David Marr’s brilliantly researched Killing For Country is not an easy holiday read, but poolside in the shade of the palms (ahead of our big wet) is where I’ve devoured the concluding chapters.

I’m not ashamed to say I frequently had tears trickling through the sun-cream, and on a couple of occasions had to immerse myself in the cool, clear water in some foolish attempt at cleansing the shame, not so much of murderous ancestors (unknown in my case) but of the turgid, apologist prose of my journalistic forebears over more than half a century of the attempted ethnic cleansing of Queensland.

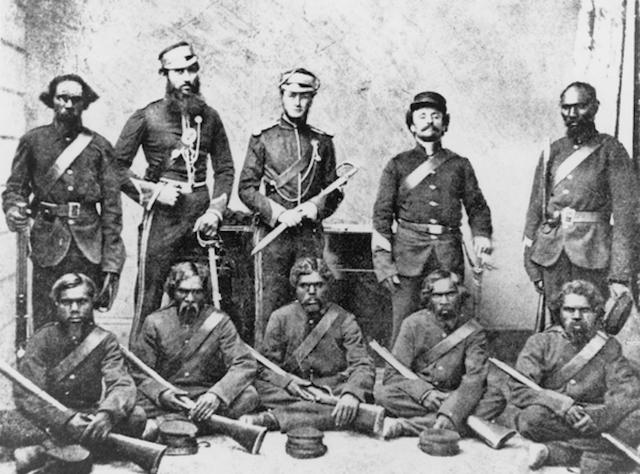

Marr’s book, subtitled A Family Story, uses the premise of discovering documentation of his great-great- grandfather Reg Uhr’s service in the disgraceful Queensland Native Police as a ramp into the broader story of “dispersal” in colonial Australia, but his greatest strength is the power of his research, which reveals, in layer after layer of contemporary accounts, the cowardice of government in not stopping the officially approved slaughter of First Nations people, the abominable behaviour of media organisations in reporting it gleefully like some kind of boy’s own adventure, and the squatter-led public who lapped it up.

Having researched the frontier wars for years, written about them in several books and many articles, and having devoured the work of historians like Jonathan Richards and Henry Reynolds, I came to Marr’s book with a better than average understanding of what happened in Queensland over the greater part of the 19th century, but what bowled me over was the horrific detail, often using multiple accounts of murders and massacres to build an unbearably graphic picture. As First Nations academic and campaigner Marcia Langton put it: “This book is more than a personal reckoning with Marr’s forebears and their crimes. It is an account of an Australian war fought here in our own country, with names, dates, crimes, body counts and the ghastly, remorseless views of the settlers.”

Although Marr was guided in his research by the Killing Times massacre map and database established by the University of Newcastle, which includes a verification of the Murdering Creek massacre on Lake Weyba, the closest he gets to the work of the Native Police in our region is in the Wide Bay and Burnett, which is perhaps understandable, given the scope of their bloody undertakings there and elsewhere. But I was pulled up time and again by detailed telling of stories of which I knew a little, and this was particularly so as the author tracked Reg Uhr and his equally murderous brother D’arcy further north, to Bowen, the Burdekin, the Valley of Lagoons and finally to the South Wellesley Islands of the Gulf.

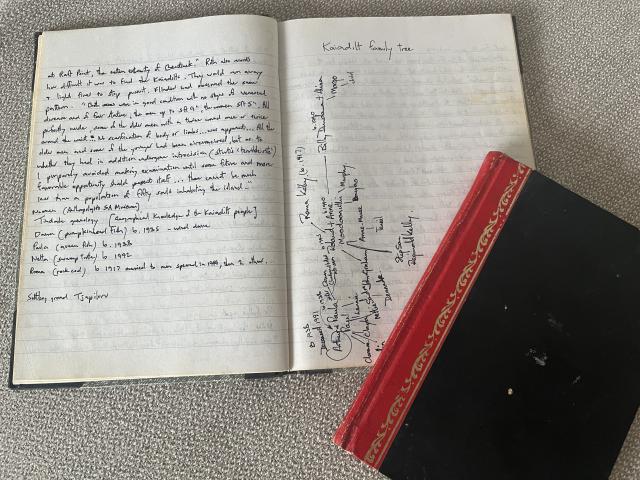

In the late 1980s and early ‘90s I spent a lot of time in the remote parts of Queensland, seeking out stories of squatters and traditional owners, mostly – and somewhat ironically – for The Bulletin magazine, whose masthead from inception in 1880 to the early 1960s carried the motto, “Australia for the White Man”. Fortunately that had been removed, along with the racist dogma that often accompanied it, 25 years before I began bush-bashing for The Bully, but flipping through the old magazines I was surprised to find how infrequently my articles touched on the ugly truths of outback Queensland in colonial times. But my longhand travel notebooks (never took a computer, or even a typewriter bush in those days) tell quite a different story. This was never more evident than in the copious pages of notes of my travels around the Gulf of Carpentaria and to the South Wellesley Islands of Sweers and Bentinck in 1989 and ’91. I wrote so much and yet so little found its way into print.

David Marr tells the story of his great-great-grand-uncle D’arcy Uhr deserting his post at the fever-plagued (possibly malaria) settlement of Burketown for the cleaner sea air of Sweers Island in November 1866, where he and the explorer and magistrate William Landsborough, who had set up a hospital camp for evacuees, took an open boat the couple of kilometres across Investigator Road to Bentinck Island, home of the Kaiadilt people. On Bentinck Landsborough left D’arcy with his two Native Police troopers while he set off to cross the island on foot.

He later wrote: “Before we had gone far we heard the discharge of a gun and thought it was merely discharged at some cockatoos we could see in the distance. I was sorry to learn however from Mr Uhr that the blacks had rushed towards him with spears and he had to discharge the carbine at them. I am sure Mr Uhr would not have fired upon them if he could have avoided it.”

A short time later D’arcy returned to Bentinck with a stockman named Michael Bird Hall, who was so appalled by what happened there he spent years trying to have D’arcy prosecuted. He wrote: “They found a Blacks camp, rushed it and sequred (sic) two small boys between eight or 10 years of age … and conveyed them to the boat followed by the supposed parents crying for their children … Mr Uhr brought them to Swears (sic) Island … ironed together to keep them from escaping … I have often seen these poor children beat for only going down to the beach opposite Bentinck Island.”

As Marr explains, it was commonplace for young Aboriginal boys to be “rescued” or “saved”, often after their parents had been slaughtered by the Native Police, and sold as slaves for money or grog. This was one of his descendant’s grisly stocks in trade.

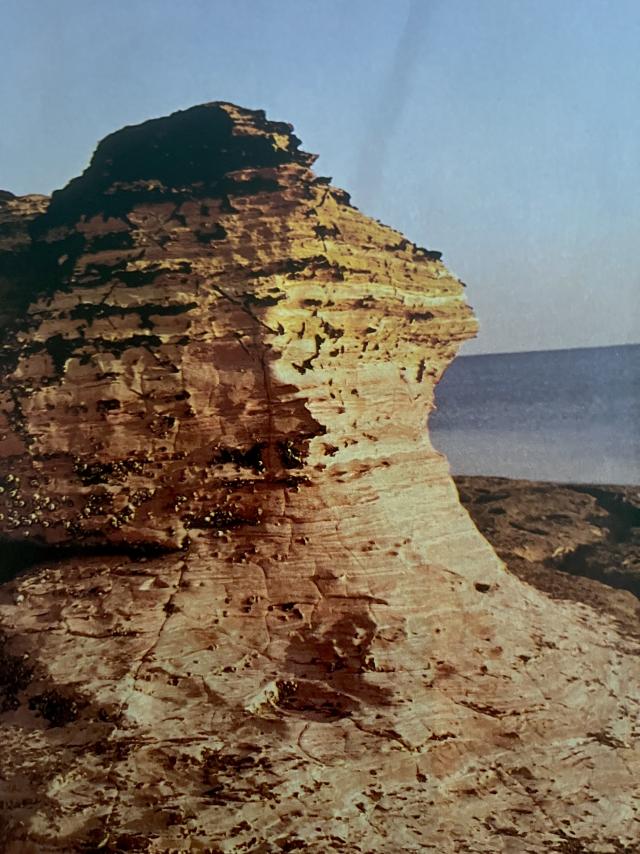

The twin islands of the South Wellesley group were discovered and ignored by Abel Tasman in 1644, who gave a passing nod to Saloman Sweers, the member of the Dutch East India Company council of Batavia who had signed his exploration orders, by naming the nearer island for him. They continued to be ignored by all but pirates and castaways, even by the Macassans who sometimes passed them when blown off their more westerly trade route. In 1802 Matthew Flinders anchored his sloop HMS Investigator off Sweers and camped on the island while his men caulked the ship’s hull before continuing their circumnavigation of Australia. In 1841 John Lort Stokes, commander of the exploration vessel the Beagle, camped on Sweers and discovered a tree on which Flinders had carved the name of his ship. Stokes carved the name of his own boat, beginning a tradition for the Investigator Tree.

Stokes was so impressed with his anchorage and its surrounding islands that he wrote in his journal: “We might look forward to the time when Investigator Road should be the port from which all the produce of the neighbouring parts of the continent must be shipped and when it should bear on its shores the habitations of civilised man.”

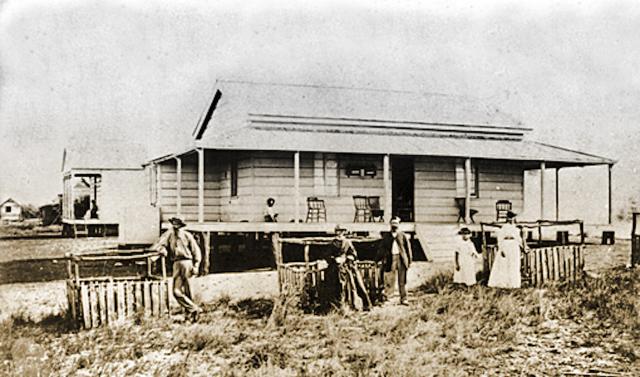

But Sweers was not destined to become Singapore or Sydney, being used only as a base for crisis management by Landsborough, first in 1861 to co-ordinate rescue attempts for the doomed explorers Burke and Wills, and again in 1866 as a haven from the fever that was wiping out the population of Buketown. Landsborough used his time in the Wellesleys far more productively than Uhr had, mapping out and commencing the building of a settlement he called Carnarvon.

Carnarvon soon had a pub, a store, a lockup and a “customs house”, but it was too remote to stand a chance, particularly after the administration office for the Gulf and Cape York was moved back to the mainland at Normanton. But it continued to be used as a temporary base for geographers and anthropologists, none of whom had much luck communicating with the shy Kaiadilts, considered the least known of all coastal Aboriginal groups, which was why Sweers and Bentinck were visited by Dr Walter Roth, Northern Protector of Aborigines, based in Cooktown, in 1901. Although they ran away every time they saw him coming, Roth gave the Kaiadilts a glowing report in terms of their health and self-sufficiency, noting their “good condition” and their intricate and successful “fish dams”. Roth was a great advocate for allowing the Kaiadilt people to be left alone with their traditions. But he soon moved on to a higher anthropological calling and wasn’t able to protect them from a brute named John McKenzie, who in 1911 had secured a lease to run sheep on parts of Sweers and Bentinck. He built a hut on Bentinck and took to riding around the island on horseback, shooting at every Kaiadilt he saw, except the girls he intended to rape. The anthropologist Dr Norman Tindale estimated that McKenzie had killed at least 11 Kaiadilts during his reign of terror.

In October 1989 I drove past the Fred Walker monument at Floraville Station, near Burketown, not realising that it honoured the bloodthirsty first commandant of the Queensland Native Police. With photographer Paul Wright I was on my way to Escott Barramundi Lodge and airstrip to meet up with a bloke I had met in the bar of the Albion Hotel in Normanton about a month earlier, a fellow who promised he would bring history to life for me.

Tex Battle and his Irish wife Lyn had recently taken up a leasehold on Sweers Island and created a fishing camp, a string of very basic dongas on the site of the settlement of Carnarvon, overlooking Investigator Road, and were waiting in a Cessna to take us there. Over this and subsequent visits, I would lie on the beach at Bentinck with the Kaiadilts on clear nights, watching the space junk pass by and listening to their lived history, tales passed down the generations which revealed that although their spirit prevailed, their misery did not end when John McKenzie left the islands in 1918.

Next week: Morning Glory and meeting the Kaiadilts.