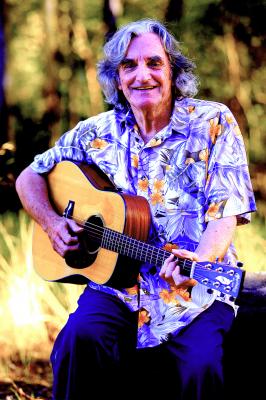

The senior gent with long hair dangling from under his floppy hat finishes his light beer, excuses himself from the table and rises uncertainly with the help of walking sticks to make a slow progress, his baggy trackie dacks flapping in the breeze, across the restaurant to the bandstand, where he eases into a chair, picks up a guitar and strums a quick warm-up.

Yes, the dude is in his golden years, no mistaking that, but the moment he adjusts the mic and leans in to allow that rich five-octave range to fill the room, he loses 20 years, maybe more, and he is unmistakably Barry Charles.

In case you just got here or you’ve been under a rock for the past 40 years, Barry Charles is a rock god in Noosa. He’s the leader of the tribe, mentor to many, the muso cruising around naked on the outer bays, the man with the golden tonsils, the guy who put the country into soul and soul into our part of the country. He’s a man who loves life with a passion and his passion for making beautiful music has been bringing love and light into the lives of local audiences for almost half a century.

And for all but the first of his 72 years, Barry has lived with the spectre of poliomyelitis and its sinister cousin, post-polio syndrome, which can come back and hit you even harder than the first time. That’s what Barry’s living through right now, and his response is to work even harder, play more gigs, spread the love, cover the South-East from Hervey Bay to the border, wife of 35 years Diana Dummett at the wheel, helping lug the gear, helping Barry avoid the unthinkable, which is no longer doing the thing that has blessed his life.

Barry Charles was just 15 months old when he was diagnosed with polio as yet another epidemic of this life-threatening and crippling disease attacked a new generation of Australian children. Within a handful of years the availability of the Salk vaccine would virtually eliminate the virus, but if you went to school in Australia in the 1950s, you will remember that virtually every grade had an unfortunate kid with skinny, misshapen limbs. More than 400,000 Australians, mostly children, were affected by polio in the 1950s.

Barry is not given to righteous indignation, but his lip begins to quiver just a little when today’s anti-vaccers are mentioned. He takes a moment to settle, then says quietly: “I can’t understand how any parent could deny a child a potentially life-saving vaccine.”

The Charles family lived on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula and Barry’s dad ran the family shoe factory in Collingwood, so Barry, still in nappies, was sent to the Yooralla Hospital for Crippled Children, where an astute doctor told them that the best polio treatments in the country were at the Montrose Home for Crippled Children at Oxley in Brisbane. There was no option: the family moved to Queensland, and lived at various points around the South-East while Barry began a series of treatments, seeing his Mum and Dad once every two or three weeks. He was to spend more than four years at Montrose.

He recalls: “It was terribly lonely for one so young, and I think that kind of loneliness stays with you. I get upset even now when friends don’t come to see me. Before vaccinations the main way of dealing with polio was they’d just try to straighten your bones. They had very strange ways of dealing with it. They’d put you in a frame and tie you down. Of course, even at that age, I understood that the doctors were trying to make me better, but it was tough.”

And Montrose set him on the road to recovery, coupled with several later operations that allowed him regain sufficient use of his limbs to enjoy an almost-normal later childhood, with a few caveats. Back in Melbourne, he yearned to play football, but was banned after his remaining caliper injured another player. His response was to form a ukulele duo with an asthmatic schoolfriend who was also sports-deprived. When she heard him sing, Barry’s mum immediately booked him in for lessons. But she shouldn’t have been surprised – it was in the blood.

Barry says: “My grandfather was a great opera singer who sang with Dame Nellie Melba in Melbourne Town Hall in 1927. He was still singing Jerusalem to me in his 80s, when he was quite ill. It moved me to tears. Dad was a good dancer who could sing too, he liked Mario Lanza stuff. Years later I had a music teacher in Brisbane and he told me I should be doing live opera. I said, no, I prefer Joe Cocker and Tom Waits.” Performing music gave him a self esteem that was new and exciting, and by the start of the 1970s he was ensconced in the vibrant music scene of Prahran, driving a Silver Top taxi by day and playing and singing with a band called Winchester by night. Another of the band members, Andy Tainsh, told Barry his parents had relocated to a place called Lake Weyba, near Noosa, he was thinking about taking a trip up there and maybe Barry would like to come along.

Barry recalls: “I probably would have let the invitation slide, because the Prahran scene was an education for me, the music, the drugs, the whole thing. But I got into some pretty crazy relationships, and one was with a woman who was a clairvoyant, and she said, ‘This relationship is going to stop soon because you’re going on a big trip.’ I’d just bought an old Zephyr, the only thing I couldn’t leave behind was my dog, so I thought why not, and I followed Andy north.”

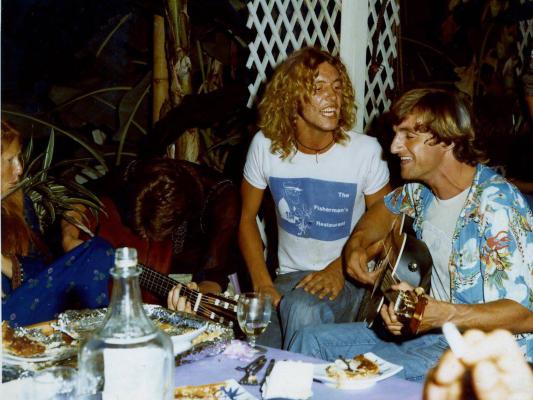

Although their Eumarella property was basically a collection of sheds, Doug and Alice Tainsh had turned it into a thriving salon of artists, writers and environmental warriors. Barry was basically adopted by the family and did odd jobs around the property, including making mud bricks for the new structures going up. Every day he met the leading lights of Noosa’s cultural community, like artists Hal Barton and Emma Freeman, and writer Nancy Cato. A highly respected cartoonist and TV scriptwriter in his Melbourne career, Doug Tainsh became a second father to Barry, who had recently lost both his parents.

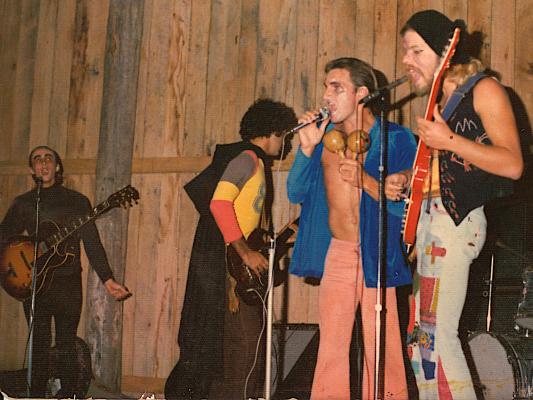

Meanwhile, the boys played rock and roll. Barry and Andy formed a duo to play small gigs at all the cafes and bars that were springing up all over Noosa, like Doddies, Dooley’s, the Reef Hotel, the Royal Mail, the Green Cherry, Barry’s On The Beach and the Noosa surf club. They got so busy that Barry moved into a tent at The Woods caravan park so he could walk from gig to gig. But they soon missed the camaraderie and the sheer noise of a band, and Barry and the Rockets was formed.

Initially the rhythm section was made up of local surfers who could play a bit, but when a good swell took precedence over rehearsals, Barry called in experienced Melbourne musos Gavan Anderson, Rick Matson, David Allardice and Colin de Luca. And the Rockets took off! Soon they were playing the length and breadth of the Sunshine Coast and beyond, prompting Barry to invest in an old caravan he could tow to Caloundra or Belli and save the long drive home.

The Rockets had a light show, wore hippie beach garb and jumped around a lot on stage. Their set lists combined Joe Cocker, the Animals, Sam and Dave and Eagles covers with their own quirky originals, often extolling the virtues of the Noosa good life, surfing naked at Granite, slurping smoothies at Harvest, picking gold-top mushies in the hills. They captured Noosa in the ‘70s perfectly, but taking the sound back to Melbourne proved to be a mistake. As Barry wrote in his 2009 booklet, You Had To Be Out There, “The Melbourne audience just wasn’t ready for our kind of hippie hop.” They played their last gig at the Station Hotel in Prahran and went their own ways.

Because many of the venues he played had licensing restrictions on amplification, Barry had taken to seeking out small country halls they could rent for a night for a pittance and turn into hippie heaven. In the mid-1980s he started doing just that, creating spectacular full moon dances at the Tinbeerwah Hall, with all of Noosa’s most “out there” musos, like Geo Heathcote, Bob E. Lees and Ewan Mackenzie on the bill and patrons told to bring “something for the copper”, which was not a bribe but a liquid contribution to the potent punch that quickly filled the huge old copper. Says Barry: “They’d bring beer too, but most people wanted to be surprised by the punch.”

Later they moved the party to the Verrierdale Hall, where Barry and Diana were married (Doug Tainsh best man) in front of the whole gang, which by now numbered several hundred for every gig. The Verrierdale Lost Lamington Shows (a nod to the lamington CWA morning teas also held there) helped raise much-needed funds for local charities and sports clubs, setting Barry on a course for the future.

There were other great bands – in the ‘80s Barry Charles and the Last Resort played all over Brisbane and toured the state, in the ‘90s a blues and soul outfit called The Big Easy allowed Barry to really exercise his vocal range – but another passion was community radio, and Barry became founding president of Noosa Community FM when it began in 1996.

By the turn of the century Barry was starting to feel the onset of post-polio syndrome, and he and Diana decided to take a big overseas adventure while he could manage the travel. For the next four years Barry played pub gigs in London and Cornwall while Diana worked in design at Virgin Records. The adventure culminated in a three-month-long beach club jam in Jamaica, where Barry played alongside British rock legends Dave Mason of Traffic and Alvin Lee of Ten Years After.

He came home exhausted but inspired to begin the next phase of his storied career, playing sit-down gigs at venues and blues and jazz festivals across Australia and New Zealand, writing and recording and focusing on how he could help disabled people find a pathway through life. He’s been committed to that cause ever since.

Meanwhile, back at Noosa Harbour Wine Bar on a Sunday afternoon, a crowd of old faithfuls has gathered to hear the master. Three bars of strumming and Barry’s good to go. He throws a shaka at wheelchair-bound drummer Wayne Carlson and launches into a stunning rendition of his own Tea Tree Bay Blues, finishing with an impossible scat that only he could do.

Still Barry after all these years.