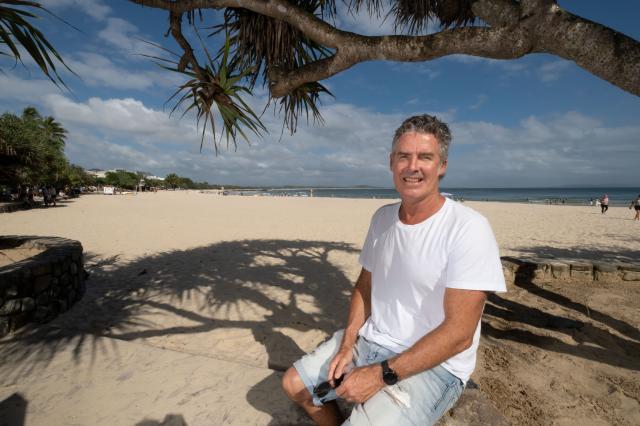

He’s been The Coach for so long you tend to forget that affable Darren Mercer was once a superstar of Australian sport, charging out of the surf on your TV screen, bodysurfing across the front of a box of Nutri-Grain.

“I used to go down the cereal aisle at the supermarket, turning the boxes around so everyone could see my picture,” Darren joked to the cameras when he and fellow ironman champ Trevor Hendy passed the cereal box baton to their superstar children, Jordan and TJ, in 2020.

Darren’s little gag is particularly funny if you know the bloke, because that’s so not him.

In 2020 the Nutri-Grain brand was celebrating a hugely successful 40-year association with surfing, surf life saving and, specifically, ironman. When the cereal company started sponsoring the extreme end of the surf club sports in 1980, ironman started to develop a profile, but when Aussie filmmakers decided to fictionalise the rivalries and parental pressures and create a real event as its centerpiece, ironman exploded onto the public radar.

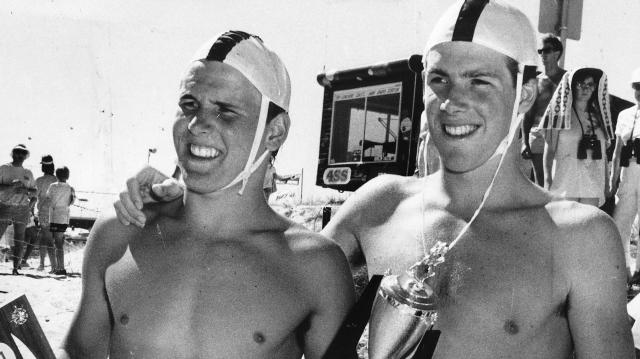

I was on the beach covering for a national magazine when a young Guy Leech won the first Coolangatta Gold in 1984 and the excitement was electric. This was a surf carnival like we’d never seen before, packed with action and passion. Darren Mercer and his brother Dean, two years younger, made their debuts in the Gold a couple of years later, and by the start of the ‘90s, the Gold and the ironman national title became battlegrounds between Wollongong’s Mercer brothers and the Gold Coast’s Trevor Hendy.

“Yep, we grew up in the Trevor-era,” says Darren, just back from a family Christmas at Thirroul, which is not quite Wollongong but a full-blooded surf town just to its north.

He remembers getting quite a ribbing from his hometown mates when ironman’s push into commercial territory saw him everywhere, particularly when Nutri-Grain produced a TV commercial starring a very young Darren and the immortal voice-over line, “Watch the boy become the man”.

“Look,” says Darren, “We were just in the right place in the right time, we just sort of fell into it. I think Trevor (Hendy) liked it more than we did, but you get used to it, and being a media face wasn’t as invasive as it is now. And I can tell you, we didn’t have the media savvy of kids today.”

When Darren talks about his illustrious ironman career it is invariably we rather than me, and the we is younger brother Dean, with whom he trained and against whom he often competed, two sides of the triangle they formed with Hendy. The brothers were inseparable rivals and friends, and the great tragedy of Darren’s life was to lose him to a heart attack at just 47 in 2017. When Darren eased up as the years wore on, Dean remained pedal to the metal, taking on competitors in the surf half his age, the Kelly Slater of ironman. In the end it was too much.

But back in the day it was Darren who led the way, taking out the Coolangatta Gold in 1991, then winning back-to-back national ironman titles in 1996 and ’97, still a SLSA first.

As the new century dawned, Darren and wife Tiana had two young daughters, Jordan and Madison, and a life after ironman to consider. They chose the Sunshine Coast, buying on Minyama Waters while Darren worked in coaching for Mooloolaba surf club.

Says Darren: “Actually, we were looking to come up to Noosa quite early in the piece because (Noosa Tri founder) Garth Prowd had taken me under his wing, but at that stage there was no ironman training facility in Noosa so we went first to the southern end. Wish we had come straight here! A lot of the ironman guys, like Barry Newman and Leechy, came north to Noosa to train with Alan Coates, but Dean and I were happy with our home environment too. But as I got towards the end of my career with a young family, we just did it. There was no real issue at Mooloolaba, but when the coaching position at Noosa came available (in 2010) we jumped on it, because this was really where we wanted to live. And we love it!”

Darren says first-born Jordan started doing gymnastics with her mother and proved such a natural talent that she was offered an opportunity with the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra. Says Darren: “We actually thought about moving back south, but we didn’t want to, and she’d also fallen in love with Nippers, so we decided to stay. And guess what? Her talents in the ocean began to blossom.”

That’s kind of an understatement. Jordan Mercer went on to become a record-breaking ironwoman and endurance ocean paddler, whose frantic career is only now being balanced by demands of study and marriage.

Says Darren: “The decision to start winding down is all hers. We’ve never forced or pushed her to do anything in sport, it had to be her passion, and it is. And she started winning so many titles. A couple of injuries set her back quite a lot, and she was determined to finish university so that got in the way a bit too, but she’s almost finished now and mid year she’ll be a teacher, which we’re very proud of.”

I ask the Noosa Surf Club head coach to describe his routine.

“A lot of people think you just rock up and do a bit of coaching and go home, but there’s always stuff behind the scenes that needs to be done. My role is admin as well as coaching, working out the events’ schedule and the travel. There’s also a lot of personal connection with parents as well as the athletes, who I work with from Nippers to Masters. The role has broadened my skills a lot, and I love it. And if I can pass my skills and my experience onto the next generation, I love that too.”

One last thing. I tell Darren I’ve found a classic picture of him celebrating his 21st birthday with his surf club buddies, and it reveals his birthday falls on the day this paper is published.

“Wait, what?”

He sounds puzzled.

“Oh, I know. The picture’s from January, right? We always used to race and train right through December, so I couldn’t celebrate my 12 December birthday. We’d have a fake one in mid-January.”

So there you have it. The coach is 54 and one month old today. Doesn’t look it.