While many Australians still pause for a minute’s silence to remember the fallen of the Great War of 1914-18, the “war to end all wars”, every year at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, since making a study of our local history, I choose on Remembrance Day, today, to also reflect on what I regard as the birth of an inclusive community in the newly-minted Noosa Shire.

It’s a story that begins at the turn of the last century, in the Lebanese town of Raas-Baalbek, when young Nahum fell in love with a girl called Etore, whose parents advised her to flee the hardships and violence of the Ottoman Empire and make a new life in faraway Australia.

Nahum’s parents agreed and provided a willing uncle to chaperone the young couple on the long sea voyage. Within days of their arrival in Melbourne, they were married in St Patrick’s Cathedral, and soon after sailed for Queensland.

By the time they reached the Gympie goldfields in 1906, they had basic English, had anglicised into Ted and Edith, and had started a family.

On the goldfields, Ted formed a friendship with another miner, Ned Ely, whose father Bill had followed the path of several Gympie miners who had made good, and resettled the family on the banks of the Noosa River.

Ned painted such an appealing picture that Ted was soon sold. Soon after third child Maisie’s birth, the growing Massoud family moved to Gympie Terrace.

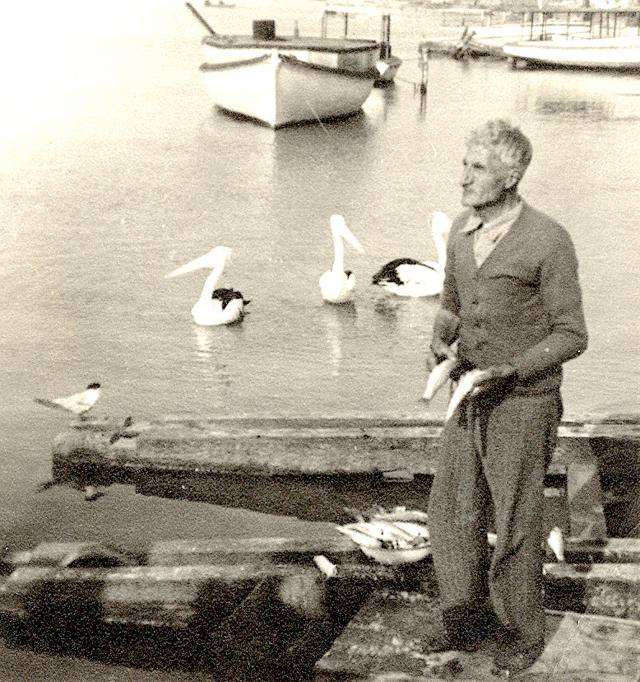

Here, over the years to come, the patriarch and matriarch would become better known to their small community as Jiddy and Sitty — Arabic for grandpa and grandma.

With several mouths to feed, the Massouds began fishing, and generally caught enough to sell a few fillets in their general store on the riverfront. At first they caught bream at night on lines, then progressed to nets to haul in large mullet catches.

After Jiddy bought a boat called Riverlight early in 1914, the family had to hire staff to help out with their fast-growing river enterprises.

In business and in community affairs on the Noosa River, the Massouds were only just getting started when Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary was assassinated in Sarajevo in June 1914, setting off events that would culminate in World War I.

In the coming years, the Massoud homeland of Lebanon, nominally allied with Germany as part of the Ottoman Empire, would be caught in the Middle Eastern crossfire and see half its population starved to death as supply lines were cut off.

We don’t know how much of an impact this had on the stolid Jiddy and Sitty when Australia entered the war as a member of the British Empire, and local boys began enlisting for the “grand adventure” that would see so many slaughtered on the beaches of Gallipoli and on the Western Front.

Since their culture had been subsumed by the Ottomans, many Lebanese in Australia (known until the 1940s as Syrians) had little or no political affinity with their homeland, yet they were technically the enemy. Even while Jiddy and Sitty raised funds for the Noosa Shire Patriotic Appeal, hundreds of equally patriotic migrants were being herded into a hastily built internment camp next to the Enoggera Army Barracks in Brisbane.

Lebanese–Australian historian Dr Anne Monsour, whose grandparents came from the same village as Jiddy and Sitty, and who is related by marriage to the Noosa clan, wrote of the situation: “For Lebanese families in Australia, the First World War exacerbated their experience as outsiders and reminded them their acceptance was tenuous … In October 1914, the Commonwealth Parliament passed the War Precautions Act. As Turkish subjects, Lebanese were declared enemy aliens and placed under surveillance”.

Many Lebanese were interned for the duration of the war, but to the eternal credit of the new Noosa Shire, the hard-working, community-minded Massouds were among the new settlers who were protected from the authorities.

Noosa was not slow to answer the call to duty.

By February 1916, the shire chairman was able to report that more than 200 men from the shire population of 2000 had volunteered for the front, with many casualties and several deaths (by the end of the war, it would be 350 injured with 40 dead). On the home front, more than £3000 had been raised for the Patriotic Fund, a thousand of it on one day, with Jiddy Massoud and older sons George and Bill prominent among the fundraisers.

Then finally, on 11 November 1918, peace.

In Noosa Shire a week-long celebration culminated in a torchlight Saturday night procession through the streets of Tewantin to the green beside the 400-year-old fig tree, which had been a meeting place for the Kabi Kabi for several hundred years before the arrival of the Europeans.

The civic fathers and business leaders gave thanks for the end of hostilities and paid homage to those who had made the supreme sacrifice.

Last but one to speak was Ted Jiddy Massoud, who stood proudly in the warm night air with his work shirt buttoned to the neck and his hair neatly slicked down, and, representing his extended clan and the fishing fleet of Noosa, gave thanks for the tireless work of the entire community — one they now called their own.

Adapted from Place of Shadows, available at philjarratt.com