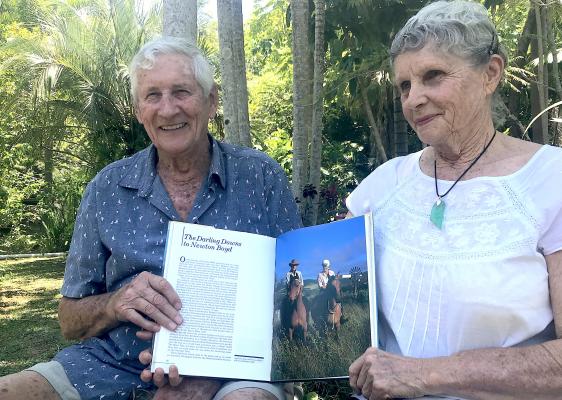

Phil Jarratt reunites with a true blue bushman

The little I know of the craft and lore of the Australian bush, I learnt from a Kiwi, of all people.

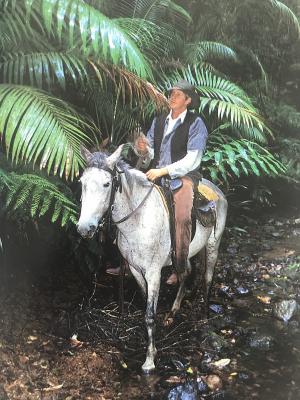

More than 30 years ago I wrote: “On a clear and lovely morning I rode east from Hodgson Vale with Bicentennial National Trail co-ordinator Brian Taylor and his wife Carene. We rode past the polo club recently built on R.M. Williams’ property, then high into the hills on a bridle path and along a plateau. From here we could track the progress of the National Trail across the fertile Darling Downs to the border ranges and on into New South Wales.

“From our vantage point we could see a long, long way, but only a minute fraction of what was to come as the Trail made its way down the Divide through two more states. Already we had spent the better part of four months exploring the trail through Queensland, and at times we were road-weary. But it wasn’t our homes in the city we yearned for – it was the time to do the country justice.”

I still feel that way when I go bush, like I need more time to follow that creek bed around its bend, talk more to that character in the pub, to lie on a swag at night and watch the constellations, to listen for birdsong at dawn. Along with travelling saddle bag lite, making a chunk of salted beef last a week, getting a horse down a boggy zigzag and a hundred uses for a forky stick, Brian Taylor taught me what to look and listen for in the bush, and how to appreciate its flora, fauna and people.

During the latter half of 1987, and into the Bicentennial year of 1988, with photographer Jan Subiaco, we explored the more remote parts of the 5,300-kilometre National Trail from Cooktown to Healesville near Melbourne on foot, by 4WD and, wherever possible, on horseback. Along the way Brian introduced us to an incredible cast of characters, from bush poet Bob Harlow – who would crouch by the campfire and watch the horses all night, while rolling endless Tally Hos and reciting in his mellifluous voice, “I was born upon the Daintree, I’m a product of the land … ” – to the legendary R.M. Williams, Brian’s mentor, whose idea this incredible trail was.

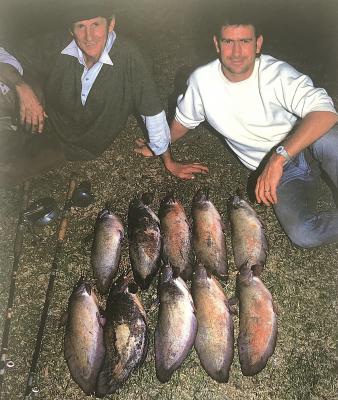

Brian Taylor’s friends became my friends through a bond of trust you only find in the bush. When I wrote a book about our long trail ride, old Reg Williams contributed a heartfelt and generous foreword. When Bob Harlow’s wonderful Aboriginal wife Viv died prematurely – “Dunno what’s gonna get me first,” she’d say, “too much salt or too much of Bob’s BS” – I flew up to Mossman at the family’s request to deliver a eulogy.

And yet, somehow the years flew by, and even though in retirement the Taylors had moved a decade ago to the furthest reaches of Noosa Shire to be closer to family, we hadn’t seen each other for 30 years until last weekend, when I drove up a steep hill to a comfortable home surrounded by forest, and watched Brian, the bloke who once rode tall in the saddle as TV’s “Carlton Drover” (Australia’s equivalent to the Marlboro Man), hobble out on his bionic ankles to greet me.

Now in their eighties, the Taylors are selling up and moving into town after a lifetime on the land, but it’s a wrench. While Carene showed my wife over their beautiful gardens, Brian pointed out a wild peacock and showed me the breaks in the thicket where the ‘roos come in at dusk. “Never seen a dingo here, but I hear a few,” he said.

The stables on the property are empty now. Brian’s artificial ankles and replacement hips – the result of tough first grade rugby in New Zealand, a bad car accident and decades getting in and out of the saddle – haven’t allowed him to ride for years, but Carene, an equestrian rider and horse-breaker of note, only hung up her riding boots this year. Still, being so close to the elements of a lifelong passion for the bush is something they know they can’t replace.

Brian first returned to the land of his father’s birth in the 1950s, and worked the big cattle runs of Queensland before returning to New Zealand to gain an agricultural degree. Later, he and fellow Kiwi Carene married and settled on the Atherton Tableland to raise a family. He taught from time to time, but his heart was in the bush and he was never happier than when droving, shearing, fencing or rough-riding.

And then along came Reg Williams. The legendary stockman who founded a saddlery in South Australia in 1934 and later branched into boots, was a multi-millionaire long before he met Brian while researching his concept of a horse trail to follow the Great Divide from one end of Australia to the other. In the younger man he found a kindred spirit, which happens to be the name of the Taylors’ hinterland property.

Says Brian: “Reg had a lot of money but he never forgot where he came from and he treasured the idea that kids were our future and that they could learn so much from experiencing a trail that took them into the heart of our country, like the Americans had with the Appalachian and Redwood trails. Reg also had this thing about kids from the bush having equal opportunity for education, so he said, you’re going to come to Toowoomba where they can have both, and you’re going to work for me.”

Soon Brian was working in a little office on R.M. Williams’ two pet projects – the Stockman’s Hall of Fame and the National Trail. While he contributed to both, his work on marking and mapping the trail, securing access from both Europeans and First Nations occupants, and writing the history of the areas it crossed began to occupy all his time. By the mid-‘80s, both he and Reg realized they were going to need help to finish the project, and it came in the form of the now-controversial Bicentennial of European settlement.

Although Bicentennial funding would later mean widening the trail concept to include bikes and even 4WD vehicles on some sections, when I met Brian in early 1987 while he was negotiating access through the Widden Valley west of Newcastle, all of that was for the future. I loved his passion for the project and we struck up a friendship that within months had turned into an adventure of a lifetime. For me at least.

Until we left China Camp and headed up Gold Hill for our drop down onto the Daintree River, I didn’t tell him that I’d had my first riding lesson two weeks earlier. After a week of saddle sores and a couple of nasty drops into the mud, he’d probably figured it out.

After the opening of the Bicentennial National Trail in 1988, Brian told Reg he couldn’t stand office work for a moment longer and had to go droving. Says Brian: “I’m out Barcaldine somewhere a month or two later with 8000 wethers, and one morning there’s this cloud of dust and a big LTD Ford pulls up and Reg Williams climbs out. I said, do you want a drink of tea, old fella? He said, ‘I just had to come and see how you’re going.’ We had a wonderful friendship.”

Reg Williams died in 2003 and a few years later the Taylors shifted camp to Noosa Shire to be nearer children and grandchildren. (In fact, we found out last weekend, we have grandsons in the same soccer team.)

Over the past few decades Brian has published five well-received books of short stories and verse celebrating the bush, starting with The Forky Stick in 1988, which he proudly gave me on our last trail ride together. It was a long time coming, but earlier this year he was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM) for a lifetime of services “to rural and remote communities, and as an author”.

As we got up to leave after a memorable lunch, I asked the great storyteller what he’d do when they moved to “town”. He said: “I often think about that, and I reckon I could go to old people’s homes and read stories, share the wonderful life I’ve enjoyed in the bush. I’d like that.”

He leaned in as he adjusted his ankles for the stairs and whispered: “And I’d like to see them rename the National Trail the ‘R.M. Track’. Make sure you mention that.”