It’s funny how councils work in cycles with history sometimes repeating itself and frequently throwing up quirks and curiosities.

For example. about 40 years ago, when he first bought riverfront property on the Noosa North Shore, unsuccessful 2024 mayoral candidate Nick Hluzsko kept finding rusty fragments of machinery on his block, and a little research revealed that a timber mill had once been there, along with the home of the mill manager James Duke, who was also Noosa Shire’s first chairman.

Had the scattered remains of the mill, the Duke home and other parts of the forgotten village of Colloy conjured up the spirit of old Jim Duke and got Nick across the line this year, we’d probably still be walking around humming the theme from Twilight Zone. That didn’t happen but we are in the thick of the 1910 anniversary season – the proclamation calling the election was made on 31 March with the election taking place, following a three-week campaign (if you could call it that), at the tiny Federal Hall in Cooran on 22 April – so it’s timely, and possibly even educational, to look at the parallels between then and now.

The first parallel with 1910 is with Noosa’s 2014 re-emergence from six troubled years of amalgamation into the Sunshine Coast “super council”, but if the de-amalgamationists then thought they were doing it tough, their situation had nothing on more than 30 years of uncaring and unfunded governance from afar that Noosa had suffered prior to becoming its own shire. Since the colonial government of Queensland in 1879 established 74 “divisional boards” to decentralise governance across the new areas of settlement, Noosa’s administration by the Gympie-based Widgee Divisional Board had been a constant bone of contention, mainly because the Widgee Board never had any money to fund essentials like road maintenance.

Following the disintegration of the Alexandra Bridge over Weyba Creek (funded by a thousand-pound loan from a London bank) just a handful of years after its 1886 construction, Noosa Heads had remained accessible only by boat. To the movers and shakers of Noosa, the borer-eaten, burnt out stumps from the bridge had become a symbol of all that was rotten in the division of Widgee. But if Widgee had no money in 1879, it had even less by the new century, after almost a decade of recession. As Noosa grew, so did the demands for expenditure, and the rumblings of discontent.

Talk of separating from Widgee, by now a shire, was a constant around the gentlemen’s lounges of Tewantin, particularly at Dan Martin’s Tewantin Hotel, and within days of hosting pioneer explorer and settler Walter Hay’s wake in 1907, Martin, the Noosa representative on the Widgee board since 1895, found himself voted off, presumably in an attempt to quieten the separatists. It didn’t work. In November 1909 the Home Secretary’s Office served notice on the Widgee Shire Council that it intended to form the Shire of Noosa.

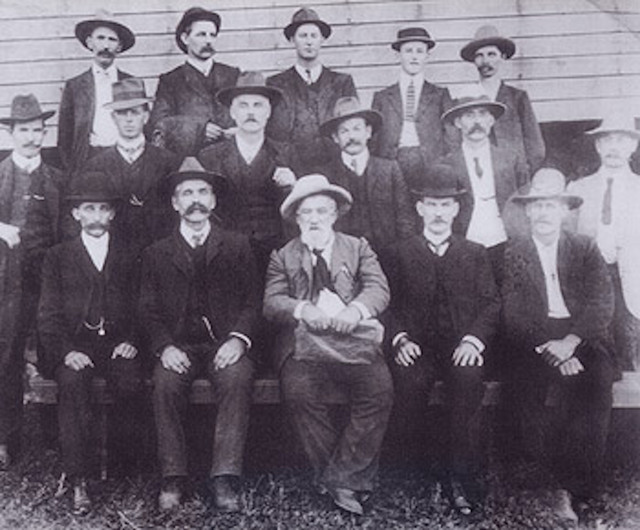

By March there were 15 nominations for the nine councillors required, all male of course, and with fewer than 700 ratepayers eligible to vote, the results were fast and decisive. At the first statutory meeting of the Noosa Shire Council on 11 May (also held at the Federal Hall, to comply with the proclamation) the elected councillors more or less drafted James Duke as their founding chairman.

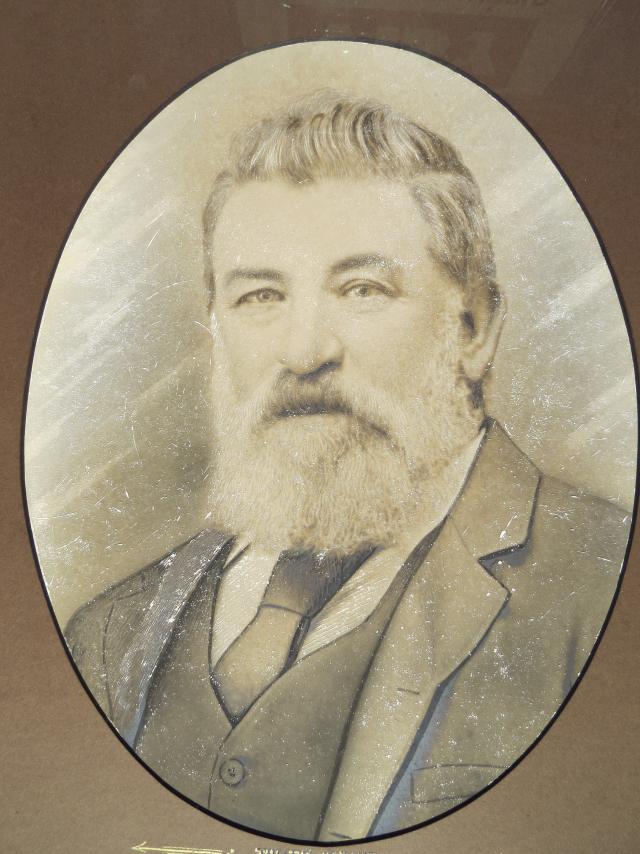

Born in Liverpool, England, in 1841, Duke had worked his passage to Australia in 1863 as an able seaman on the Everton, but the ship was caught in a gale and wrecked on Moreton Island. Nothing about Duke’s subsequent life in what was to become Noosa Shire ever quite matched the excitement of his arrival, but he rose to the position of general manager at timber giant Dath Henderson and Co, owned the first building in Cooroy, raised a family in Tewantin and Colloy, and developed considerable landholdings in what is now known as Doonan.

When elected chairman he was 69 years old (call that 80-plus in today’s life spans), and he was seen as a caretaker with a safe pair of hands for the short time it would take to get the council on track. Noel Playford was approximately the same age when he was elected mayor of the reborn Noosa Shire in 2014, and the understanding was similar – that the crusader for empathetic town planning of the ‘90s was now a safe pair of hands for the shortened term of two years.

But Jim Duke was no Noel Playford. He was overwhelmed from the start, despite his management background.

The first major business of the new council was to choose the site for a permanent council chambers. Cooran’s term as the seat of the shire was always meant to be temporary, but at the first council meeting its residents made sure it was one of four centres that vied for the permanent honour. Cooran, Tewantin, Cooroy and Pomona all nominated and Cooroy won the final vote and started hiring contractors and buying timber from the Cootharaba mill to build the shire chambers.

But within a few months the decision had caused uproar throughout Noosa, with representatives of the other divisions presenting a petition to the Home Secretary demanding that Pomona be selected because it was more central. In a referendum on 11 March 1911, Pomona pipped Cooroy by just 11 votes. As builders were sacked and timber sent back to the mills, Noosa Shire moved onto the more pressing but less entertaining business of the day. The Shire was broke.

Discussing the issue of a new bridge for Cooran, shire clerk Edgar Edwards (who held the gig until 1946) did not hold back: “The Financial aspect of this matter is enough to turn all the Councillors grey. [Most of them already were.] The Council have nothing, absolutely nothing, if I want a piece of India rubber in the Office I have to go out and buy it, there is not a pick or a shovel belonging to them, there is all the initial expense of getting things, there is the problem of more miles of bad roads or worse than bad roads, no roads, to face, than I care to think of.”

This was a bridge too far, a road too pot-holed for old Jim Duke, who handed the chairman’s robes to Frances Conroy, a sawyer who lived in a humpy near Cooran with neither power nor running water. He served three years in the chair and proved to be capable and decisive. Frank Conroy was more or less a regenerative-farming environmentalist a century before his time, which leads us to a final parallel with now.

Our new mayor is also a renaissance man named Frank who certainly doesn’t live in a humpy but plays guitar and sings, treads the boards with great distinction, runs marathons, writes plays and has even, in the distant past, risked his reputation as a provincial journalist with opinions. We who also toil in this troubled field, wish him well as he leads us back to the future.