Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories.

Walter Benjamin (philosopher)

When collector Gary Clist was running around the grounds of the Cooroibah property he shares with wife Yoko in the middle of Good Friday night in a desperate hunt for hoses that might prevent their house burning to the ground, the last thing on his mind was saving the precious collectibles inside.

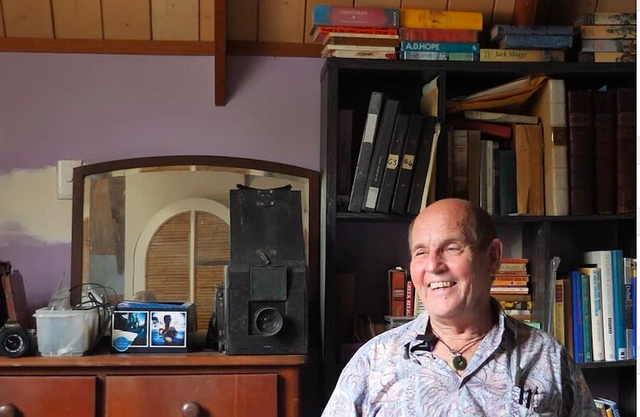

This was a battle for survival, of themselves and their wooden house, but since that dreadful night he has thought of little else. As an avid collector myself, while somewhat understanding his and Yoko’s preparedness to submit to the will of their Lord and simply move on with their lives, I completely understand Gary’s heartbreak at the treasures which have been lost. There are many long-time residents of Noosa who know of one or even two of Gary’s collectible passions – the surfboards and kneeboards, the rare antique bibles, the vintage cameras, the historic postcards, the record albums, the first edition books, even the ancient Roman antiquities, but not many have been privileged to observe at close quarters, as I have, the scope of this passion for finding, filing, and sometimes forgetting so much stuff.

As Georges Rodenbach, the Belgian poet and novelist wrote in The Bells of Bruges: “Is this not the collector’s exquisite pleasure, that his desire should know no bounds, should reach out into the infinite, should never know full possession which disappoints by its very completeness. O what joy to be able to postpone the fulfillment of desire to infinity!”

There’s not a lot of joy over this postponement of fulfillment right now, but the Clists are nothing if not resilient.

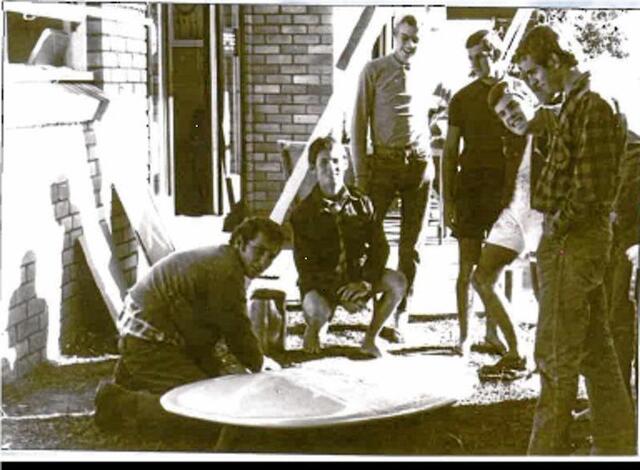

Not quite Noosa “First Fleeters”, the Clists have nevertheless been around a long time, and over two generations they have established themselves in the community as fair traders in business and generous workers for charity. Originally from New Zealand, George and Juliet Clist migrated with their two young children to Sydney’s northern beaches in the 1950s, where Gary developed a lifelong love of surfing and a love of cameras when he scored an after-school job at John Stone’s camera store in Avalon Beach. George was a restless man with an entrepreneurial spirit who had survived four years as a WWII prisoner of war. Always looking for the greener grass, in 1967 he brought the family to Noosa where he took the freehold on the Noosa Park Inn on Mitti Street, opposite the gates to the national park, renaming it the Noosa Wave Kiosk, soon a magnet for hungry surfers.

Unable to fit into the tiny attached flat, Gary took in Noosa life and the magic of the waves rolling along the points from a caravan parked at the end of the then-dead-end street. Soon he was as passionate about photographing the waves as he was about riding them on his preferred craft, a kneeboard.

After finishing school, Gary was conscripted for national service, but when he returned to Noosa in 1973, he decided to give the wheels of commerce a spin, literally alongside his dad, who had sold the kiosk and gone into retailing and real estate. They had adjoining space in the new Tingirana Arcade on Hastings Street, from which Gary turned his passion for photography and music into Clist Sight and Sound Centre, selling film for the camera and cassettes for the car. This was the start of a retail career that would take him to premises in Noosa Junction and Tewantin, all the while building his personal collections through contact with the shire’s growing creative community.

In one of his Tewantin shops, there was room to build a tiny studio and darkroom, so Gary morphed into a part-time commercial photographer, which brought him into contact with many of the old local families who would complain about the clutter of boxes of old photos, postcards and magazines left in the spare room by the previous generation. Gary would gladly relieve you of any of this “rubbish”.

Decades later, when I was researching a book on Noosa’s history, Gary would generously guide me through dozens of such boxes, gathering dust in the Cooroibah home, until we had found the key that opened vaults of a little-known past, through this old pile of postcards or that old file of negatives or crumbling tourist maps. What I have always liked and valued about his approach to history is that no fact or theory, photo or news cutting is too trivial to be ignored. This is our history writ small, and I love the contributions he has made to the FaceBook page Who Remembers Noosa Before It Was Cool? (See sidebar It’s the little things.)

Gary and I pull a couple of old chairs from a pile and set up in a shady corner of the car park of the Salvation Army shop, where he and Yoko volunteer a couple of days a week. It’s five days after the fire. I ask him how it feels to lose so much. He sighs deeply and wipes a tear away. “There’s a monetary value, of course, but It’s the things that you’ve waited so long to get, like the Greenough spoon.”

It’s interesting that such a committed Christian would reference a 60-year-old kneeboard over a 1679 King James Bible in near mint condition, but vintage surfboards were what first brought Gary and me together. He continues: “As a kneeboard collector I always wanted one, but any genuine George Greenough, actually built by him, was way out of my league, but I managed to buy a Hayden spoon in the US and get it shipped here. I was hoping it would be one of the export models with a made-in-Australia tag on it, and was a little disappointed when it didn’t have that, but it was a nice board.”

The back story here is that the eccentric American genius Greenough – still living in Byron Bay in his 80s – revolutionised kneeboard (and ultimately surfboard) design in the mid-1960s while working with Hayden Surfboards on the Sunshine Coast, but he was too busy surfing the Noosa points to fulfil orders so the shaping very quickly fell to surfboard craftsman Terry McLarty.

Says Gary: “I took the board down to Terry at the factory to get him to sign it, but he picked it up and felt the rails and said, ‘Mate, I didn’t make this. George did.’ I had my Greenough spoon at a fraction of its value! Unbelievable. It was in the bedroom where I kept the best of the best, next to the Joe Quigg balsa bellyboard I got from you. Both gone now.

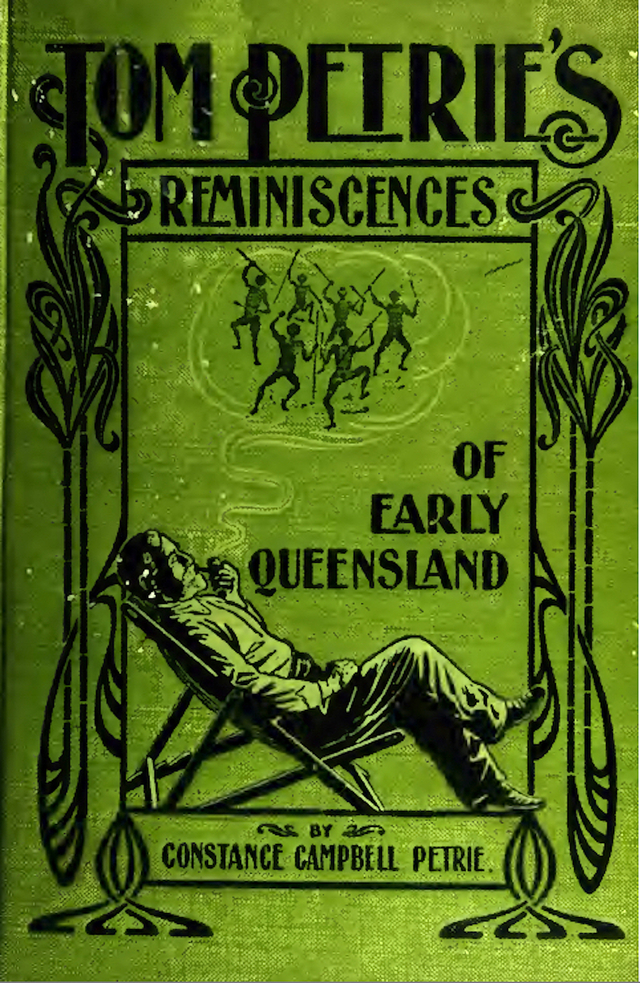

“The really valuable books, like the King James Bible, were up there too. I’d just found a little glass-paned cabinet at the tip and fixed it up nicely to display that and some other bibles from the 1830s, plus the first and second editions of Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland, from 1904 and 1933. All gone.”

Gary Clist is close to tears again, but I sense that talking about the loss is therapeutic, and he keeps remembering more of it. “More than 200 vintage cameras reduced to rubble. My original edition hardcover Gidget, signed by Frederick Kohner and Gidget herself! Another one I got through you – Duke Kahanamoku’s personal airline bag with signed photos … and …”

There’s so much more that I need to change the subject. Will he start another collection?

Gary looks into the middle distance and says quietly: “I’m not planning to start collecting again now at my age, but collectors always collect, with or without a plan.”

![[READER COMPETITION] – Win tickets to the Queensland Ballet at The J Theatre](https://noosatoday.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Queensland-Ballet-100x70.png)