A cool wind ripped through the cabin just before dawn, slamming doors and making the corrugated iron shudder.

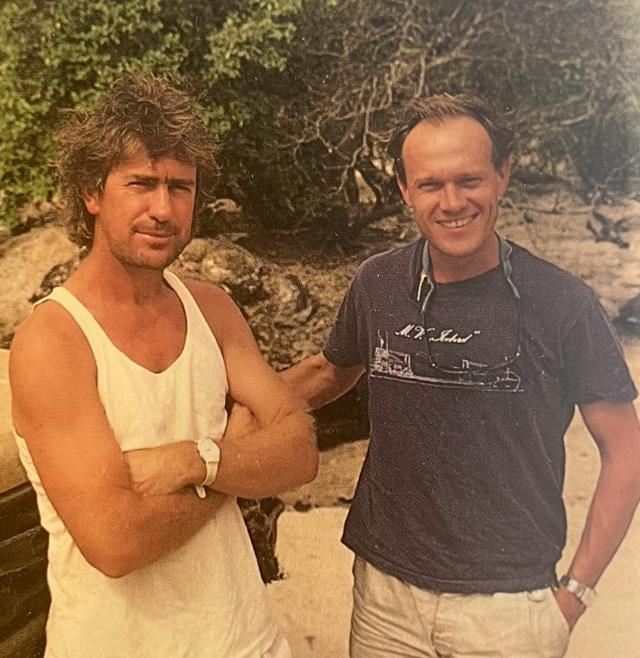

Photographer Paul Wright and I were awake and out of our bunks instantly. Outside on the red sand, still warm from the heat of the previous day, we scanned the horizon for signs. To the east, where the grey of predawn was turning pale yellow, we saw nothing but the shimmering surface of the Gulf of Carpentaria. But to the south, coming in off the Australian mainland 40 kilometres away, a carpet roll of thick cloud extended in a band across the horizon. The Morning Glory was on its way.

The Morning Glory roll clouds which appear over the south-eastern part of the Gulf each spring are neither widely-known nor fully understood, beyond meteorologists and the band of glider pilots who travel from far and wide to ride the cloud-wave. Similar roll cloud formations are seen in other parts of the world, but none with the regularity and intensity of those of the Gulf. I had seen part of one previously, from the heavily-wooded bank of Gin Arm Creek near Burketown, and wondered what all the fuss was about. As the sun rose on Sweers Island I was about to find out.

Wright and I ran out to the bluff to get the best vantage point. Later, the temperature would nudge 40 degrees, but we stood shivering as the breeze ushered in the Morning Glory. The sky was becoming a faint blue as the cloud rolled towards us, but at its most dramatic point it turned a foreboding black as the cloud passed above us and rolled out across Investigator Road towards the top of Bentinck Island. It was one of the most amazing shows of nature I had seen, and remains so 35 years later, but in terms of amazement, Sweers and Bentinck were only getting started.

With Tex Battle now in his 80s, Sweers Island Resort recently changed hands for around $4 million, which included, on top of the leasehold, six plush cabins sleeping around 30 guests at capacity, two houses for management and staff, eight hire boats and a six-metre cat, sheds, workshops and an aircraft hangar, mobile phone reception and satellite internet. When I first visited it had a radiophone hookup to the Flying Doctor and a CB link to the main camp on Bentinck. As I wrote back then: “It is impossible to think of a less accessible tourist facility – four hours from Cairns to Burketown on the Flightwest milk run, then another 20 minutes on a charter plane.”

And it wasn’t very pretty either, at least not at first. I wrote: “It takes time to see and feel the elemental beauty of the South Wellesley Islands, time to watch the primary colours of the morning bleach into an outback noon and then gather force for a blazing sunset. And it takes time to be drawn into the fascinating history of this part of the Gulf, its tales of bravery and stupidity, magic and cruelty.”

In his excellent book Killing For Country, referenced in the first part of this story last week, author David Marr’s interest in the twin islands of Sweers and Bentinck understandably waned when his forebear D’arcy Uhr moved on, but the killing of the Kaiadilt people continued sporadically, well into the new century when a man named McKenzie lived amongst them and is estimated to have slaughtered 11 people and raped numerous young girls. Unfortunately, as I learned firsthand on my first visit in 1989, the trials and tribulations of the Kaiadilt did not end with McKenzie’s departure.

Between the world wars Presbyterian missionaries established an outpost on Mornington Island to save the souls of savages and “bring them in” from the island camps. They soon had a flock but the Kaiadilts managed to avoid such indignity until in 1940 an intra-tribal fight resulted in 11 of them being jailed on Cape York after the murder of a Mornington Islander. A RAAF radar station was established on Mornington soon after and in 1943 a party of airmen made a boat landing at Sweers where the Kaiadilts had set up a fish dam. Alarmed by the approach of the airmen, they threw spears and in the ensuing battle a young Kaiadilt man was killed and a woman wounded. This was the last officially recognised battle between blacks and whites in Australia, but it was also the last hurrah for the Kaiadilts on their Bentinck homeland for more than a generation. Slowly they were “brought in” to the mission on Mornington, with the last of them being expatriated when a tidal surge in the Gulf left the small Bentinck population without fresh water.

In October 1989 I was cleaning my morning catch of queenfish on the beach at Sweers by a pile of rocks – possibly the remnants of the 1943 fish dam – when a tinnie full of Kaiadilt men pulled into the shallows and were led up the beach by a middle-aged white man sporting tribal tattoos and dirty camouflage pants. Later he introduced himself as Selwyn Hausman, a former Sydney barrister who had married a Kaiadilt woman and in 1986 had begun the long process of setting up camps on Bentinck to repatriate them.

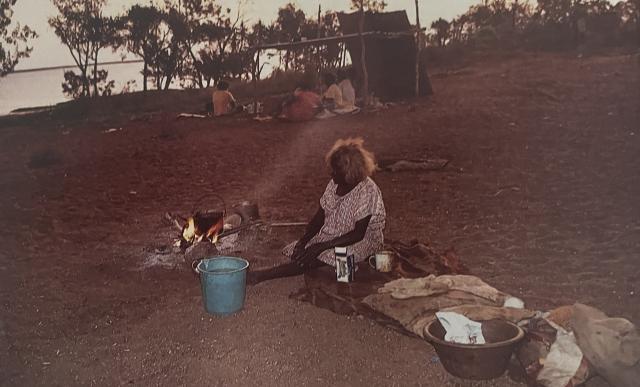

Hausman invited me to join his men on a turtle hunt that afternoon and to sit and chat with the families on the beach later on. Although our hunt was futile, I was pleased to find a drum of turtle meat heating on a bed of coals when we reached the circle of people spread out on the beach in the late afternoon. I’d been hunting with a man called Billy Dundaman, whose wife, Alison, proved to be a font of knowledge gleaned from the old stories and her own lived history. She told me that when she was a little girl her mother, Roonga, was shot in the leg by a white man in uniform on the beach at Sweers. I did a quick age calculation of the middle-aged woman sitting beside me in the sand and my skin went to goose bumps as I realised that Roonga had been shot by the RAAF raiders in the last black/white battle 46 years earlier. “I don’t bear no grudge,” Alison told me. “Both sides wrong that day.”

When we visited Sweers and Bentinck in 1989, Tex and Lyn Battle had only been running the resort a little over the year, while the Kaiadilt homelands program across the strait was at a very early stage with just a couple of small camps established. By 1991 it was a different story. Bentinck had three established dry camps with a permanent population of around 30 people from three generations, a well, a generator (usually on the blink), a market garden and several fish dams, but while the Kaiadilts had re-established their traditional lifestyle, they were still dependent on Sweers for some supplies, including occasional fresh water, and their mail.

To make transactions and inter-island communications easier, Lyn Battle (a writer of romantic novels in an earlier life) had started to compile a Kaiadilt-English phonetic dictionary, enabling the women to shop for supplies using their own tongue. She cradled the little book on her lap when we took the tinnie across Investigator Road for an official reunion with the Kaiadilts.

Although the meeting had been organised over the CB radio, I was still struck by its formality, with Kaiadilt People’s Corporation chairman Roland Moodoonuthi and Billy Dundaman, my hunting buddy from ’89, wading into the shallows in their Sunday best to greet us. Other men crowded around as we walked up the sand, while the women and children sat shyly in the shade of the palms. But the mood changed abruptly when a woman called Dawn emerged from the scrub and performed a wind dance on the sand. Within moments a gust of wind roared across the beach as the group erupted into cheers and laughter.

The fuss drew Roma Kelly, mother of the chairman and the oldest living Kaiadilt, from her solitary campfire and grass bag production line. She sat down beside me and went through a repertoire of bird calls before telling me, with some help from Lyn Battle and her dictionary, the chilling stories passed on by her parents as eyewitness accounts of murderer John McKenzie’s reign of terror in the early 1900s. For the second time on Bentinck, I felt a real connection with the tragic past.

When the sun got lower and Investigator Road started to turn gold, Paul Wright and I went back to Sweers for our swags to spend the night camped with the Kaiadilts. We ate big chunks of rock cod pulled off the frame with our fingers and washed it down with warm soft drink, before spreading our swags on the sand and lying in the moonlight with our Kaiadilt mates, giggling at the existential absurdity of the space junk that threaded its way through the constellations, unaware of what really lay below.

Parts of this article originally appeared in the Australia Day edition of The Bulletin, 28 January 1992.

![[READER COMPETITION] – Win tickets to the Queensland Ballet at The J Theatre](https://noosatoday.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Queensland-Ballet-100x70.png)