Imagine Noosa National Park at sunrise, running along the sand tracks with surfboard under your arm, heading for the wonderful waves at Tea-Tree Bay.

Suddenly, right in front of you is a koala tucked into the fork of a scribbly bark gum tree. It’s at head height and looks straight into your eyes.

An unforgettable start to the day. That is the beauty of national parks – wilderness areas that are to preserve and protect the natural environment.

The trouble is they are being loved to death. Apart from the risk of bushfire, the greatest threat to such landscapes is human activity.

National parks are meant to stand for eternity. Every battle to preserve them must be won because once they are gone, they cannot be returned to their natural state.

The natural attraction of Noosa has been retained and even expanded through time by a series of mistakes, failures and persistence.

Mistakes by all sorts of people and organisations, failures by the well-meaning, and success from the persistence of those recognising that this is an area worth fighting for. A special headland and waterways to protect and conserve for generations to come as well as the natural environment.

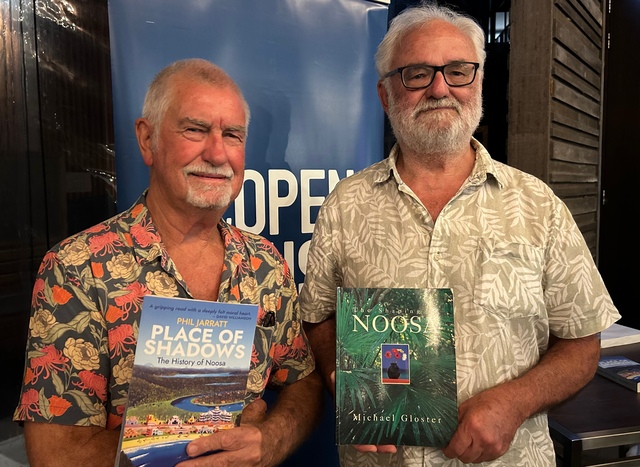

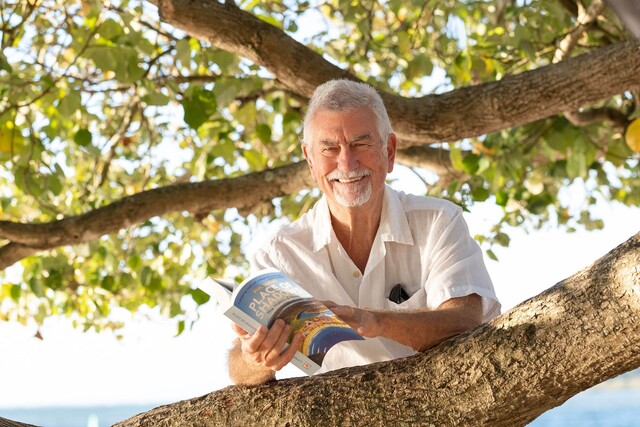

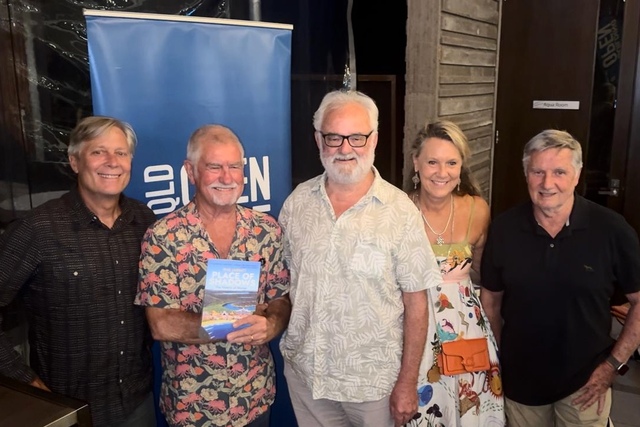

A talk by Noosa-based journalist/author and film-maker Phil Jarratt as part of the Open House program to highlight architecture in the region, focused on how Noosa National Park (NPA) came about.

Phil, who first surfed in Noosa in the 1960s and has been a Noosa resident since 1990, was joined by Dr Michael Gloster of Noosa Parks Association.

As former Noosa Shire councillor and long-standing NPA president, Michael is known for his role in shaping modern Noosa. He has been an architect and driver of national parks from Coolum to Cooloola as a continuous strategy.

Architecture is not simply about good design in buildings but the role it plays in people, places and spaces.

The Noosa National Park came about by mistake in many ways. Yet it is as if it was always meant to be – a reminder of the beauty and magnificence of the natural aspects of the place in which we live.

It is the heart, the soul, the identity of who we are and what is special about this place.

As such it provides a glorious place in the centre of the urban landscape that is modern-day Noosa Heads. A relatively wild space in which to relax and unwind in a world that grows busier day by day.

The majestic headland and bays provide a space in which to reconnect with nature.

While bushfire has always been a threat in Australia, Noosa National Park is threatened more by being loved to death by those who visit it and tread the coastal path.

Yet not everyone living in Noosa or enjoying the park realise it was once threatened by residential development.

It has been the same with the Cooloola section of the park that stretches from the Noosa River, north to Double Island Point and Rainbow Beach.

The creation of the Coolum section from the David Low Way west to Lake Weyba was under continual threat from when the coastal road was built in 1960 between Sunshine Beach and Peregian Beach. The second section from Coolum Beach to Peregian was opened in 1961.

EARLY HISTORY

While Phil Jarratt gave a timeline of the Noosa National Park’s history, he called on Michael Gloster to give an account of the expansion to Cooloola and to Coolum.

“Michael Gloster is more the strategist and activist,” Phil said. “No-one in our community has worked harder over the decades, whether the phones or the meeting rooms to get Noosa’s voice heard, and to help turn a 245-hectare postage stamp park into more than 8000 hectares, creating a crescent of green from Cooloola to Coolum.”

For tens of thousands of years, the traditional custodians, the Kabi Kabi, roamed around what is now Noosa Shire in line with the seasons.

The original Noosa National Park, the Noosa Headland section, was a sacred place of ceremony and an abundant fishing, hunting and gathering ground.

“The evidence of that is the large number of middens that have been discovered over the years,” Phil said, “some of which, hidden in the quiet corners of the park, still exist today.

“The early settlement history of what is now the park can more or less be told in 30-year snippets.

“In 1770 James Cook sailed by and named Double Island Point but made no landfall. In 1801 Matthew Flinders sailed by and reported seeing the smoke of Kabi Kabi campfires on the Cooloola shore, but again, didn’t come in and have a look.

“Another 30 years later a run of escapees from the recently-established Moreton Bay penal settlement, collectively known as the Wild White Men, decided to chance their luck fishing with the Kabis on the Noosa River rather than suffering the indignities of prison life.

“About a decade later, a couple of the escapees from prison were discovered by Andrew Petrie, a Scottish-born architect, builder and explorer, who brought them back to the Brisbane River.

By the late 1860s gold had been discovered at Gympie, and the timber industry started at Mill Point on the upper reaches of the Noosa River to supply the needs of the gold diggers.

“A track had been cut through the bush to enable the Cobb and Co coach to get to the goldfields from the river port of Tewantin, where a new town had been surveyed.

“The name came from a Kabi Kabi word meaning place of dead logs, referring to the logs floated down the river for shipping to Brisbane.”

But what of little Noosa Heads?

Phil said the arrival in 1872 of the Reverend Edward Fuller and his devout wife Mary was a major step in Noosa’s history even though it was shrouded in failure.

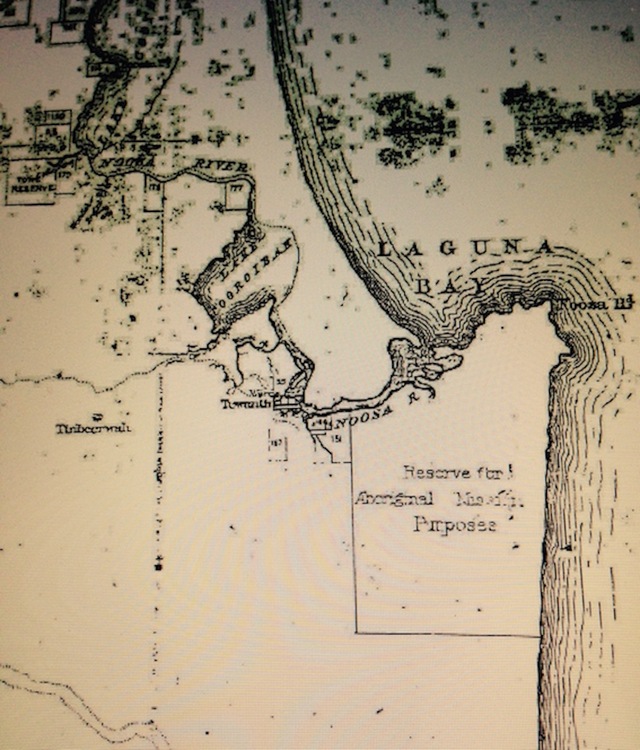

“Rev Fuller’s great gift to Noosa was his request, through the Aboriginal Missionary Society, for a plot of land on the banks of Weyba Creek to house a humble home, a mission station and hopefully a Kabi Kabi camp.

“In July 1872, the Queensland Lands Department gazetted a grant of 10,000 acres of recently surveyed land, encompassing all of what we now know as the Headland section of Noosa National Park, the sites of the villages of Noosa Heads and Noosa Junction, and a fair chunk of Sunshine Beach.

“The squatters, of who there were not many, were outraged. However, the Noosa Aboriginal Reserve and Mission was a flop – the Kabi Kabi preferring their existing camps along the river settlements.

“Rev Fuller made a timely exit and the reserve was cancelled in 1878, when parts of it were opened for selection. Another 1000 acres was reserved for the creation of a township, and much of that is what now forms the Headland section of the park.

“By the early 1900s most of the Kabi Kabi population had been forcibly resettled 150km inland on another mission called Barambah, now named Cherbourg.

“Meanwhile the village of Noosa Heads had been taking shape around the Hastings Street precinct, with a few shops and a couple of accommodation houses for the almost non-existent tourists.”

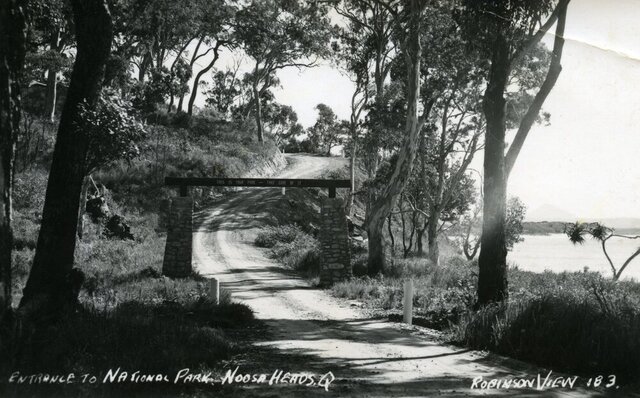

Noosa’s modern history started with the declaration of a land-locked Noosa National Park, just weeks before the start of World War Two.

It would be another decade until 1949 before the park was officially opened by Sir John Lavarack, the first Australian-born Governor of Queensland.

In 1959 it was all about new arrivals in Noosa, and that included Dr Arthur Harrold, his wife Marjorie and their two sons.

Arthur was a GP who apparently had no time for niceties and he discovered the “big lie” about the Noosa National Park.

“The lie was that the entire coastal track, the most popular part of the park, was not actually national park.

“From the gates of the park to North Sunshine Beach, there was a clifftop corridor of magnificent ocean views which could provide motor access to some crown land, a water reserve and, most importantly, a freehold estate behind Paradise Cave held by developer TM Burke.

“Arthur Harrold didn’t hold back. He would take a map of the park boundaries on his coastal track walks and bail up other walkers and say, ‘Isn’t this magnificent? And do you

realise that this is not part of the park and could be turned into a coast road?’

“By 1962, Arthur and Marjorie, with like-minded friends like Max Walker, Guy L’Estrange and Jim and Cecily Fearnley, had enough support to found the Noosa Parks Development Association. “They were clever, committed and fearless, and they got to work on expanding the park, first by getting the coastal track included, and then working through the rest of the dominos – the crown land in 1967, the water reserve in ’72, and finally the TM Burke estate in 1984.”

At the same time the Noosa Parks Association was looking to expand the green belt wherever it could, even across the river in Cooloola, where they found an unexpected ally in Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

“When the Parks Association was founded in 1962, just one percent of Noosa Shire was National Park. By 1982 it was more than 10 percent, a lot of that being Cooloola.

“Today it’s 45 percent, making Noosa undeniably ‘Different by nature.’

“How another 35 percent of green was added over the past four decades is a very big story in itself, and there’s no one better to tell it than Dr Michael Gloster.”

THE NEXT STEPS

Conserving the headland section of the Noosa National Park took a huge effort, Michael Gloster said, but there was a vital need to expand both north to Cooloola, and south to Coolum.

Michael explained that how in the 1980s, together with shire chairman Noel Playford and other councillors, they came up with a way of extending the national park to Coolum.

“We needed a new strategy. The huge hold-up for a generation was the strip from Noosa Headland to Coolum being controlled by TM Burke.

“They had been given a development lease for the entire coastal strip in return for building a road there.

“The Department of Main Roads had planned to have a future arterial road running along the shoreline of Lake Weyba, and TM Burke had expected to develop all of that land.”

Noosa Shire Council had asked TM Burke to prepare a master plan with a capacity of 100,000 to live there, Michael said.

The first step was to get the motorway rerouted to the west of Lake Weyba to where it is now – that took five years just to achieve.

The next step was to get that land between the existing communities to Lake Weyba included in the national park.

The late Cr Heather Melrose was relentless in studying archives, researching documents and she finally came up with the needle in the haystack, Michael said.

The development lease had never been defined to the western side.

It was then Premier Wayne Goss who agreed to the combining of Noosa Shire Council and State Government land in that parcel.

Yet it didn’t include the Marcus high dunes, that had resort development slated for it.

There was even a Big Rocket theme park proposed, together with an Emu Swamp residential development – inland from southern Peregian.

Since then the Noosa National Park has been extended to Stumers Creek, in association with the then Maroochy Shire, and subsequently got continuity behind Peregian Springs to Tewantin National Park.

It involved hundreds of NPA volunteers and thousands of Noosa residents, Michael said.

There was luck in the story but the inspiration provided for council staff in the 1980s by the new councillors, and the persistence they showed meant they were able to move what was thought to be the immovable objects of bureaucracy.

PEOPLE, PLACES AND SPACES

Besides bushfire, sand mining and residential development, the greatest threat to the national park, is a battle of the minds, Phil Jarratt said.

The pressures that have come over the past 30 odd years as to access to the national parks, whether it be a surfer or a jogger a wind surfer or jet ski, shows that these areas are being loved to death.

“It’s something we have to learn to live with. We don’t think politics, we think what’s good for the country,” Phil Jarratt said.

The question is, how do we ensure there are spaces – not just manicured recreational areas but wilderness such as Noosa National Park where fragile landscapes can be protected?

Michael Gloster tried to put it into some sort of perspective in that until about 20 years ago, national parks had certain behaviours that were allowed and others weren’t – but that approach changed.

While we recognise these are important areas to conserve, we have to understand there needs to be some recreational uses.

What is profoundly happening is a certain percentage of people have a sense of entitlement that is downright rude – whether it be at the car park, what they bring into the park or how they utilise it.

The spaces that were once considered worth conserving, such as the North Shore, are now seeing behaviour happening more and more.

“The concept of leaving only footprints is disappearing before our eyes.”

SOMETHING WORTH PRESERVING

To protect the park so it can be enjoyed now and in the future:

Everything in the park – living or dead – is protected. Do not take or interfere with plants, animals, soil or rocks.

Leave pets at home; they are prohibited in the national park. Pets can frighten or kill wildlife, annoy other visitors or become lost.

Take all rubbish out of the park for appropriate disposal. Never bury or leave rubbish in the park.

Stay on tracks. Do not cut corners or create new tracks as this causes erosion.

To see more information about the Open House Sunshine Coast program that is held Saturday and Sunday, October 19-20: www.sunshinecoastopenhouse.com.au/