They say you should never meet your literary heroes for fear of disappointment, and I think there’s an element of truth in that, although the fault might lay with the expectations rather than the hero.

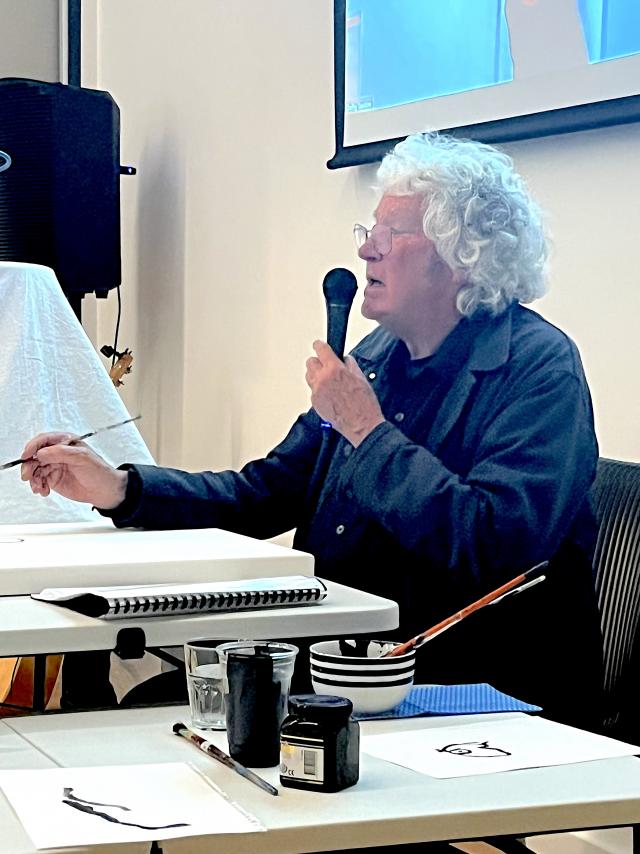

The thought came back to me the other night when, following a glowing introduction, an old man with a shock of white hair, dressed in jeans and sandals, shuffled to the microphone at the front of the room and seemed to struggle with its operation.

I use the term “old man” with the same sense of reverence used by Noel Pearson when he referred to Gough Whitlam, with the highest level of love and respect, as “this old man” in his beautiful eulogy.

Being but a few years behind him, I don’t get to call Michael Leunig old with anything other than reverence. But in a way, the great cartoonist, poet and philosopher has always seen the world through the prism of a wisdom way beyond his years, and often completely beyond our comprehension.

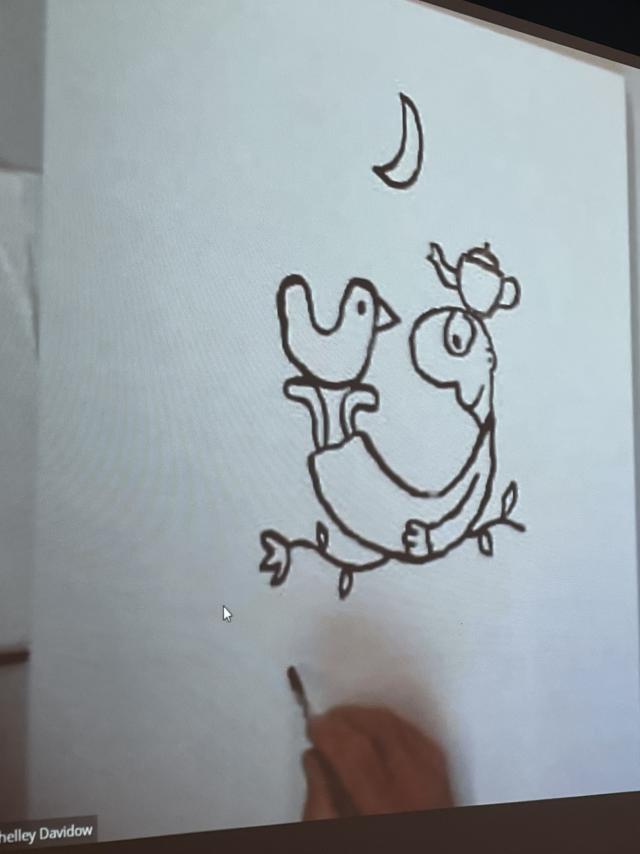

Except that it all made perfect sense, the duck, the moon, Mr Curly and Vasco Pyjama, the whole damn circus. It was the universe drawn small.

As Barry Humphries wrote in 1975: “Leunig’s subjects are as ambitious as his technique is simple. World cataclysm, The Flood, loneliness, cruelty, lust and greed. Through these runs the vein of his compassion and humanity – his humour – illuminating many a darkling theme.”

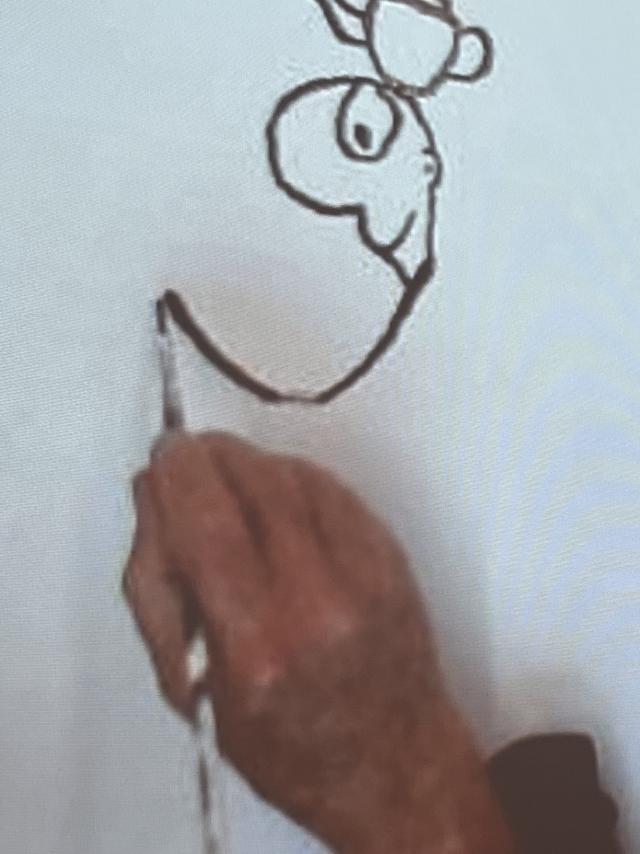

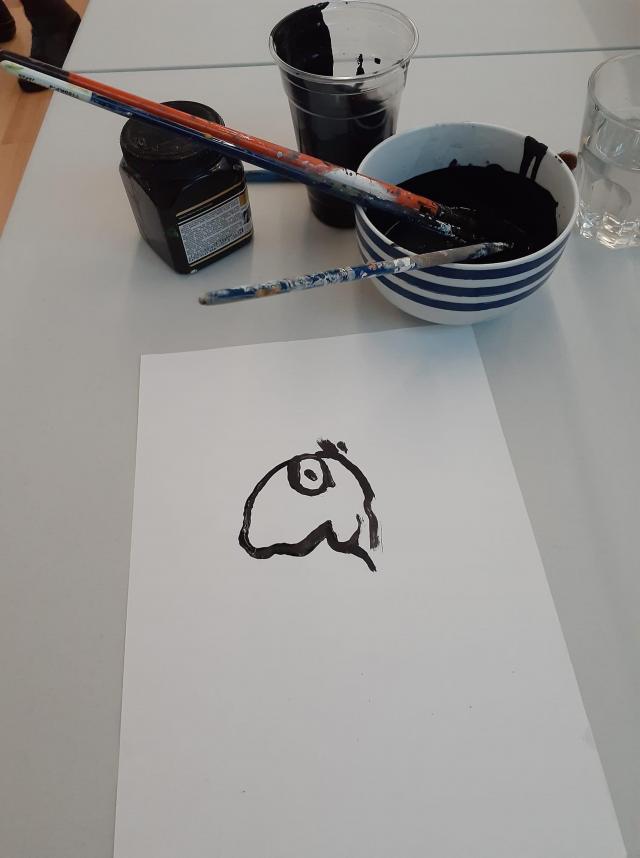

Or as the artist himself put it in 1992: “A cartoonist will create a standard figure – the Everyman, Everyperson image that becomes their messenger, their angel … In my case I create this character gradually over the years, this poor little wretched fool with big wide eyes, a bit of an innocent. He’s a bit genderless, a bit ageless — not quite human, more humanoid. A bit like a monkey or a foetus. But it’s a life spirit, you see, that people can trust. There’s no possible threat with this character. It can propose the most ridiculous things, or soft, touching little innocent things or it can be bawdy … People know it, know it can say anything and they always forgive it.”

Michael Leunig, now 77, spoke to a packed room at the Peregian Beach Community House launch of the Write On The Coast literary institute.

“I’m so grateful to you all for coming and I hope I can make it worth your while. We’ll see.

“I haven’t talked to a room of people for a long time but hopefully I’ll slip back into it. It’s been advertised as me talking to myself, but if at any time you want to proclaim something, go right ahead.”

Having immediately won the audience with the humility of his cartoon humanoid, he then launches into his introduction to our region.

“I first came in 1963 when there wasn’t quite so much here.

“I hitchhiked up with a friend, before all the development and it was so beautiful. I have great memories of travelling through Queensland with a rucksack on my back.

“There was a family connection too, because my uncle was sent as a young man to Maroochydore to do his jungle warfare training before going off to New Guinea. I was curious about Uncle Cookie’s experience here because when I was little he’d sit with me and try to give me a little glass of beer while he told his stories.

“I always remember how enjoyable those times with him were. So I feel an affinity with this area.”

It’s typical of Leunig’s body of work over more than half a century that he uses a tiny splinter of childhood memory to conjure an image that fascinates but leaves you a little puzzled as to its true meaning.

Over the long ramble that he later refers to as “my muddled talk”, he does this often, leaving a partly-formed idea suspended above us, just out of reach.

Born in East Melbourne in June 1945, he was the son of a slaughterman, the second of five children.

His website bio contends he “was educated at Footscray North Primary School and Maribyrnong High School, plus at various factory gates, street corners, kitchen tables, paddocks, rubbish tips, quarries, loopholes, puddles and abattoirs in Melbourne’s industrial western suburbs”, finding creative inspiration from “Enid Blyton, Arthur Mee, Phantom comics, The Book of Common Prayer, J.D. Salinger, Spike Milligan, Bruce Petty, Martin Sharp, Private Eye magazine and The Beatles”.

Following his dad into the meatworks straight from school, Leunig is politicised by receiving his military conscription papers in 1965.

We’re not sure how he dodged that bullet, but he finds fame – and later adulation – as a political cartoonist on the game-changing Nation Review at the start of the ‘70s.

As a casual contributor to the Review who never missed an issue, I was amused, fascinated and puzzled by Leunig’s cartoons, never having seen anything quite like them. I remain, more or less, in this state.

The list of Michael Leunig’s awards and achievements is very, very long, but since the cartoonist says he’s forgotten most of them because they are meaningless, let’s just mention that the National Trust declared him an “Australian living treasure” in 1999, which seems appropriate.

“I wanted to talk about the role of the artist in difficult times,” he said.

“Actually, life is a difficult time. It’s not easy. As well as the honorary doctorates and so on, I’ve also been cancelled quite considerably.

“It’s a big thing to have spent your whole working life offering things to your culture in a quite experimental way, but I think I’ve done it in good faith, made a few mistakes, offended a few people, not deliberately. That’s the nature of political cartooning, but you hurt people without intending to, and so you have to become more thoughtful about your own ideas.”

Although he never moves from the general to the specific, Leunig seems to be referring to last year’s “cancellation” from The Age and Sydney Morning Herald over his “Tank Man” cartoon which they declined to publish.

In it he juxtaposes the famous 1989 photo of the lone man defying the tanks on Tiananmen Square with a cartoon of a lone protestor in front of a loaded syringe. I don’t know if it was anti-vaxxer sentiment driving the cartoon or a more philosophical objection to mandates, but perhaps the bigger question is why ban it?

It was by no means my favourite Leunig but it didn’t offend me as much as the racist undertones of some of the late, great Bill Leak’s work, which we were all given the opportunity to see and judge.

In Peregian Beach last Friday, Leunig softens the mood by placing himself in the context of history.

“[When I started] it was the ‘60s and people were into rocking the boat. Now I think it’s rocking too violently, and I just try to steady it.”

In a moment he will delight us with his skill at “making marks” on paper, but first he offers a poem from his canon:

Artist leave the world of art,

Pack your goodies on a cart,

Duck out through some tiny hole,

Slip away and save your soul.

Leave no footprints, don’t look back,

Take the dark and dirty track.

Cross the border, cross your heart:

Freedom from the world of art.

I love that. The morning after, still pondering other parts of Leunig’s “muddle”, I pick up the Saturday Sydney Morning Herald, as is my habit, and go straight to the back page of the Spectrum section to see if the old man still has it.

I find a beautifully-drawn cartoon of the prime minister kissing a baby, then dropping it and running after being informed that it had been named after Julian Assange.

Cruel, coarse, caustic, hilarious – I laughed like a drain.

Yes, Leunig still has it, in spades.