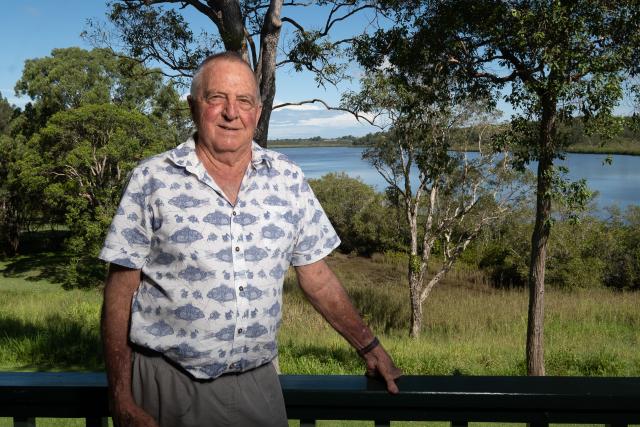

On a rare sunny afternoon last week Dr Geoffrey Bowden made himself comfortable in his favourite deck chair, looked out across the trees and mangroves to the magnificent expanse of Lake Doonella and said to his guest: “Until a month ago we had 100 black swans out there, the most we’ve ever seen.”

After more than 50 years looking at this view from the house he and wife Carolanne built in 1971, there was still a touch of wonderment in the voice of the octogenarian as he described in great detail the workings and natural wonders of the shallow lake that might not be his, but for which he clearly feels that he is a guardian. Not fussing or stressing, just quietly overseeing its maintenance and offering advice.

To be honest, I had expected the meeting to be somewhat adversarial, since I had written several articles presenting the views of the Tewantin community group who want to see a public walkway created along the western shore of the lake.

The good doctor (retired 1997) had written to me complaining about the “disinformation campaign which has sucked you in apparently, and [created] a lot of stress for my neighbours.” But after a brief dance around the issues, we were settled on the balcony and were amicably swapping fishing stories.

“Before my time here the lake was full of mud oysters and mud crabs, but the oysters were wiped out by over-harvesting,” he said.

“Still the odd mud crab though.”

He continued his education of the writer with enthusiasm.

“The strange thing is the swans. I reckon they’re like the pelicans at Lake Eyre.

“They know when the feed is here from the weather conditions over months. Apart from the green stuff around the edges, they like [to eat] the ribbon weed which only grows in the salty water. When we get a lot of fresh, like now, it bowls it over.

“The best bird time here is winter, when everything is calm and boils of prawns come out of the creek. Then we get cormorants and pelicans. The jabiru only come when the water is really smooth and when it’s a certain depth, usually early morning. We only get one or two, but they’re amazing to watch, the way they dance around chasing the fish until they can grab it with their beak and put a foot on it while they eat it. But we can go three years and not see a jabiru.”

Born and bred in Brisbane, Geoff Bowden was a frequent visitor to Noosa in his early years, but after graduation and a couple of years at Royal Brisbane, he and mate Des Milliner headed west. Des went to Blackall while Geoff became hospital superintendent at Hughenden.

“Actually I was the only doctor for many kilometres in all directions,” he said.

“At 25 it was quite a responsibility.”

Des Milliner didn’t last as long in the bush as Geoff, and in 1968 he moved to Noosa where he and a partner bought out the Noosaville practice of Dr Arthur Harrold, co-founder of Noosa Parks Association. But in 1970 Des phoned his friend and explained that the partner had gone “a bit troppo”. Would Geoff like to come to Noosa and join the practice?

Within a few months Geoff and Carolanne and their three young children had moved to Noosa and found a large, skinny, sloping block that stretched from Poinciana Avenue down to Lake Doonella. I asked Geoff to describe what he saw, and we both stood up to better take in the scope.

“There were cattle grazing over on the other side where the she-oaks are. It was just beautiful, looking down on the lake and beyond. Wifey marched down the back here, stood on the bank and said, this’ll do!

“The story goes that the stage coach used to go through my land coming down from Cooroy. There was a little cottage up the front near the road but it was on this big long block going back to the lake, and that’s what interested us.

“We initially only had one block wide but we asked the bloke next door if he’d sell, and he walked us up the hill as far as he was willing to sell and we amalgamated that into ours. Over the years we’ve added another two more pieces. Now we’ve got nearly two acres.”

The Bowdens commissioned a house from Job and Froud, the Noosa architects du jour who had a showroom on Hastings Street and whose trademarks were cooling breezeways and big verandahs, and when the large and airy home was finished it featured in all the papers. But there was just one hitch.

Noosa Council had planned and surveyed a major thoroughfare to run along the western shore from the Doonella Bridge to St Andrews Drive, and land resumption orders were already in place.

Geoff took up the story: “We more or less thought we were stuck with it. There was no resumption order on our property because the road would be over water, but most of the properties from Moorindil Street to the bridge had resumption orders on them because the plan was for the road to cut across the land at that point. At least one friend of mine made them pay up once the order had been made and he got $40,000 and then got his land back when they abandoned it.

“In the end we didn’t have to fight, it went away by itself. They would have had to build a big rock wall and destroy all the mangroves, and they realised that all it would be doing was sending traffic into Noosaville and creating a bottleneck with nowhere to go.”

I asked Geoff how he would have felt if the road had gone ahead.

“We would have learned to live with it,” he said.

Despite the heavy workload he shared with Des Milliner, being the only GPs between Coolum and Tewantin throughout 1971, with rooms in Hastings Street, Noosaville and Tewantin, Geoff made time to spend on the lake with his young family.

“I’ve walked across this lake with a kid on each hand and pulled up with a big stingray in front of me,” he recalled, pausing to reflect on a cherished memory.

“You just splash the water with your foot and they’re gone.”

He meant the ray but we were both thinking about our grown kids.

One of their neighbours was a retired fisherman and he lent the family his net boat. Said Geoff: “He had a pathway through the mangroves and on the other side he had his net boat pulled up on these sloping poles to keep it away from the worms. The mangrove roots have taken it over now.

“We’d row across and put pots in or take the kids for a ride and our labrador would swim behind. The kids all loved it.

“We sailed Hobie Cats on it, and when you got one on its edge on a big tide, the rudder would be scraping the bottom.”

Many years after the planned vehicular road was abandoned, then Councillor Olive Macklin proposed a pathway along the edge of the lake beside the mangroves.

The lakefront residents objected strongly.

Geoff Bowden recalled: “There are dozens of different species of mangroves but the tight little ones we have here, you just cannot build a pathway through them. It was costed by council and it was estimated at over a million dollars, so it never went any further.”

Geoff sees parallels with the current advocacy for a pathway, although as this writer understands it, what is proposed is a path along the grassy bank.

He said: “They haven’t specified what kind of walkway they want but the group is demanding an immediate result, not understanding that the area is within the intertidal zone so you have to go through government planning, as the sewerage line had to. The upshot is the council is going to kick this issue so far down the road it’s never going to happen.”

He continued: “A slasher appeared one day on my fence-line and slashed along my boundary and disappeared. Next thing they all start walking up and down to create a pathway, people, kids, dogs. Luckily for them, the tides were low at that time or they would have been wallowing through mud. That’s when it got confrontational.”

Although that has now calmed down somewhat, the issue still simmers around Tewantin.

I asked Geoff, given that he said he could have lived with a road between him and the lake in the 1970s, how we would feel if a pathway was allowed.

“I’ll be dead by then,” he laughed, and then continued more thoughtfully: “I’d have to accept it, but what is it going to achieve?

“At mangrove level, they won’t see water, but often they’ll be walking through it. Would I go to court to stop it? No. I’d just suggest that councillors see a psychiatrist.”

![[READER COMPETITION] – Win a family ticket to Hudsons Circus](https://noosatoday.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Hudsons-circus-1-100x70.png)