As Noosa Sound turns 50, with waterfronts fetching $20m, PHIL JARRATT looks back on its rather shaky beginnings.

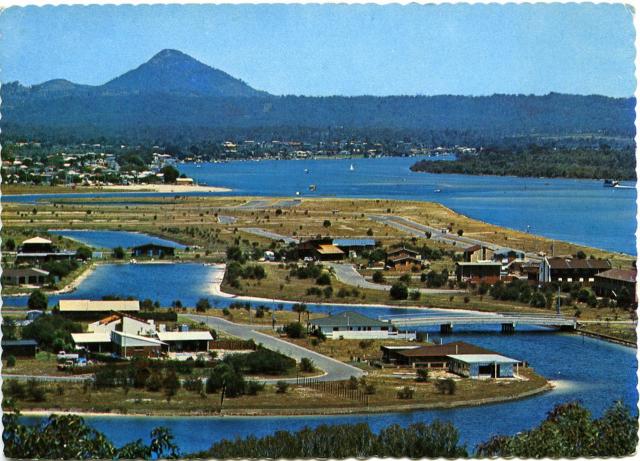

Judging by the fading black and white photos from Tewantin’s Griffith Studios, it wasn’t exactly a huge spectator event when Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen stood behind a monument set on a lonely and dusty paddock built over the mangroves of Hay’s Island and declared Noosa Sound officially open 50 years ago next month.

In the heat of early summer, gentlemen removed jackets – some dared to sport combos of crotch-hugging Bermuda shorts and socks – while the ladies sheltered under sun umbrellas and the small crowd listened to interminable speeches from the likes of Cambridge Credit Corporation’s managing director and chief executive officer R.E.M. Mort Hutcheson as curtain raisers for Premier Joh’s quirky and animated keynote address.

Despite the low-key optics, it was a momentous day for Noosa, the start of a new era of residential and tourism development, and an ominous one for Mort Hutcheson who, before the building of the bridge across Weyba Creek at the other end of the Sound was completed the following year, would have presided over the most sensational corporate collapse in Australia’s history to that point.

Even as the developers high-fived and glad-handed each other on that December day half a century ago, it was becoming clear that Noosa Sound had been built on shaky ground in more ways than one.

The Sound, the first major development that would change Noosa’s future, and ultimately pit the “progressives” – as the pro-development lobby liked to be known in those days – against the environmentalists in a long and ongoing battle over the integrity of the Noosa River system, had its origins back in July 1946, when newly-elected Noosa councillor Edgar Bennett proposed the building of a bridge from near Hastings Street to Hay’s Island, as a first step to stabilising and later developing the river’s mangrove swamp islands.

Bennett also proposed a coastal headland road skirting the soon-to-be-declared national park. The headland road idea would rear its ugly head many times in the future and fortunately never happen, but the reclaiming of Hay’s Island would stay on the radar over the next two decades before becoming a 1970s reality.

In 1964 two separate proposals put to council seeking approval for residential development on Hay’s Island were rejected, but in 1966 the department of Harbours and Marines, according to Cambridge Credit’s Hutcheson, “made very detailed studies and decided that Hay’s Island was suitable for development”.

Three years later a new council approved a proposal from a company called Noosa Island Estates, which was soon revealed to be a front for Australia’s biggest land developer and financier, Cambridge Credit.

The proposed development was massive. It involved clearing the mangroves, dredging sand from the river to raise the land level by a metre, and the building of three bridges. It was expected to take five years to complete, with blocks of land then being offered for up to $10,000.

The tender was officially accepted in September 1970 by the hard-drinking Minister for Lands, Vic Sullivan who tossed a few down before the official announcement at Brisbane’s Park Royal Motor Inn and declared loftily: “Most of the area… is an unsightly combination of mangrove swamps, mud flats and sandbanks… the main breeding grounds for mosquitos and sandflies”.

The theme of mosquito infestation continued when Premier Joh and Cambridge’s Mort Hutcheson shared the podium on the dustbowl of the clear-felled island on 17 December 1973. Announcing a gift of 40 shrubs for each buyer of one of the 140 $12,000 blocks on offer, Hutcheson said: “I like to compromise between man and nature, and although nature comes first, man requires to enjoy it… so I don’t apologise for taking it away from those mosquitoes and sandflies.”

Later in his address, Hutcheson made reassuring noises about the F-word – flooding: “We’ve commissioned numerous surveys with particular reference to flooding… and for all those people who were a bit concerned and such like, well there’s no worries here whatsoever.”

A month later Cyclone Wanda ripped down the coast and devastated Main Beach and The Woods camping area, and flooded parts of Noosaville and Tewantin.

Lawyer Bob Cartwright donned his wet weather gear and went to inspect the damage. He recalled: “On the Sound, about 100 metres along, just opposite the Woods, the river level was so high it was lapping the top of the new retaining wall, and when there was a set or a surge from the ocean, ripples would break across the road, and wash out holes in the gravel. There was no doubt that it was in danger.”

The immediate bandaid came in the form of the Mineral Deposits sandmining company, which had mining leases on Noosa’s lower North Shore, with a procession of tip trucks barging across the river and diverting to Noosa Sound every low tide, where the heavy, mineral-rich sand would be packed into the cracks and holes.

But when the problem worsened after Cyclone David two years later, the Bjelke-Petersen government in its wisdom decided that a long-term solution could be found through a “retraining of the river mouth” and lengthening of the Spit by half a kilometre to screen the Sound from ocean swell, thereby creating an environmental disaster, the consequences of which we are still grappling with today.

The monumental $1.4 million cost of this was mostly shared by the state and Noosa Council, the developer, Noosa Island Estates, having disappeared like sand through the cracks of Noosa Sound, with its parent, Cambridge Credit, soon to follow.

But let’s get back to happier times, and that stinking hot morning in December 1973, when Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen finally gets his turn at the microphone.

The Premier continued the almost Biblical theme that “a former pest-infested area” had been miraculously transformed into a “beautiful housing estate”, before launching into an endless paean of praise for the courage and financial acumen of Hutcheson and Cambridge (“an organisation of high repute”) for juggling nine major development projects worth $175 million.

It would be another nine months before Cambridge Credit’s record collapse with liabilities of $190 million left 38,000 investors in the lurch, but in the canyon of O’Connell Street in Sydney’s financial district rumours were already flying that if the Whitlam government’s spending spree brought on the credit squeeze that many were predicting, the debt-heavy Cambridge house of cards would be among the first to topple. Was Joh providing cover for a mate in trouble?

Who knows, but in winding up his long address he said: “One of the project managers said to me this morning, ‘It looks all very well now, but there were many times through the project we wondered how much money we were going to lose in this tremendous undertaking.’

“I’m afraid many people overlook these factors… they fail to appreciate the courage and risks involved in so many of the undertakings we see before us today. And so we say congratulations to you, Mr Hutcheson, and to your organisation.”

And so say 38,000 investors who lost their shirts!

Happy 50th, Noosa Sound.

Parts of this article were adapted from Place of Shadows, by Phil Jarratt. Signed copies available from philjarratt.com