Last week Unitywater joined a growing number of organisations and companies offering employees the opportunity to swap the 26 January Australia Day public holiday for another day in lieu.

It’s hard to know what it says about our country when a significant and growing number of us are ashamed to celebrate our national day, but Unitywater chief executive officer Anna Jackson said: “There are many things to celebrate about being Australian, however Unitywater recognises that 26 January doesn’t represent an inclusive and unifying day for everyone. Giving our people a choice is another way to demonstrate our commitment to reconciliation and provides a more respectful choice for everyone and for our First Nations team members.”

While people who feel uneasy about celebrating the arrival in Sydney Cove of 11 shiploads of British soldiers and convicts are not necessarily swept up in the rhetoric of the Invasion Day protesters, they may well be just as confused as the myriad people who have been debating this issue every January, in the media, the pub and around countless beachside and backyard barbeques since 1994, when Prime Minister Paul Keating, fresh from the triumph of Mabo, confusingly shifted the holiday from the last weekend of January to the specific date of the 26th, aligning it with the events of 1788 just as we were beginning to embrace the concept of Native Title.

Clearly Keating didn’t see it as a celebration of an invasion.

But some historians and activists certainly had, dating back more than half a century to the late 1930s.

The Oxford Dictionary defines invasion as “the act of an army entering another country by force in order to take control of it” and, strictly speaking, that’s not what happened on 26 January 1788.

It’s interesting to look back at what actually happened on that date, and to go back 18 years earlier and ponder whether any kind of invasion could be said to have taken place in 1770.

Having observed the Transit of Venus in the South Pacific, Lieutenant James Cook and a crew of 94 aboard the brig HMB Endeavour sailed south to New Zealand then west to what they assumed was the uncharted Great South Land and followed its coastline north from April to August 1770, before naming it New South Wales and proclaiming it for His Majesty King George III by hoisting the English colours in the sand at a cay just beyond the tip of Cape York (given the name Possession Island) on 22 August and firing off a few volleys before departing for home.

Despite the fact that Cook and his crew had not only seen inhabitants in every place they dropped anchor, but had land parties engage with them and on at least two occasions open fire on them, back in England, Cook and his botanist Joseph Banks informed the government and the Crown that the possession had been made under the then-acceptable doctrine of terra nullius, meaning that no one lived there.

But terra nullius was not officially proclaimed, with the benefit of hindsight, for another 65 years, by which time the people who thought that living there for more than 60,000 years gave them some sort of rights of possession were mounting a rearguard action that become known as the Frontier Wars.

Meanwhile, in the 1780s, the British penal system was bursting at the seams since they’d lost their convict dumping grounds in Africa and America.

Although Cook was long dead, murdered by Hawaiians who apparently took issue with his definition of terra nullius, his vision of Botany Bay as the capital of the colony of New South Wales seemed fit for purpose and, in due course, the fleet of criminals and their keepers, under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, sailed into Botany Bay on 19 and 20 January 1788.

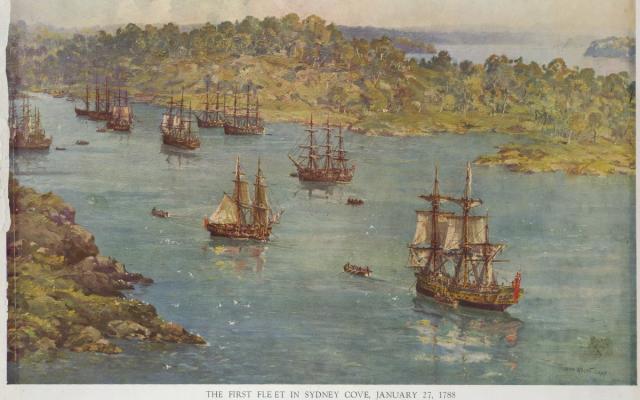

It took Phillip just a couple of days of further exploration to realise that there were better options for a settlement than scrubby Botany Bay, and on 25 January he sailed the Supply north to what would be named Sydney Cove, followed overnight by the rest of the fleet.

As the master of historic reimagining, Manning Clark wrote in the first of his six-volume History of Australia: “In the afternoon [of 26], the officers and marines having landed, the flag was hoisted on shore, while four glasses of porter were drunk to the health of their Majesties and the Prince of Wales, with success to the colony. Then the marines fired a feu de joie. The whole group gave three cheers… Such was the display to enliven spirits… on the day European society conducted its first ceremony in Australia.”

Clark did not record the reactions of the inhabitants who weren’t officially there, looking on hidden behind the tree-line around the cove.

Two hundred years later, just after midnight on 26 January, I waited with a photographer on a wharf in Botany Bay, then boarded a tall ship called Our Svanen to join the First Fleet Re-enactment as it sailed into Sydney Harbour from first light.

The Bicentennial celebration was a riotous, joyful affair, pretty much free of controversy or protest. There were no cheesy costume black/white handshakes in front of the Opera House, or exchanges of boomerangs for rum, but I doubt that it could have occurred 10 years later.

Public sentiment was on the move. It just didn’t know yet where it was going.

First Nations’ philosopher Noel Pearson has advocated for a two-day commemoration for about a decade now, reasoning: “For Indigenous Australians and the many other Australians who empathise with the view that 26 January is ‘dancing on our ancestors’ graves’, 25 January should be a most important date. For on the eve of 26 January the entire east coast was held under the ancient sovereignty of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes, the First Nations of Australia. This sovereignty existed over the entire continent and its islands.

“In retrospect, this 48-hour period is the most turbulent in the continent’s history, and for good reason. It is controversial, and will remain so for as long as we cannot find a way to unite around its meaning and reconcile, because profound things happened in those 48 hours. Sovereign possession extending back 65 millennia existed one day, and then a new sovereign possession was unilaterally asserted the next day. The new sovereignty treated the ancient sovereignty as if it never existed.

“There lies the pain and deeply held injustice. There lies the reason and imperative for recognition.”

Personally, I’m not sold on a black Australia Day followed by a white one, but Pearson hits the nail on the head when he explains our Australian story in these terms: “The ancient Indigenous heritage which is its foundation, the British institutions built upon it, and the adorning gift of multicultural migration”.

Let’s choose a day – any day but 26 January – and celebrate all of that, while remembering the injustices and the sacrifices along the way.