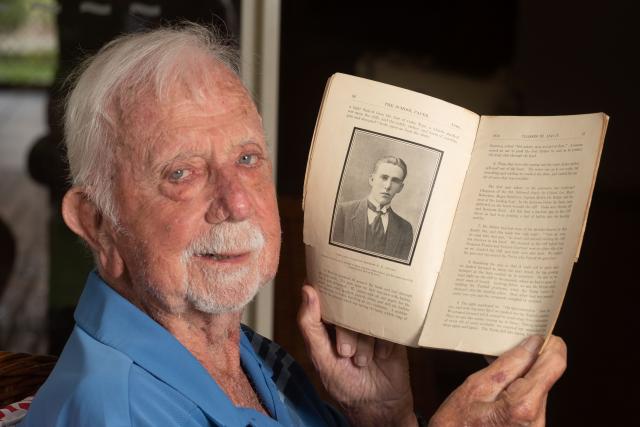

Ninety year old John Crossley was helping his teacher clean out a cupboard at Ithaca Creek State School on Brisbane’s Northside 80 years ago when he was attracted to a magazine with a colourful cover.

John asked the teacher what he was going to do with it and was told it would be thrown away.

“You can have,“ the teacher told him.

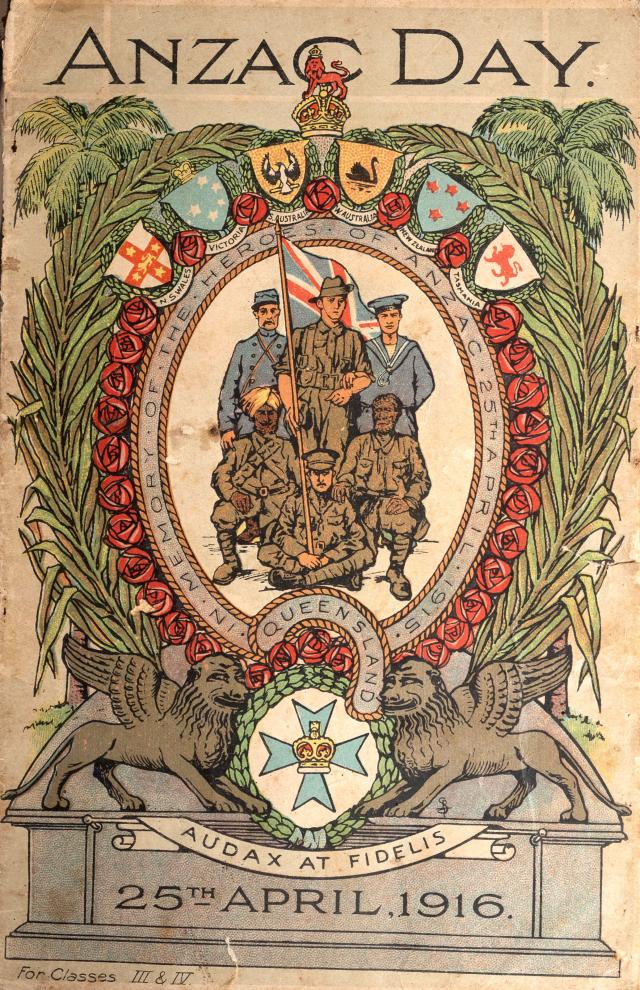

While tidying up at his Peregian Springs home the other day, he came across the small magazine dated 25 April, 1916. It was the first memorial edition of Anzac Day.

Inside he discovered a first hand account of the landing of Australian Forces A Company, 9th Battalion at Gallipoli on 25 April, 1915.

Here is that story:

After leaving Egypt the 9th spent eight weeks at the Island of Lemnos, the last three weeks on the transport Malda. On the 24th April we were told by Sir Ian Hamilton that the 9th had been chosen to make the landing for the 3rd Brigade, which was to be backed up by the 1st and 2nd Brigades.

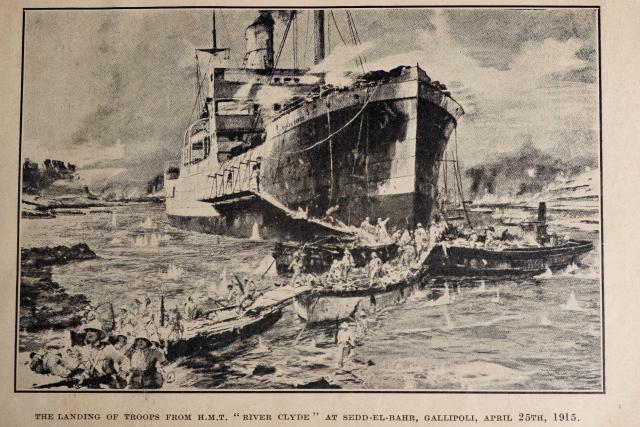

Filled with excitement, we bade farewell to the Malda and went on board the torpedo boat Scourge, which conveyed the battalion to HMS Queen. The warship steamed to Tenedos, and lay off the island waiting for night to fall. The crew treated us right royally and supplied us with three hot meals. At midnight we were assembled on deck, and clambered down the ship’s side to the boats below.

With as little noise as possible the boats left the side of the warship, and no one who was in those boats will ever forget the silent cheer the British tars gave to the Australians, as the boats drew away – a frantic wave of their arms, nothing more, but enough to assure us that the men of the British Navy were proud of their Australian brothers in arms, the 9th Battalion of Queensland.

With scarce a ripple our boats drew towards the shore. We were the first boat and about 50 yards from the landing when a light flashed from the fort of Gaba Tepe, a whistle shrilled out upon the cliffs and the rattle, clatter, and boom of machine gun shrapnel broke upon us from the shore.

Bullets splashed all around the boats and tore through the wood-work. The pack upon my back was torn with bullets, but I was untouched. We pulled with all our might for the shore; men cried, laughed, prayed, swore, and still the bullets tore through the boats, throwing all into confusion. A midshipman, in the pinnace which was towing the boats, a little chap of 14 yelled, “Get ashore, men, and get at them“.

Those that were able sprang into the water, helter-skelter, pell-mell out of the boats. The water was up to our necks, but stumbling and wading we reached the shore and rushed for any bit of cover that was available.

The first man ashore on the peninsula was Lieutenant Chapman of the 9th, followed by Colonel Lee, Major Robertson, Major Salisbury, Captain Ryder, Dr Butler and the men of the leading boat. Packs were thrown off and bayonets fixed. All this time a machine gun on the cliff above us had been pouring a hail of bullets into the landing party.

Dr Butler had lost some of his stretcher-bearers in that deadly fire and this made him very angry.

“Come on men; we must take that gun,“ he cried, and started climbing the cliff, his revolver in his hand. We stormed up the cliff behind him. Sergeant Flowles and Patrick Courtney were on either side of me as we climbed the cliff, and both were shot dead. We rushed the gun and bayoneted the Turks who formed the gun crew. Smashing the gun so that it could not be again used we dashed forward to storm the next trench, the line growing stronger as the boys rushed up to reinforce. On and on we went right up the cliff to the summit, where we had to pause for sheer want of breath. Looking below, we saw the British ships shelling the Turkish positions, while the Turks replied by shrapnel over the landing place. Boat after boat was smashed under our eyes and the occupants mangled or drowned.

The sight maddened up. “On Queenslanders,“ came the cry and with bayonets fixed we rushed for the Turkish position. Then we saw the enemy coming up in force. Taking advantage of every bit of cover available, we emptied our magazines into them again and again. The Turks fell like leaves, but still more came on. The order came to retire. Bullets flicked all around us, many of the boys fell and we had to leave them.

Slowly and steadily we fell back to the shelter of the captured trenches. Then the battleships began to open out on the advancing Turkish hordes. The Queen Elizabeth, Triumph, London, Canopus Swiftsure, Majestic, a Russian battleship and a number of destroyers poured an avalanche of shell and the Turks crumpled up.

All that day and all through the night the awful din continued. Water was scarce, wounded and dying men were all around us, and our rifle-barrels grew red-hot from the continuous firing. On the Tuesday afternoon the enemy renewed the attack with vigour and things looked very black for us. We had been without sleep for nearly 60 hours and the water was all gone. We felt that the end was near and many of us shook hands as we thought for the last time. There was no work of retiring, we were resolved to die where we stood.

Fate was on our side; the Turks faltered and then fell back. Had they but known what a thin line held the trenches it would have been goodbye for all of us. On Wednesday we managed to remove some of the wounded to the beach but it was risky work for the stretcher-bearers and many of the Army Medical Corps fell beside their stretchers as they tried to cross the beach towards the hospital ship.

In the afternoon word came that the Australians were to be relieved, and never was a message more welcome. About two o’clock on Thursday morning a large force of British marines took our places. Staggering with weariness, some crawling on hands and knees, others unable to move without the assistance of comrades, we reached the beach threw ourselves down and slept for hours.

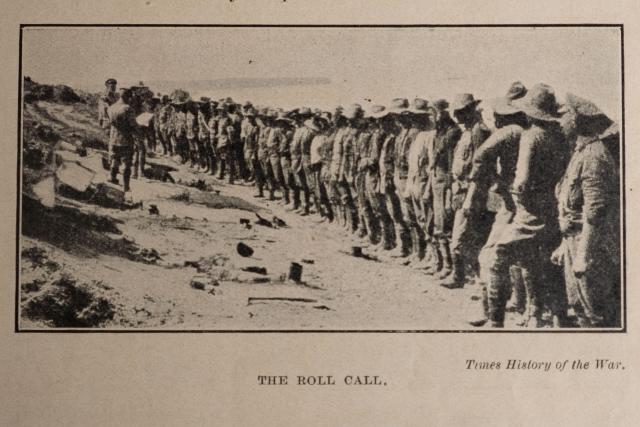

On Friday we had a muster and roll call. The diminished numbers of the 9th were enough to sadden the stoutest hears. There were but some 420 officers and men effective out of our battalion of 1100.