The village had changed, of course, but I still had tears in my eyes as we drove through the centre of the Cantabrian town of Ampuero, where my best mate and I ran through the streets with a large herd of vicious bulls bringing up our rear (literally) almost exactly 50 years ago.

It was 1973 and we had come to Franco’s Spain, like many young writers and adventurers of our generation, fuelled by Ernest Hemingway’s glorification of the bullfighting culture over several decades, and by James Michener’s brilliant exploration of Iberia in both travel books and fiction. It’s fun to be led around the world by good books, but our mission to Spain, hitching rides and living on a shoestring, was ridiculously romantic and hysterically misinformed.

We missed the greatest running of the bulls at the Festival of St Fermin in Pamplona by two months, for example, and only found about Ampuero quite by accident. On the way there we accidentally pitched our pup tent on a private golf course, and were woken in the middle of the night by the Guardia Civil, who moved us on by shining torchlights on us and yelling while we shook in terror at the silhouettes of their machine guns outside the thin walls of the tent.

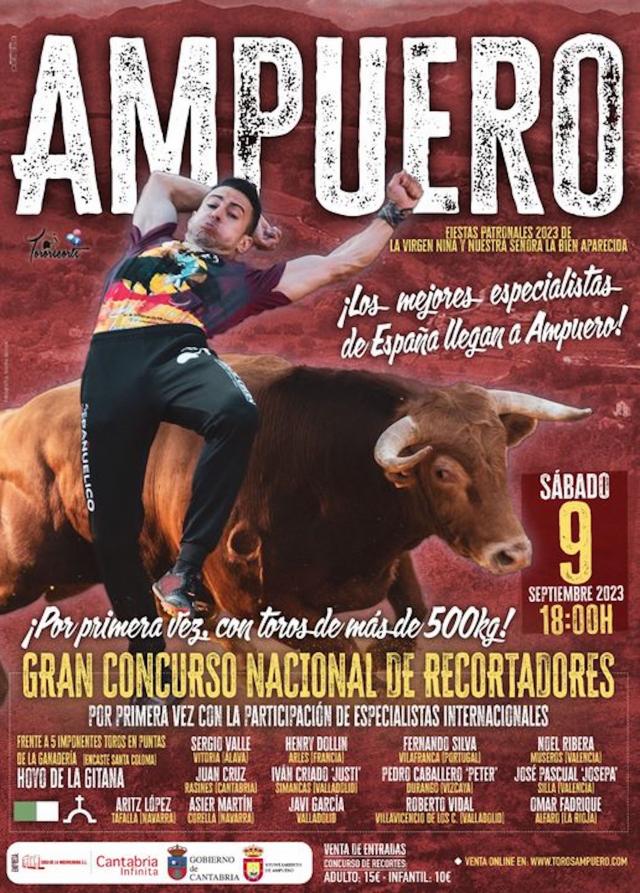

But we got to the beaches of Santander, where a young Spanish man who had attended university in Australia told us about the Fiestas Patronales of the Virgen Niña in the hillside village of Ampuero, about an hour away, held in the first week of September each year since 1941, and starting tomorrow! We couldn’t believe our luck.

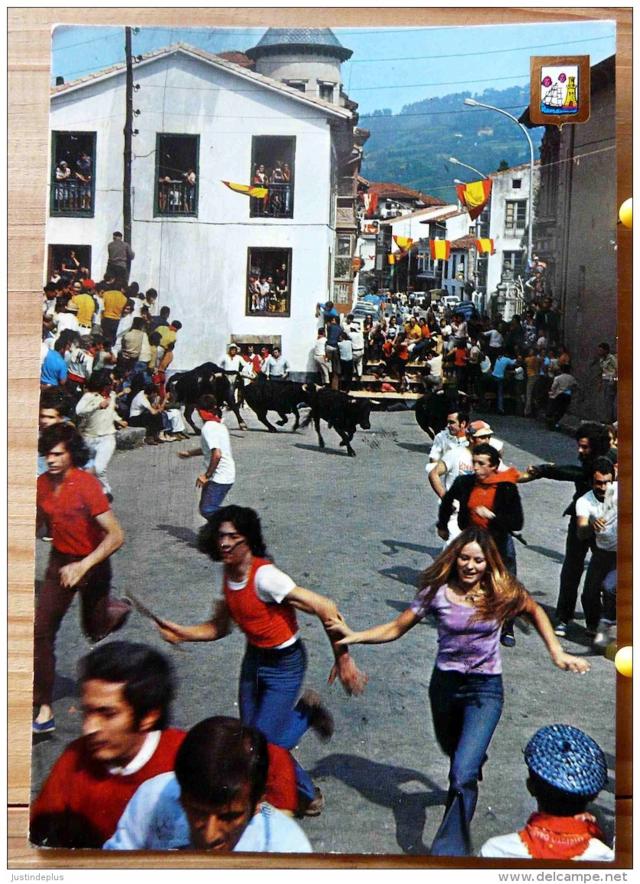

We slept on the beach and in the morning our Spanish friend returned with a ute and we piled into the back with some American students we had befriended. As we climbed into the hills we caught glimpses of ancient and crumbling stone farmhouses but the village itself, then of fewer than 1000 people, was bedecked with streamers and posters, with various flags hanging from the balconies along the barricaded main street, from which the residents would soon watch the first of three runnings of the bulls. As the morning rolled on, the streets filled with excited people of all ages, many carrying a rolled-up newspaper, to either frighten away or taunt the bull, we weren’t sure.

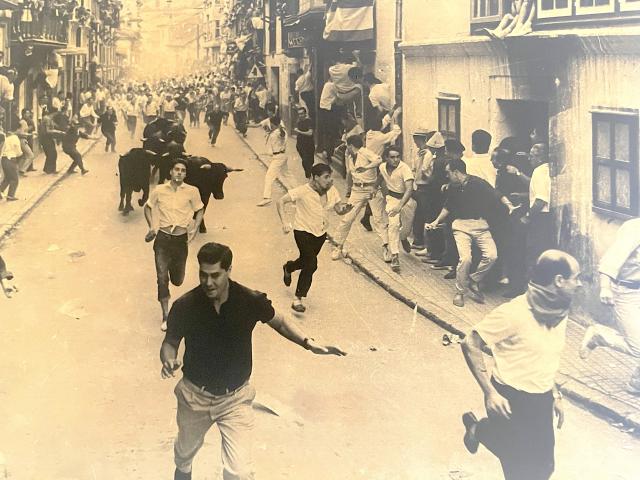

We followed the throng to the top of town where the bulls were to be released after a rocket signalled the start. A few minutes past midday we heard the rocket. For a moment I remember being unsure what to do, then the realities of the situation kicked in. People closer to the release point were now running towards us and shouting at the top of their lungs. Then the first of the bulls were visible behind them. We took off. The running only lasts a matter of minutes – somewhere between five and 10 – but so much happens that it seems like a lifetime.

At some point the bulls were among us. I remember grabbing at the barricade to hoist myself above horn height, only to be pushed back down by elderly women on the other side. I had lost my buddy, Jamo, but I managed to regroup quickly, wait for a break in the bulls and duck and weave towards the bull ring where they would be herded away from us. Hopefully.

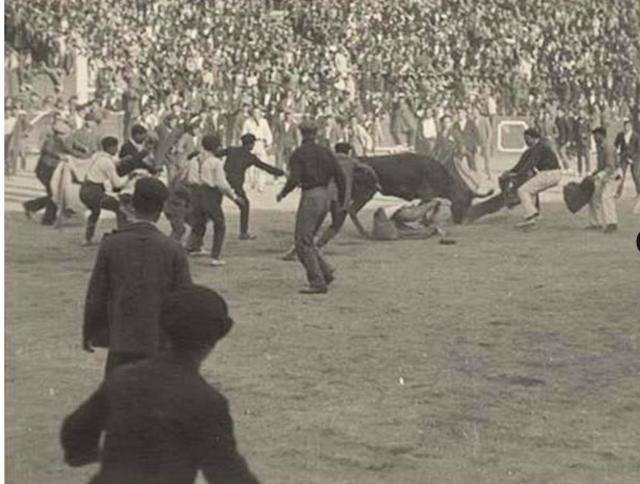

We were all reunited in the ring, no one hurt, although a couple of us had close scrapes. As far as I can recall, no bull touched me, although a few came close. But we had run, we had experienced the culture established in the 16th century. The excitement and relief was palpable. We moved from bar to bar, drinking, singing and eating handfuls of tapas with the locals all afternoon and well into the night, sleeping with our plastic wine bottles in a paddock at the edge of town.

We were told that there was really little to fear because the bulls used were mostly young and even-tempered, but in 2004 two Spanish men were gored to death and 11 others suffered serious injuries, when the bulls turned back on the runners behind them. The worst tragedy in the fiesta’s history, it caused that year’s event to be stopped. But the runners came back the following year.

In Michener’s novel The Drifters (1971), one of our guide books in ’73, the main characters who find adventure from Pamplona to Torremolinos were young students or graduates just like we were, but the narrator was the older and supposedly wiser businessman George Fairbanks. While I might have fancied myself as Joe or Cato in 1973, revisiting Ampuero for the first time 50 years later I was most definitely George Fairbanks. Although in some ways he was their mentor, George learned many things from his young friends, and I learned many things from the young me I recalled as I walked the streets of Ampuero last week.

In the intervening years I have been to the Festival of San Fermin in Pamplona on perhaps half a dozen occasions, I have watched bullfights in a mix of wonder and regret, but always excitement, but I have never come to terms with the morality of slaughtering the bull.

The barricades were up all over Ampuero last week as we took our coffee in the town square, so I video-called my mate Jamo and walked him around the streets and lanes, sharing stories of our escapades of so long ago. Then we drove out of town, not needing to see more.

Later I flipped through Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1926), in which he has one central character saying: “I can’t stand it to think my life is going so fast and I’m not really living it. Nobody ever lives their life all the way up except bullfighters.”

It’s a very good book, but sorry Ernie, I have to say yeah, nah!