As we start to see the $9 million upgrade of Noosa Parade take shape, it’s worth reflecting that it’s 50 years ago this month that work on the original $3 million, 300-homesite canal development, that changed Hay’s Island into Noosa Sound, began with the building of a concrete retaining wall around the mangrove swamp island.

A cynic might note that you got a lot more bang for your million bucks back in those days, especially when you consider that the current upgrade is a zero sum game, trading off a bit of nature strip for a bit of bike path, or vice versa, but ending up with exactly the same shared space that we had.

It’s also worth noting that when the upgrade went to community consultation five years ago the price tag was a mere $3-5 million. But no one questioned it back then so let’s not fret about it now, when it’s a lot easier to reflect on the mistakes of the more distant past.

Noosa Sound, the first major development that would change Noosa’s future, and ultimately pit the progressives – as the pro-development lobby liked to be known – against the environmentalists in a long and often ugly battle over the integrity of the Noosa River system, had its origins back in July 1946, when newly-elected Noosa councillor Edgar Bennett proposed the building of a bridge from near Hastings Street to Hay’s Island as a first step to stabilising and later developing the river’s mangrove swamp islands.

Bennett was way ahead of his time during the two terms he served as a councillor, and not always in a good way. Had he come a decade later Noosa would look very different today.

Over that ration card summer of 1946-7, Bennett also proposed the shire’s first dedicated parking lot and a coastal headland road skirting the soon-to-be-declared national park. The headland road would rear its ugly head many times in the future and fortunately never happen, but the reclaiming of Hay’s Island would be debated over the next two decades before becoming a 1970s’ reality.

In 1964 two separate proposals were put to Noosa Shire Council seeking approval for residential development on Hay’s Island. Both were rejected, but by 1969, the Ian Macdonald-led council took a different view and approved a proposal from a company called Noosa Island Estates, which was soon revealed to be a front for Australia’s biggest land developer and financier, Cambridge Credit, and its retail affiliate Inter-Capital Investments.

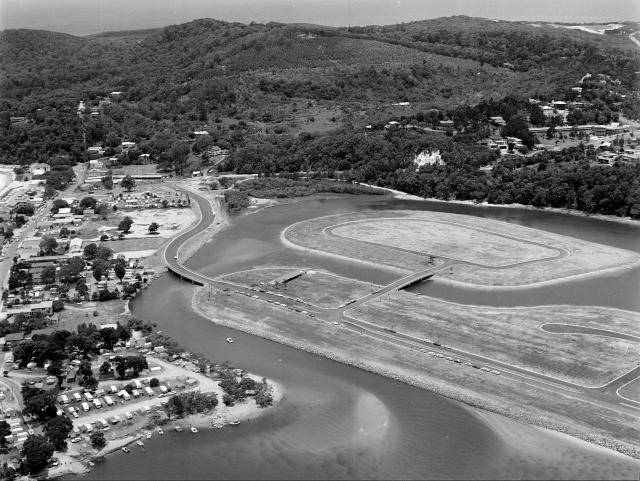

The proposed development, to be known as Noosa Sound, was massive. It involved clearing the mangroves, dredging sand from the river to raise the land level by a metre, and the building of three bridges.

It was expected to take five years to complete, with blocks of land then being offered for up to $10,000. The tender was officially accepted in September 1970 by the hard-drinking Minister for Lands, Vic Sullivan who tossed a few down at the official announcement at Brisbane’s Park Royal Motor Inn and declared loftily: “Most of the area… is an unsightly combination of mangrove swamps, mud flats and sandbanks… the main breeding grounds for mosquitos and sandflies.”

When work on the development actually began with the retaining wall around the island in August 1972, environmentalist and author Nancy Cato said opposition was confined to “several isolated voices raised in protest at the beginning, including those of local fishermen who feared the effect on fish stocks…”

Veteran solicitor Bob Cartwright remembers it differently: “There was a lot of fear and skepticism, particularly from the old hands in Noosaville, who thought the sea would roll right over it. Mind you, they weren’t too sure about Hastings Street either. As far as they were concerned it was a sand spit and not that stable.”

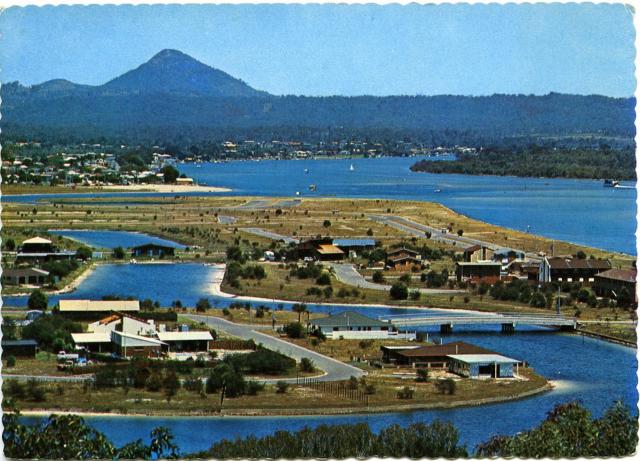

The first stage of Noosa Sound was opened by Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen in December 1973, with waterfront lots now being offered from $12,000.

Speaking to a large gathering of dignitaries and salivating real estate agents, the premier continued the theme that “a former pest-infested area” had been transformed into a “beautiful housing estate”.

A month later Cyclone Wanda ripped down the coast and devastated Main Beach and The Woods camping area, and flooded parts of Noosaville and Tewantin.

Bob Cartwright donned his wet weather gear and stepped out of his new law office in Noosa Junction to inspect the damage.

He recalled: “On the Sound, about 100 metres along, just opposite the Woods, the river level was so high it was lapping the top of the retaining wall, and when there was a set or a surge from the ocean, ripples would break across the road, and wash out holes in the gravel. There was no doubt that it was in danger.”

For some time, the Mineral Deposits sandmining company had been mining leases on Noosa’s lower North Shore, with a procession of tip trucks barging across the river and disgorging their loads day and night at the end of Moorindil Street, Tewantin, to await delivery to the processing plant across the NSW border at Cudgen. In the aftermath of the cyclone, these trucks would be diverted to Noosa Sound every low tide, where the heavy, mineral-rich sand would be packed into the cracks and holes.

But if the awesome power of the sea was endangering the new development before it really got started, an even greater danger was about to explode in the sunless canyons of Sydney’s financial district.

On 27 September 1974 shares in Cambridge Credit plunged by 80 percent overnight, signalling the most sensational corporate collapse in Australian history to that point.

Three days after the shares collapsed, Cambridge Credit’s board informed the stock exchange it could not meet quarterly interest payments due that day. The company’s liabilities were estimated at $190 million. The next day receivers were appointed.

Although court battles on behalf of its 38,000 investors would continue for 14 years, Cambridge’s decade of being a developer pretending to be a finance company was over. In the bigger picture for Cambridge Credit, Noosa Sound was almost collateral damage, but there were many locals who looked at the neat, empty, clear-felled estate leading to a dead end, and wondered, what now?

But at the end of 1974 the Weyba Creek bridge was finished, joining the Sound to Munna Point and Noosaville, and the moonscape slowly gave way to a desirable residential estate. I do, however, remember being in Noosa on a magazine assignment in 1979, and being invited to dinner at one of the new riverfront homes on Noosa Parade. It was very nice sitting on the terrace with a drink and looking across the inlet at the little hippie yachts and the old campground, but we were otherwise surrounded by dusty paddocks.

I remember thinking, why would you want to live out here on the edge of civilisation?

Well, people did.

In fact there’s one on the market right now for $21 million if you’re quick.