt from Badham’s book, I was struck by similarities in the social media recruitment methodology, where one disgruntled believer takes a shaky premise to even more outrageous unlikelihood in order to attract the attention of another outlier. And so it goes.

By no means all, or even the majority of the No supporter posts I saw on social media went far beyond the dodgy “10 Reasons To Say No” assertions distributed by the Nationals, but a significant minority were clearly building a false case within the comfort zone of an online cohort of fellow believers, which is the process of cult creation outlined by Badham, one that with alarming frequency can leap out of the internet and into the real world, which is what it did in Washington DC with the siege of the Capitol on 6 January 2021.

In her Floating Land address back in July, Badham spoke about her first encounters of internet hate-speak spilling over into her real life: “I did an episode of Q and A in 2016 and over 1000 people called me fat [on social media] in one hour. I had people stalk me and others set up a telescope to peer into my apartment, and finally I was bashed on Bourke St, Melbourne at 9.30 in the morning. A package of photos of gang rapes and genital mutilation was dumped at my door. I ended up in court six times to try to stop this from happening. I couldn’t understand how writing against the work-for-the-dole policy had brought this down on my head … but compared to some other advocates in Australia, I got off lightly. It’s been a very distressing time for a lot of normal, progressive people … It’s happening to Thomas Mayo from the Yes campaign right now.”

Badham’s subsequent research into cult craziness on the internet led her into investigating the spread of QAnon around the world, particularly since the start of the Trump presidency. She said: “The tipping point for me was when an old friend who had once been in a cult was having marital problems and she and her husband had gotten into yoga to see if that helped. The yoga teacher had flipped out and became a QAnon person, and when my friend explained that this was not a real thing, she was shunned by the yoga community, to the extent where if she walked into a café, anyone from yoga would walk straight out. She was heartbroken. I thought I had to write a book about it. When I talked to other friends who were practitioners of things like herbal medicine or in the general area of wellness, they told me it was everywhere.”

In 2020 events in America compelled her to write a newspaper article about QAnon. She recalled: “Early on in the pandemic a guy was exposed in the US as running one of the QAnon websites where you had to pay to link in and have your say, and it turned out he was a vice-president at Citibank and he had an interest in data-mining. It was the perfect scam because if you could convince people that Hillary Clinton eats children, you can convince them of anything. This guy had made millions out of this. I wrote a piece about it for The Guardian and [the response] literally exploded with thousands of messages from people saying their father, brother, friend, husband, whatever, had been sharing these crazy stories and believed them.”

But what state of mind would you have to be in to become a believer?

Badham: “The pandemic was a time when people either coped or they didn’t, particularly in Victoria. For a segment of the population it was terrifying because they felt a lack of control, and the way they responded was to go on the internet chat rooms and be told that the lizard people were behind it, or that Big Pharma had put the virus into homes via sprinkler systems. Totally mad stuff. It’s called the paranoid schizoid position and it can happen to anyone in certain situations, which is why it’s really frightening. If you’re under pressure and you’re being overloaded with information, the brain can split, as they call it. If there’s too much nuance to deal with, it goes into black and white – bad people who eat children and good, brave people who go on the internet and talk about it. Part of that process is to blame minorities. We know how the profile of a bigot works. If something goes wrong in a bigot’s life and they don’t have the power or the money or the agency to fix it, they’ll blame it on some secret community that has more power than they do.”

(Badham writes in her book that in 2020 a large group of QAnon believers drove illegally from Queensland to protest the Covid lockdown of Melbourne’s public housing high-rise towers, filming themselves and expounding their theories as they went. At that time, after the US, Britain and Canada, Australia was the fourth largest producer of QAnon internet content worldwide.)

Radical conspiracy theorists are often thought to be from the economic underclass with little opportunity for education, but Badham’s research revealed a different profile. She said: “In Australia I joined several groups undercover and the people I found were very much of the frustrated entrepreneur class, often successful small business owners who weren’t able to adapt in the pandemic and started blaming other groups – like women or Jews – for that.

“The big question now is can people be pulled back from these positions? And the good news is that yes, they can. There are a lot of internet cult survivors who travel and share their experiences and how they got out of their situation. The key to bringing people back is socialisation, letting people know you are there for them, but not to judge them.”

QAnon and On: A Short and Shocking History of Internet Conspiracy Cults by Van Badham, published by Hardie Grant, is available at good book shops.